Recapitulation on Counting

In the previous two posts, I introduced ideas related to counting. In Learning to Count we introduced the idea of combinatorial arguments, which allowed us to gain some insight on the process of selection. In Abjuring Double Counting we saw the recursive process used to ensure that, when we count members of sets that have common elements, we neither omit them nor double count them. I had signed off last time with the promise that we will look at something I called ‘derangements’. Of course, the dictionary states that derangement is “the state of being completely unable to think clearly or behave in a controlled way, especially because of mental illness.” Quite obviously, this is not what I’m referring to! So what am I referring to?

Understanding Derangements

In mathematics, specifically in the area of combinatorics, a derangement is a permutation or arrangement in which no item occupies a position it previously occupied. This, I guess, is still a little vague. So let us consider a couple of examples.

Suppose we have a set of n letters that are in the mailperson’s bag. Obviously, each of these letters has an address on the envelop. However, if the mailperson delivers them such that no letter is delivered to the address on its envelop, then we have a derangement.

Or suppose n patrons of a restaurant check their coats in with the maître d’. On their way out the patrons collect the coats, but none of them receives their own coats. In that case, we have a derangement.

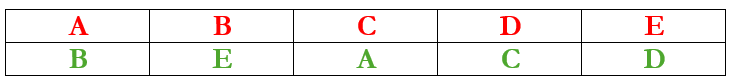

We could visualize a derangement as below

Here, we have five items (A, B, C, D, and E). However, none of the items in green matches the corresponding item in red. Using the ordering ABCDE, the above derangement is BEACD. In what follows, I will use red lettering to indicate an item that is not deranged, that is, an item that is placed where it belongs. And I will use green lettering to indicate an item that is deranged, that is, an item that is not placed where it belongs.

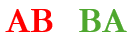

We can begin counting the number of possible derangements with small set sizes. For example, with 2 items, A and B, there are 2 permutations:

As shown above, there is only one derangement.

If we increase the set size to 3 items, A, B, and C, there will be 6 permutations:

As can be seen above, there are only 2 full derangements.

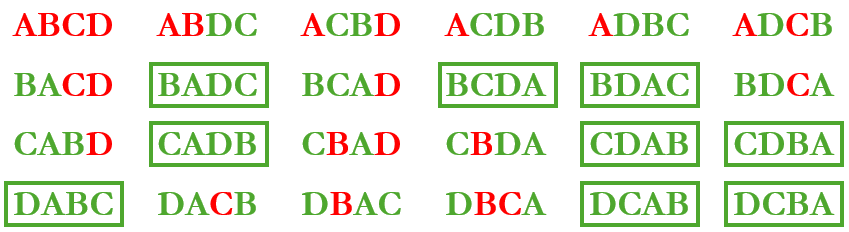

We can increase the set size to 4 items, A, B, C, and D, to get 24 permutations:

As seen above, there are 9 full derangements, indicated in green boxes.

Now, with a set of 5 items, we will have 5! or 120 different permutations. I don’t know about you, but I’m disinclined to even write out all these permutations, let alone scrutinize each to determine which items are deranged, then determine which permutations are indeed full derangements, and then to count the number of full derangements. If you have way too much time on hand for mind numbing tasks, please feel free to step away and undertake this not just for a set of 5 items, but a set of (say) 10 items, for which you can write down and scrutinize all the 3,628,800 permutations!

You see, the factorial function grows at an alarming rate. What might even be manageable for a set of 5 items, with 120 permutations, becomes an onerous task for a set that is just double the size, with millions of permutations. Hence, there must be a better way of determining the number of derangements given the size of the set. And, thankfully, there is!

We will proceed along two routes, both yielding the same result. But because the paths are different, we will discover different insights on the process. The first route we will adopt will use the inclusion-exclusion principle that we saw in the previous post. The second route will use a recursive formula.

Derangements using the Inclusion-Exclusion Principle

Given n items, there are n! different ways of permuting them. Out of these n! ways, there are (n-1)! arrangements in which item 1 is fixed in its own position. These (n-1)! arrangements include arrangements in which some other items may also be in their own positions. Similarly, there are (n-1)! arrangements in which item 2 is fixed in its own position. Again, these (n-1)! arrangements include arrangements in which some other items may also be in their own positions.

Of course, for each of the n items there are (n-1)! arrangements in which that item is fixed in its own position. Since there are n items in all, we are looking at

arrangements in which at least 1 item is fixed in its own position.

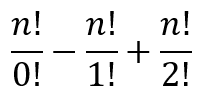

So now we have in consideration the initial n! less the arrangements in which 1 item is fixed. Hence under consideration now are

arrangements. It is clear, however, that there has been double counting for arrangements in which any pairs of items are both in their own positions. Hence, per the inclusion-exclusion principle, we now need to add all the arrangements in which pairs of items are fixed in their positions.

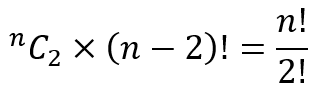

Suppose items 1 and 2 are fixed. There are (n-2)! such arrangements and these arrangements include arrangements in which items other than 1 and 2 are also fixed in their positions. There are, of course nC2 different pairs of items and for each such pair there will be (n-2)! arrangements in which the items in the pair are fixed in their positions. So we are looking at

arrangements in which 2 or more items are fixed in their positions. As mentioned, due to double counting, these need to be added back. After this adjustment we will be considering

arrangements. Of course, now we have overcompensated for the arrangements in which 3 items are fixed in their positions. We will need to subtract these.

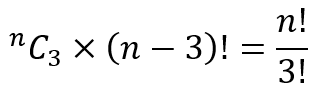

Now supposed items 1, 2, and 3 are fixed in their positions. There are (n-3)! such arrangements and these will include arrangements in which items other than 1, 2, and 3 are also fixed in tier positions. There are nC3 different triplets of items and for each such triplet there will be (n-3)! arrangements in which the items of that triplet are fixed in their positions. So we are looking at

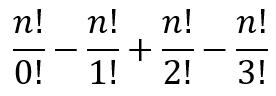

These arrangements will need to be subtracted from the running total that we have, yielding

Continuing in this manner, we can see that the final number of derangements after all the appropriate inclusion-exclusion will be

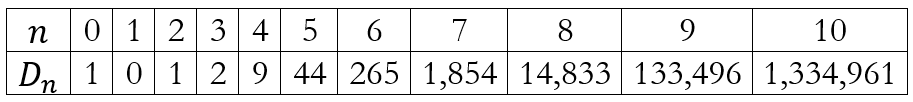

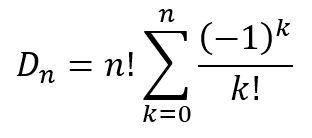

This can be written in a more compact form as

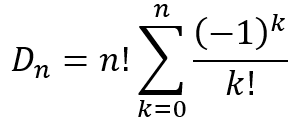

Using this formula we obtain the table below for values of n up to 10.

Derangements using a Recursive Formula

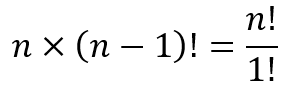

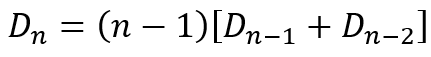

The second method for counting derangements is by using a recursive formula. We will first derive the recursive formula and then modify to demonstrate that it is equivalent to the one we just derived. Once again, we start with a set of n items. Now consider item 1. In order for us to end with a derangement, this item must be placed in one of positions 2 to n. Hence, there are n-1 ways of placing item 1. Since the number of derangements is a whole number, we can conclude that

where X is another whole number that we have to determine. Till now, we have placed 1 of the n items in a position other than its own.

Now let us focus on the kth item since it has been dislodged by item 1. We can either place it in position 1 or in one of the remaining n-2 positions. It we place the kth item in position 1, then we still have to derange the remaining n-2 items, which can be done in Dn-2 ways. If we do not place the kth item in position 1, then there are still n-1 items, including the kth item, that have to be deranged, which can be done in Dn-1 ways. Since the kth item must go either in position 1 or in one of the other n-2 positions, the two cases are mutually exclusive and exhaustive. Hence, we can conclude that

The expression in the square brackets should remind us of the binomial identity

You will recall from two posts back that we had considered the matter of selecting r out of n+1 items and we focused on one item, concluding that the selection either does not contain this item, represented by the first term on the left, or does contain this item, represented by the second term on the left.

While deriving the recursive equation

we used the same idea of focusing on one item and deciding whether it still needs to be deranged, represented by the first term in the square brackets, or has already been deranged, represented by the second term.

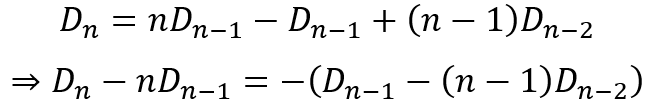

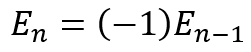

This can be expanded and rearranged as follows:

Supposed we designate

Then we can see that the earlier equation can be written as

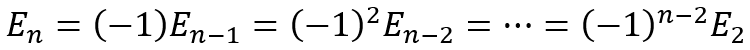

Using this recursively we get

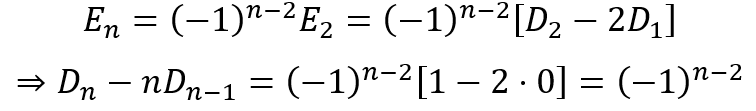

Substituting in terms of the derangement values we get

This can be rearranged as

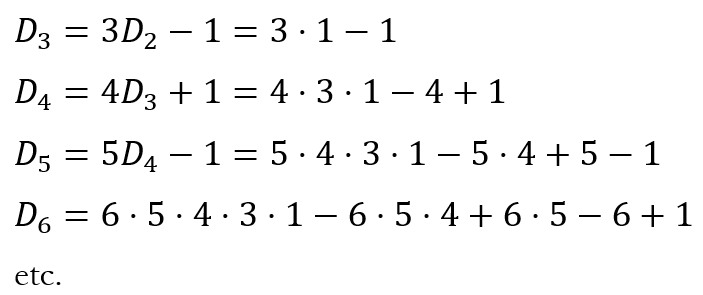

We can now substitute values for n to obtain the corresponding expressions for Dn. This will give us

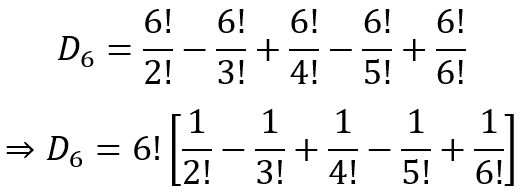

Considering the expression for D6, we can see that it can be rewritten as

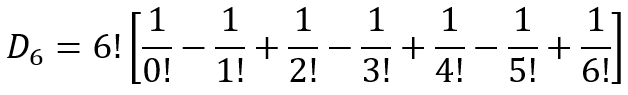

And since 0!=1!=1, we can further write it as

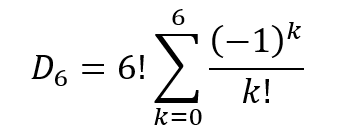

Using sigma notation, this can be written as

This can be generalized to

which is exactly the same expression we obtained earlier using the inclusion-exclusion principle.

Derangements and the Inclusion-Exclusion Principle

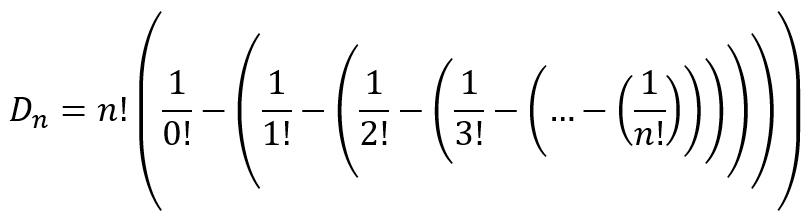

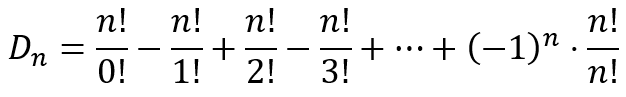

The formula for derangements can be further written as

where the nested parentheses show how the inclusion-exclusion principle works, much like the matryoshka dolls in the image at the start of this post. What this formula tells us it that we can calculate the number of derangements by considering the total number of permutations and subtracting the cases where at least 1 item is fixed, subtracting the cases where at least 2 items are fixed, subtracting the cases where at least 3 items are fixed, and so on. Due to the fact that (-1)n oscillates between 1 and -1, the nested parentheses accomplish the same final result as do the alternating signs in the original formula we obtained, namely

Why Derangements aren’t Deranged

So far the discussion has been reasonably theoretical. And you might wonder if there is any reason for understanding derangements beyond the curiosity of mathematicians. I’ve tried to determine how the idea of derangements came about but have not been able to land on a definitive answer. It is quite likely, as in many cases in mathematics, that some mathematician just toyed with the idea and that the idea later found applications. So what are some of these applications?

In the workplace, if you wish to ensure everyone in a team has the opportunity to be responsible for every process, the idea of derangements is essential. In fact, if the team leader intentionally uses the idea of derangements, he/she could reallocate in a more efficient manner than just reassigning and checking if he/she has obtained a full derangement.

In coding, the idea of derangements is used to check for coding errors. In stochastic processes, derangements are used to determine the entropy of a system. In chemistry, the idea of derangements are used in the study of isomers, the number of which increases rapidly especially for compounds with long carbon chains. In graph theory, the idea of derangements can be used to determine unique walks or paths in a graph. In optimization, derangements are used in situations similar to the traveling salesman problem or the assignment problem.

In other words, while it is likely that the idea of derangements began with the toying of a mathematician, it has a wide range of applications today. But what surprises me in something that I am going to deal with in the next post. It is a result that is shocking to say the least and downright mysterious. Whatever could it be? And with that cliff hanger, I bid you au revoir for a week.

Leave a comment