The Growing Frustration

It’s frustrating. Yes, you heard me right. It’s frustrating. You may be wondering why I am saying this and in what context. So here goes. Just the other day, I was looking up some perspectives on a mathematics discussion forum. Quite naturally, there were many mathematics teachers in the forum. And quite naturally there was some discussion about questions asked by students.

As a mathematics teacher, I find these questions quite illuminating. In fact, this is one of the reasons I love being a teacher. You never know what would spark the interest of some student enough to formulate a question. So even though what I teach might be much the same from year to year, because who I teach changes, it is never boring. Indeed, even when you teach the same group of students, as I did from 2016 to 2018 and then 2020 to 2023, you can see their questions change as they themselves mature and change.

But it’s time to stop this nostalgic reverie and return to my frustration!

Case I: Equivalent Fractions

One question on the forum was asked by the teacher of a student in elementary school. I presume this is between Grade 1 and Grade 5. The student was learning fractions. When they came to the concept of equivalent fractions, the student asked the teacher what was different between the fractions 6/8 and 3/4. The teacher asked the question on the forum, requesting advice on how to respond to the student.

The poor teacher! The backlash she faced was unconscionable. So many of her fellow mathematics teachers pounced on her to tell her not just that both fractions are the same but that any mathematics teacher worth his/her salt should know this. Some questioned her competence to teach the subject. I commented, taking her side, and posted a link to a previous post in which I demonstrate that equivalent fractions might have the same value but do not contain the same information.

I faced the same issue in a recent class. A student asked me what the difference between various equivalent fractions was. That this student is currently in Grade 12 and is a reasonably astute student is an indictment against all his mathematics teachers.

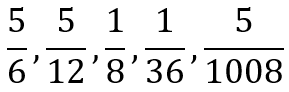

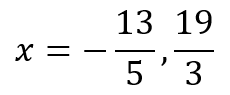

Anyway, the question arose when, in answer to a problem, the student gave me the following numbers:

The student had calculated accurately and the numerical values of each of these fractions was spot on. However, I told him that, by reducing the fractions to their lowest forms, he had lost something crucial. It was then that he asked me the question about equivalent fractions.

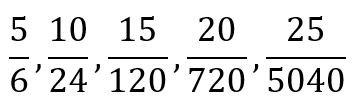

So I gave him another set of fractions:

I asked him what links this set of fractions. He struggled, unsuccessfully, for a few minutes. Then I told him that I had generated this set of fractions in a very similar way to the one with which he had generated the first set. I gave him a few more minutes to try his luck, to no avail.

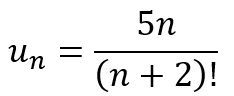

What was it that gave rise to these two sets of numbers? There is clearly no discernible pattern in either of the sets and they may seem to be just some random fractions generated by an addled mind. However, what if I told you that the first set, before reducing to equivalent fractions, was

Right away, you will recognize that there is a pattern. The numerator is composed of multiples of 5, while the denominator is composed of factorials, starting with the factorial of 3. If I asked you to give me a formula for generating the terms, you will quickly be able to tell me:

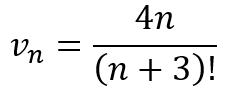

Similarly, if, for the second set of numbers, I gave you

you will equally quickly be able to tell me

You see, while the numbers in the first set and third set have the same corresponding values (and similarly with the second and fourth sets), something is lost by reducing the fractions to their lowest terms. And with this loss, we are rendered incapable of generating further terms in the sequence because the process of reducing the fractions destroys the pattern.

Case II: Quadratic Expressions

This shows up in other places too. For example, one of the students I am currently tutoring is studying quadratics at school. Now this student is exceptionally bright. When I was concluding a class, I asked her to think about the difference between

and

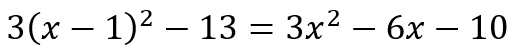

For those unfamiliar with the above, let me give an example.

The above is an example of the fact that any quadratic expression of the form

can be expressed in the form

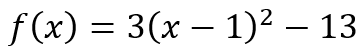

But what was the point of the re-expression? Why should we bother to do it? In the next class I asked my student if she had given this some thought. She said she had but that she could not figure out in what way

is different from

Since we had just started learning about quadratics, I did not fault her for not being able to answer the question. After all, that’s what learning is. But she told me that she had asked her teacher about the difference. And her teacher had told her that there was no difference because

I’m glad the class was online. Otherwise, my student would have felt my fury palpably. It is likely that she did sense it even over our Zoom call! The statement of the teacher is absolute rot and betrays a failure to look below the surface. For, while both expressions are indeed equivalent, the expression on the right tells me that this quadratic expression, if plotted as a function of x, has a vertex at the point (1, -13). You may wonder, “What’s the big deal? So what if the expression on the left gives me the coordinates of the vertex? I could do a few steps of algebra and get it.” Absolutely true.

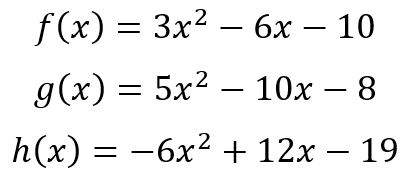

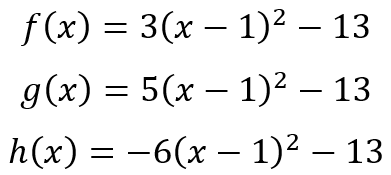

However, if you were given the functions

you would not know that they all have the same vertex. However, if they were written as

the fact that the vertices are at (1, -13) is indisputable. But more than that, the second set of equations also tell us, from the signs on the coefficients 3 and -13, 5 and -13, and -6 and -13, that f(x) = 0 and g(x) = 0 will have real roots, while h(x) = 0 will only have complex roots.

Case III: Theory of Equations

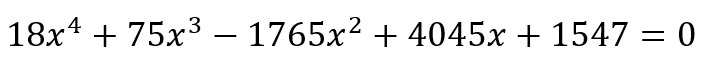

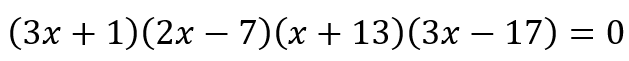

The same kind of issue shows up when we attempt to solve equations in general. Suppose, for example, you are asked to solve the equation

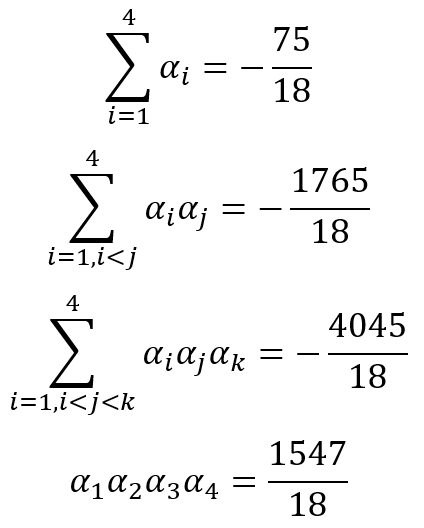

How would you proceed? Of course, you can use some general results from the theory of equations and conclude

But after this, what? Every student who has fumbled with these results will know that, if you try to solve these equations by some standard methods like elimination or substitution, you will revert to the original equation. So while the above four results give some valuable insights about sums and products of the roots of the equation, they do not bring us any closer to actually solving the equation.

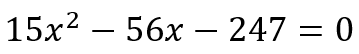

When it comes to just simple quadratic equations, of course, the above method is powerful. After all, suppose we are given the equation

A little back of the napkin calculations will tell me that I need to find two numbers α and β such that

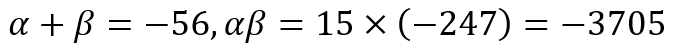

With a little effort, I can determine that the divisors of 3705 are 1, 3, 5, 13, 15, 19, 39, 57, 65, 95, 195, 247, 285, 741, 1235, and 3705. I can place them in pairs as follows: (1, 3705), (3, 1235), (5, 741), (13, 285), (15, 247), (19, 195), (39, 95), and (57, 65), where the numbers in each pair gives the product of 3705. Now since I have -3705 and not 3705, I need two numbers of opposite signs. And since I have -56 and not 56, I need the number with the larger magnitude to be negative. This gives the pair of numbers to be 39 and -95. Now we can proceed to split the middle term and factorize, giving

This allows us to see that we have the product of two numbers equalling zero, which must mean that either of the two numbers is zero. This allows us to conclude

While this method is relatively simple and straightforward in the case of quadratics, there is absolutely no way to use it when it comes to any generic polynomial equation of higher degree, like the quartic equation we saw earlier.

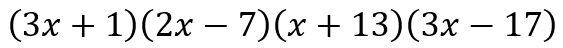

However, the actual way of solving the quadratic, by having a product equal to zero, should allow us to see that, if we had a quartic equation of similar form, we would be able to solve it. Indeed, the earlier quartic equation can be written as

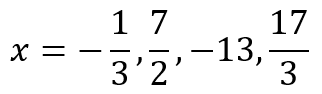

This will allow us to conclude that

In other words, though it is almost child’s play for a student in grade 9 or above to show that

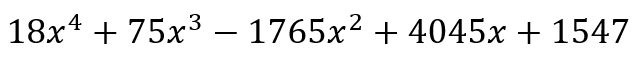

can be expanded to give

it would take even a skilled mathematician quite a few iterations of trial and error before she was able to solve

However, most high school students and perhaps even some middle school students would be able to solve

It is, therefore, quite frustrating when students come to me in Grade 11 and tell me that their teachers either found no difference between the expanded forms of expressions and the factorized forms or that they actually preferred the expanded form. Granted that the parentheses seem intrusive at times, one person may certainly prefer the visual appeal of the expanded form to the factorized form. However, when it is clear that the expanded form is difficult, if not impossible, to solve, this would be like preferring opacity to lucidity.

Case IV: Permutations and Combinations

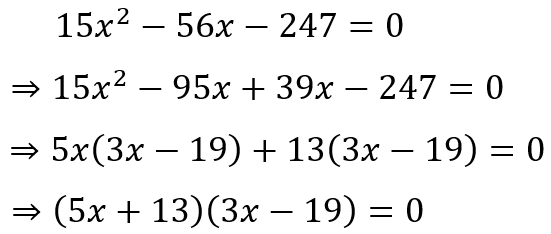

I attribute this unfortunate preference to the noose like grip that textbook publishers and calculator manufacturers have on the global high school examination boards and schools. This fourth case, should highlight this point well. Suppose we were faced with the following problem. In how many ways can a committee of 7 people and another of 8 people be chosen out of 25 people such that 2 members of each committee are to be designated as president and secretary and such that no person belongs to both committees? How would we proceed?

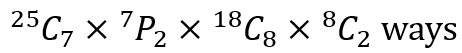

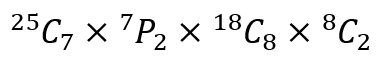

We could first select the 7 member committee, which can be done in 25C7 ways. Now among these 7 members, we have to choose 1 to be president and 1 to be secretary, which can be done in 7P2 ways. We use a permutation because it matters whether a person is president or if she is secretary. Now we have 18 people remaining. We can choose the second committee of 8 members in 18C8 ways and the president and secretary in 8P2 ways. So in all we have

Most textbooks will state that the answer is 49473074851200 or 4.947×1013 ways or something of the sort, where each individual term has been calculated and then the product evaluated. But this is an onerous task to do by hand. Hence, expecting the student to get either answer is expecting them to use a calculator. But perhaps the above number is too large for most of us to even process. Let’s deal with some smaller numbers.

Suppose I have 5 students. On one day, I wish to send a team of 3 of them for a debate. Quite naturally, this can be done in 5C3 = 20 ways. On another day, I need to send one student to the staff room to collect my books and another to the library to collect a journal. This can be done in 5C1 × 4C1 = 5 × 4 = 20 ways. Both tasks can be done in 20 ways. However, the number 20 obscures how it was obtained. If the textbook gives the answer as 20 for the first situation, but a student used the second method and obtained 20, she would think she has understood the concepts since she obtained the ‘correct’ numerical answer. However, her thinking is obviously flawed. However, if the textbook gave the answers as 5C3 and 5C1 × 4C1 respectively, any diligent student would be able to see where she had gone wrong.

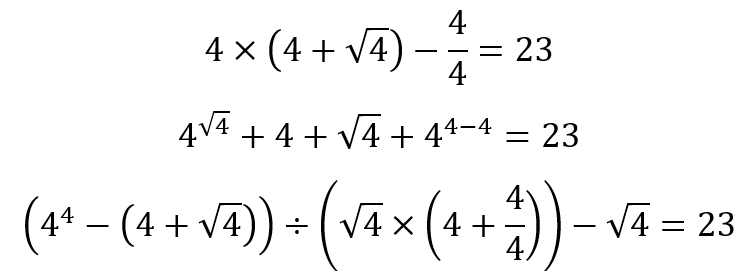

When I have taught large classes of students, I have often given them a random number and asked them to give me a series of operations with only a particular single digit number that would yield the random number. For example, suppose the random number is 23 and the chosen single digit number is 4. Then I could have

There are infinitely many ways in which I can use just the number 4 and obtain 23. The challenge would be for each student to give a unique set of operations. And when I have done this exercise, never once have we needed to repeat a set of operations.

What I am trying to say is that expressions such as 5C1 × 4C1 or 5C3 or, as in the original problem,

may be numerically equal to 20, 20, and 49473074851200 but contain far more information and give far more insight than the explicit numbers. However, if you are a calculator manufacturer, none of these insightful forms will help you sell your products!

Escaping the Trap

So you, that is, the calculator manufacturer, and the examination boards and the textbook publishers form a nexus in which these explicit but uninsightful forms are given preference over the forms that can be used to yield mathematical insight and promote mathematical understanding.

Unfortunately, most teachers go ‘by the book’. And so over time they forget that 3/4 and 6/8 may be numerically equivalent, but have quite different meanings. They forget that 20 is not just a number but could have been obtained in many ways, most of which are incorrect. They tow the line and look at the bottom line, that is, the final answer, concluding, if the answers match, that the student must have correctly executed the right sequence of operations. But as we have seen, this need not be the case.

It is time that the examination boards took a firm stance and actually favored the development of mathematical understanding of students rather than their ability to use a tool that is obsolete. I mean, where in the world does anyone use a calculator these days? Some old style retail outlets may use four function calculators to add the prices of items on a list and maybe also to calculate any sales tax or GST. However, where does anyone use a calculator for trigonometric or logarithmic or exponential functions except in school where it is forced onto the students? If we want students to be able to use some kind of technology to evaluate complicated functions, then we should teach them a programming language rather than make them use calculators. At least the former has real world relevance for many jobs while the latter has absolutely none!

Leave a comment