Looking Back, Looking Ahead

The response to last week’s post on geometry was heartening. So I thought I would give the readers another small dose of geometry. Some of the ideas that arise from geometry are simple, yet so profound that it is hardly surprising that geometry was considered the pinnacle of human wisdom by many early mathematicians and philosophers. In the previous post I had expressed by consternation at the fact that, in some countries, mathematics is split into independent siloes, thereby rendering it difficult, if not impossible, for students to fully appreciate the subject. Here I wish to consider two geometry problems that demonstrate how connected the different branches of mathematics actually are, focusing today only geometry and algebra.

Areas in a Quadrilateral

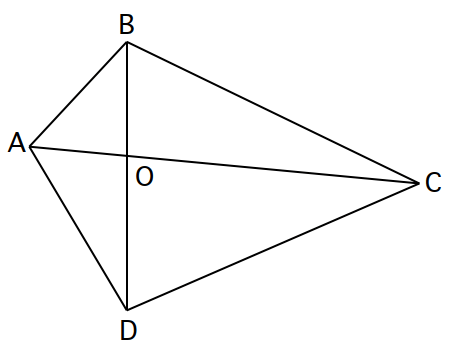

Let ABCD be the convex quadrilateral, as shown, and let O be the point of intersection of its two diagonals. Suppose the area of △ABD is 1, the area of △BCA is 2 and the area of △DAC is 3. Find the areas of △CDB and △ABO.

As usual, I suggest the reader pause here and try to solve this question before proceeding.

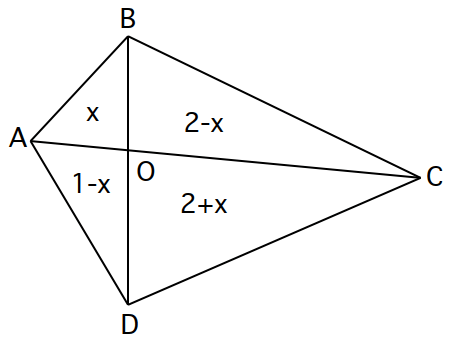

We can start by assuming the area of △AOB is x. This would mean that the area of △AOD is 1 – x and that of △BOC is 2 – x. This would mean that the area of △COD is 2 + x. This is shown below.

We can quite easily see that the area of △CDB is the sum of the areas of △BOC and △COD. Hence, the area of △CDB is 2 – x + 2 + x = 4.

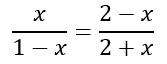

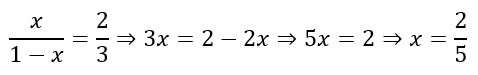

Now △AOB and △AOD have the same height. Their bases are OB and OD respectively. Similarly, △BOC and △COD have the same height and their bases are OB and OD respectively. Hence, the ratio of the areas of △AOB to △AOD is equal to the ratio of the areas of △BOC and △COD. This gives

Cross multiplying, expanding, and rearranging we get

Hence, the area of △AOB is 2/5.

Another way of solving the problem is to recognize that △ABC and △ADC have the same base AC. Hence, their areas (2 and 3 respectively) will be in the ratio of the lengths of BO and DO. Hence,

We can see that both solutions are relatively straightforward. However, it is clear that we have used algebra to solve the geometry question. Hence, if the mathematics curriculum is divided into separate study of algebra and geometry it will adversely affect the student’s ability to make both branches ‘speak’ to one another.

Stacked Trapeziums

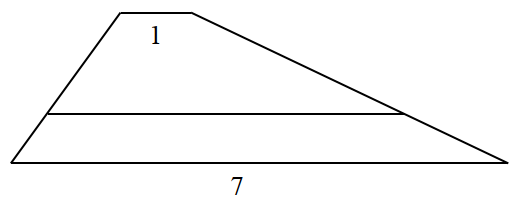

The parallel sides of a trapezium have lengths 1 and 7, and the area of the trapezium is divided into two equal parts by a line segment parallel to those two sides. Find the length of that line segment.

I urge the reader to pause here and attempt the question before proceeding.

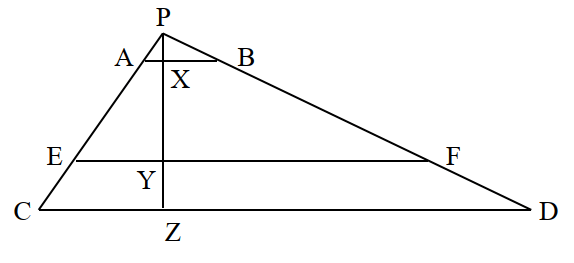

We proceed by extending the oblique sides until they meet at P. In this way they form triangles as shown below. We have also dropped a perpendicular from P intersecting AB, EF, and CD at points X, Y, and Z respectively.

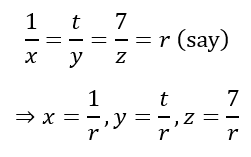

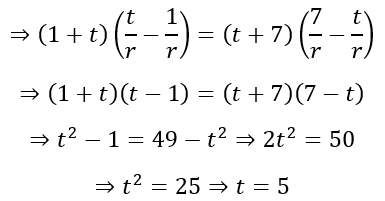

Now it is clear that △PAB, △PEF and △PCD are similar. If we set EF = t, PX = x, PY = y, and PZ = z, we can obtain

Now the heights of the trapeziums ABFE and EFDC are XY = y – x and YZ = z – y respectively. We are given that the areas of the two trapeziums are equal. Hence, we can conclude

Using the earlier expressions for x, y, and z we get

Hidden Gems

In both problems we see that a little algebra gets us a long way. While it is certainly possible to solve both questions without algebra, given the ‘nice’ numbers involved, the use of algebra simplifies things quite a bit. More to the point, though I did not mention it, the two solutions to the first problem actually rely on the commutative property of multiplication. That is, when we say that the area of a triangle is half the product of the base and the height, it does not matter which side we take as the base and which measure as the height (as long as it is truly a height corresponding to the chosen base). Specifically, whether AC is the base and BO and DO proportional to the height or BD the base and AO and CO proportional to the height makes no difference.

In the case of the second problem, the completion of the triangle allowed the comparison of similar triangles. While this is a stock move in geometry, the result that involves the difference of squares is something that might not have been easy to predict. Despite this, the significance of the difference of squares, where the sums represent the lengths of the parallel sides and the differences represent the heights of the corresponding trapeziums is something that only the interplay between the geometry and the algebra could have revealed. If, however, the student is allowed to play with ideas from both branches, it is highly likely that she will make the links herself and understand the meaning of what she is doing.

These insights are examples of hidden gems of mathematical knowledge that will remain hidden if we do not allow the different branches to ‘speak’ to each other. If we treat the different branches as independent fields of inquiry, however, we will give students the impression that it is possible – or, God forbid, preferable! – to study the branches in isolation from each other and still be able to obtain deep insights about the subject and the ideas it contains.

Leave a comment