The Presenting Problem

In this post, I wish to continue with some geometry along with some insights from sequences and series. Consider the figure below

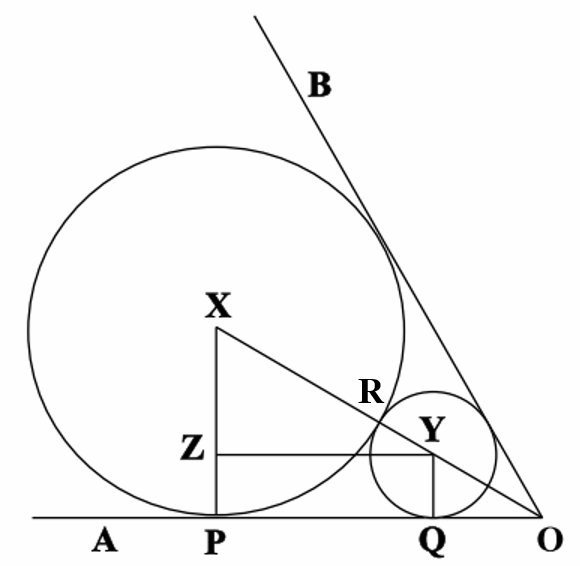

It is given that ∠AOB = 60°. Also, the radius of the largest circle is 1 unit. The successive smaller circles are tangential to the circles on either side. This continues indefinitely. In other words, there are infinitely many circles. We are asked to find the total area of all the infinite circles.

If you are inclined to solve this, please pause here before proceeding.

Introducing Infinite Geometric Series

Ok. I hope those who attempted the solution have obtained a satisfactory answer. Now, some of you may be wondering how the sum of the area of infinite circles could be determined. Should the finite area of infinite circles also be infinite?

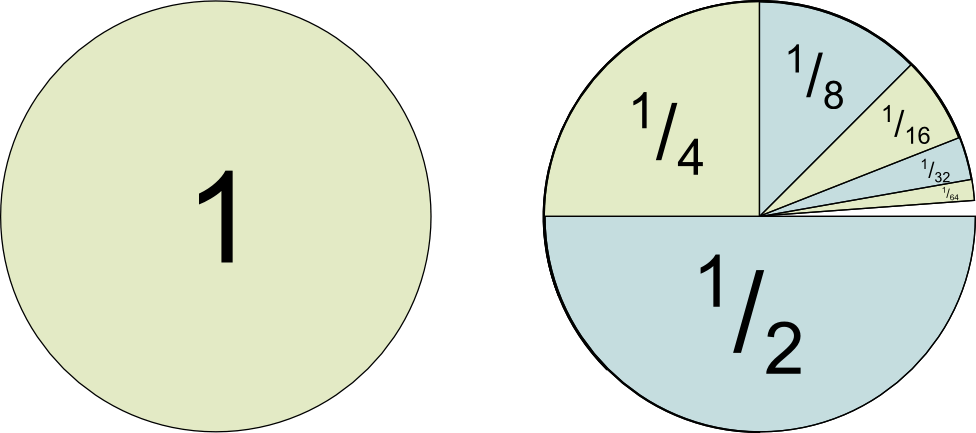

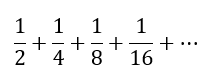

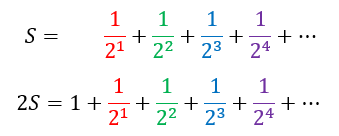

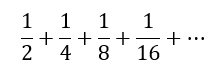

Let us take a brief detour into the marvelous world of infinite series. Consider the series

The ellipses (i.e. ‘…’) at the end indicate that the pattern continues. We encountered an expanded version of this series in the post Naturally Bounded. There we considered the infinite series

After some nifty algebraic manipulation we showed that S = 2. Since the sum we are considering in this post only lacks the starting 1, we can conclude that the sum of the infinite series for this post is 1.

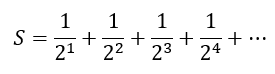

However, let us spend some time understanding why this is the case. What in the world is the pattern in our series? We can recognize that all the values in the denominator are powers of 2. Let us designate the sum with S. Then we can write

Now let us try to see why the sum turns out to be 1. As in the earlier post, we can multiply both sides by 2 to get

Let us make this colorful. We can write the above two equations one below the other as follows

We can see that, if we subtract the first equation from the second, the LHS will yield Sn, while the RHS will reduce to 1 since all the terms in red, green, blue, and purple will cancel out. This gives us S = 1.

But why does this work. We can see that, in the series we are considering, every term is obtained by multiplying the preceding term by 1/2. Such a series is known as a geometric series.

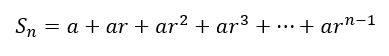

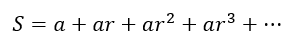

In order to understand geometric series, let us start with a general case. Let’s say that we have a starting term, a, and that each subsequent term is obtained by multiplying by r. The multiplier, r, is called the common ratio because it is the ratio of any term to the term before it. Anyway, we can see that our geometric series up to n terms will be

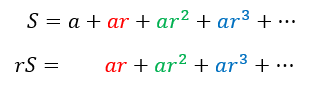

Note that the nth term is arn-1 because the first term, a, is actually ar0 and as the power of a starts from 0, the count after n terms will be n – 1. We can multiply the above equation by r and arrange a similarly color coordinated set of two equations one below the other as follows

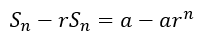

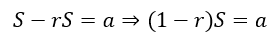

Now, when we subtract the second equation from the first, the red, green, blue, and purple terms will vanish, leaving us with

Both sides can be factorized to give

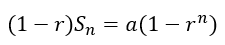

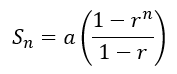

Now, if we divide the entire equation by 1 – r we will obtain

The first thing we can observe is the denominator 1 – r. Since the denominator cannot be zero, we can conclude that this formula will not work for r = 1. Further, we can take a look at the rn term. When the value of r is either greater than 1 or less than -1, multiplying by r results in a number that has a greater magnitude. In this case, it is obvious that we cannot find a sum of infinite terms of the series since subsequent terms have larger and larger magnitudes.

But what happens when the value of r is between -1 and 1? In this case, multiplying by r results in a number that has a smaller magnitude. Hence, the more times we multiply by r, the closer the result gets to zero. We can see this in the original series

We can see that each term is closer to zero than the one before it. So we can potentially consider an infinite series for these values of r and write

Once again we can multiply this equation by r and stack the two equations as follows

Now, when we subtract the second equation from the first, the red, green, and blue terms will vanish giving us

Dividing the equation by 1 – r we get

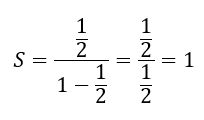

Now, we can return to our original series. For this series, we observe that a = 1/2 and r = 1/2. Plugging these values into the above formula gives us

Return to the Problem

This matches with our earlier result and puts us in a position where we can actually attempt the problem with which I started the post. Let me reproduce the figure so we can recall what the problem was.

Starting with the largest and second largest circles, we can obtain the following figure.

Here, X and Y are the centers of the larger and smaller circles respectively. XP and YQ are perpendiculars drawn from X and Y respectively to AO. YZ is a perpendicular drawn from Y to XP. Since we were given that the largest circle has a radius of 1, this means that XP = 1. Also, R is the point of tangency of the two circles, which is also the point where the line OX intersects both circles.

Now, we are given that ∠AOB = 60°. From symmetry, it follows that ∠AOX = 30°. Using some basic geometry, we can see that OX = 2 XP. Similarly, since the triangles OXP, PYQ, and YXZ are similar, we can obtain OY = 2YQ and XY = 2XZ.

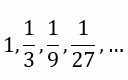

Suppose we say that YQ = r. This gives us OY = 2r. Also, since XP = 1, we can conclude that OX = 2. But OX = OY + YR + RX. This gives us 2 = r + 2r + 1, yielding r = 1/3. However, r is the radius of the smaller circle. Since, with the use of geometry, it turns out to be a constant (i.e. 1/3), this means that the radius of each successive circle in the series will be 1/3 times the radius of the previous circle. In other words, the radii of the circles form the following sequence

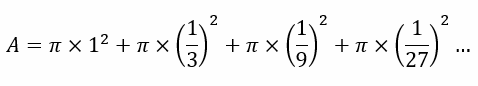

Now, the area of a circle is πr2. This gives us the infinite series for the area is

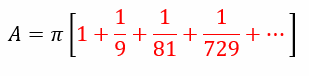

Taking π common we can express this as

Here, the terms in red form an infinite geometric series with a = 1 and r = 1/9. Using the formula we earlier derived for the sum of an infinite geometric series we can obtain

Reflection

While solving the problem we have used both algebra and geometry. In an earlier post I have bewailed the unfortunate trend in some countries of offering distinct mathematics subjects like Algebra 1, Geometry, and Pre-Calculus. In another post I demonstrated that one’s understanding of mathematics is furthered when we consider algebra and geometry together. I have done this in this post too. Mathematics is a coherent body of knowledge. By introducing artificially defined segments of mathematics as stand-alone bodies of knowledge, we convey the idea that the whole is the sum of its parts. However, mathematics is much greater than the sum of its branches. And I will continue to harp on this till my dying breath!

Leave a comment