Down Memory Lane

Just recently, while introducing me for a talk, someone stated that I have two loves – theology and mathematics. This is a reasonably accurate statement and I blog about these two areas regularly. I have been quite open about both of these with my students too. Hence, even though I am their mathematics teacher, they all know that I am also a pastor and that I think about theological issues. As a result many students often ask me questions related to issues outside the immediate sphere of mathematics.

Hence, way back in 2006, shortly after the movie was released, some students asked me about my take on The Da Vinci Code. Some of them, inspired by the movie, had started reading the novel by Dan Brown and had observed some differences between the book and the movie. They wanted to know which version was correct.

I had to disabuse – or at least attempt to disabuse – them of the notion that either the book or the movie had anything that could be considered historically reliable. Secret societies and hidden genealogies are all well and good for a novel, but they hardly hold up to rigorous scrutiny.

In 2006 I had neither seen the movie nor read the book. My work schedule only permitted time for one ‘distraction’ and, at that time, J. K. Rowling was regaling me with the adventures at Hogwarts, both on the page and on the screen. Having had a late start with the adventures of Harry, I was attempting to catch up and finish reading till the Half Blood Prince before the Deathly Hallows was scheduled to be published the next year.

One of my student expressed disbelief that I had not read the novel by Brown. She showed me the illustration of The Vitruvian Man in the novel and asked me how I, as a mathematics teacher, was not intrigued by the proportions of the human body that the drawing indicated. I had to tell her that, since humans come in all shapes and sizes, there is no ideal proportions for the body. After reading a bit about the Vitruvian man, I had to tell her that this was some idealized set of proportions that might have held some appeal for da Vinci, but that this does not mean it was some universal principle.

The Golden Ratio

She also expressed some interest in learning about the Golden Ratio, which she believed to reside in the drawing. But I had to tell her that this was impossible since da Vinci was working with ratios of whole numbers, which meant that he was not working with the Golden Ratio since the ratio is an irrational number. In this blog, I have dealt with two other irrational numbers at length – e and π. The Golden Ratio is a different sort of irrational number. Unlike e and π, which are both transcendental irrational numbers, the Golden Ratio is an algebraic irrational number.

Of course, here we come across something very strange. There are people who claim that the Golden Ratio has some inherent aspect of beauty to it and that, therefore, many artists use it in their art. Let me be very blunt. Even if it is the case that the work of some artists might seem to indicate that there are some ratio similar to the Golden Ratio, and even if some artists today might be intentionally trying to include the Golden Ratio in their work, there is absolutely no justification, from a mathematical perspective, to think that there is any truth to such claims. In order to justify my assertion, let us consider what the Golden Ratio is.

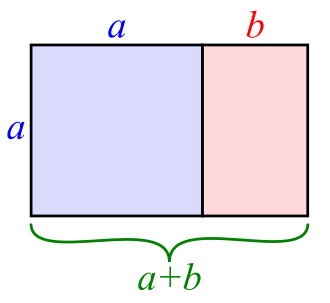

Suppose we have a rectangle with smaller side of length a and larger side having a length a + b. Now suppose we cut off a square of side length a from the rectangle. This would leave a rectangle with sides of length a and b. This is shown in the diagrams below

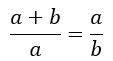

Now if the ratio of the lengths of the sides of the original rectangle is the same as the ratio of the lengths of the sides of the smaller rectangle, then we say that the ratio of the lengths of the sides is the Golden Ratio. This gives us the equation

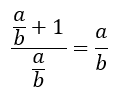

Dividing the numerator and denominator of the left fraction by b we get

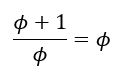

Denoting a/b as ɸ we get

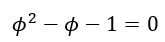

This can be rearranged to give the quadratic equation

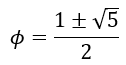

Using the quadratic formula, we can obtain

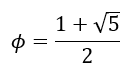

Since ɸ is a ratio of lengths, it cannot be negative. Hence, ignoring the negative root above we get

Using a calculator, we can obtain ɸ = 1.618033989…. The presence of the square root of 5 in the expression for ɸ indicates that it is an irrational number, as I claimed earlier.

An Oft-Repeated Claim

However, the irrationality of the ratio cannot be the only reason for which I reject the claims about its prevalence in art. After all, the diagonal of a unit square is √2, which is also irrational. Similarly, the ratio of the distance between parallel sides of a regular hexagon to the length of the sides is √3. While artists, in general, may not use geometric figures in their art, it would be fallacious for me to discount the presence of some ratio simply on the grounds that it is irrational.

The claims about art do not come on their own. Rather, there is the prior claim that the Golden Ratio occurs often in nature. This is a bald-faced lie. After all, what can we observe in nature but discrete occurrences of phenomena? That is, we can count certain things. For example, it is claimed that, if we count bands of fruitlets on pineapples, we will count 5, 8, or 13 bands for small pineapples or 8, 13, and 21 bands for larger ones. So what?

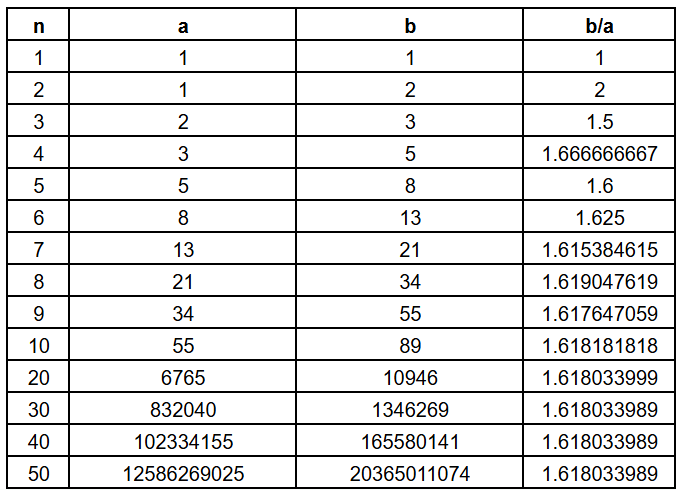

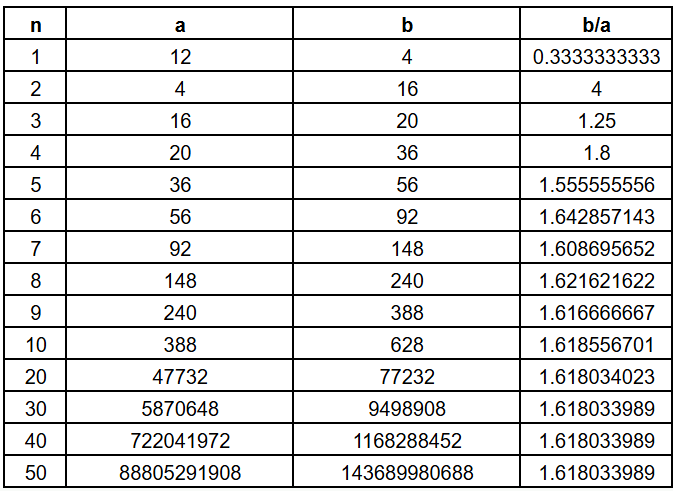

Well, these numbers are consecutive numbers in the Fibonacci sequence. And if we take the ratio of consecutive terms in the sequence, the ratio will turn out to more closely approximate ɸ. For example, see the table below

I have collapsed many of the rows so that the table could fit and be readable in a single screen. However, the table shows that the terms in the fourth column converge to the value of ɸ indicated earlier. It is crucial, however, to note that, while the ratio in the fourth column do converge to the value of ɸ, they will never be equal to ɸ because the ratios are rational numbers while ɸ is irrational.

Debunking the Claim

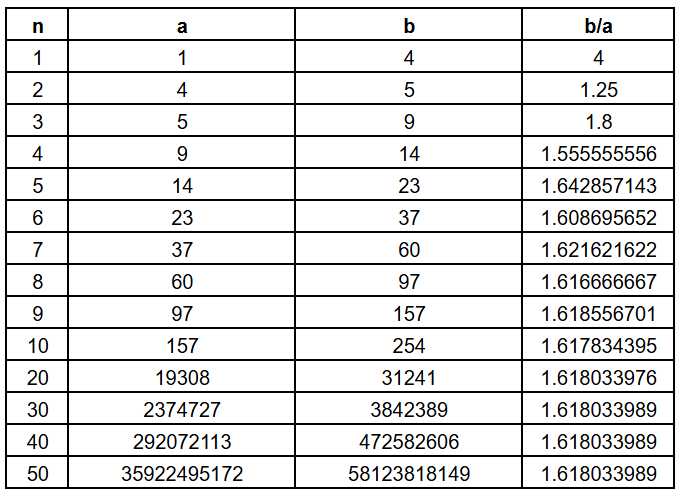

But that’s not my beef with the earlier claims. Let us start the sequence with different numbers. Instead of the first two terms being 1 and 1, let us start with 1 and 4. Note that 4 does not appear in the original sequence. With these two as the starting point, we will get the following table

Since the starting terms are different, all the terms in the new sequence differ from the original one. However, the ratios quickly converge to the same value!

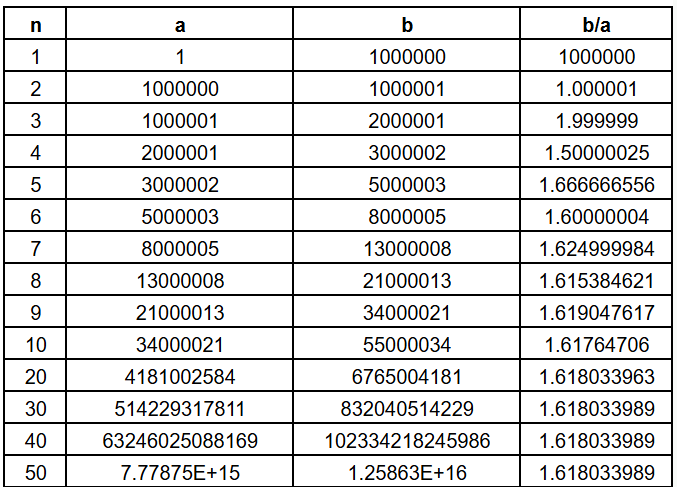

Now let us change the second term quite drastically. Let’s make it 1,000,000! Now we get the following table

We observe the same thing, namely that, while the individual terms are the ratios converge to the same value.

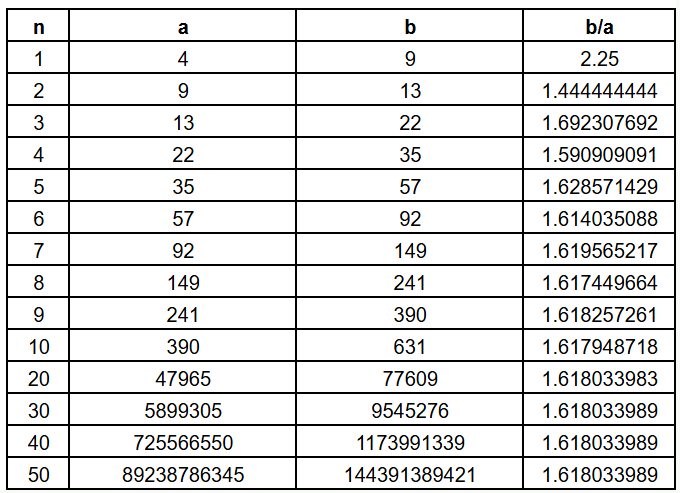

We could take a different first term also and see what we get. Choosing a = 4 and b = 9 we get the following

There is no change to the ratio to which the terms of this sequence converge. Indeed, we can start with a value of a that is greater than b and get something like

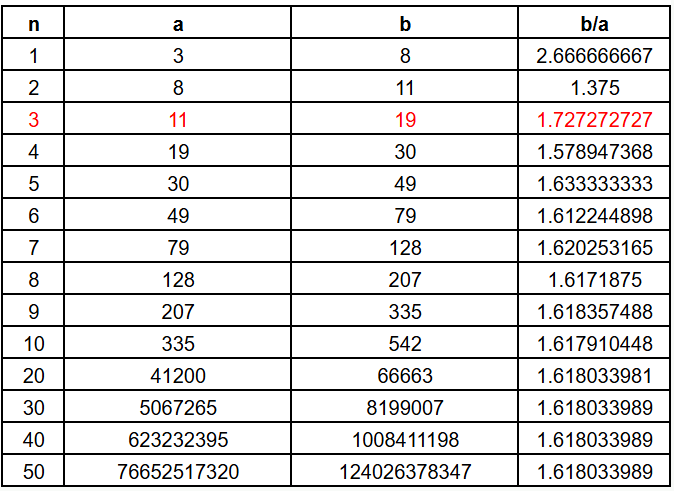

In other words, no matter what numbers we choose to start with, the resulting ratio of consecutive terms converses to the value of ɸ. Hence, if you give me any two starting numbers, I can confidently assert that they are part of a sequence where the ratios of consecutive terms converges to ɸ. For example, if you gave me 11 and 19, I could form the sequence as below

Here, I have shown the third row in red so you can see where in the sequence the given numbers lie. And since the sequence of ratios converges to ɸ, I can confidently state that, if we find the numbers 11 and 19 in nature, then this must be an approximation to ɸ. But the careful reader will recognize this as quite spurious reasoning. After all, every pair of starting numbers will yield a sequence of ratios that converges to ɸ. Hence, there is nothing extraordinary in finding any such pairs of numbers anywhere.

Freedom to Explore

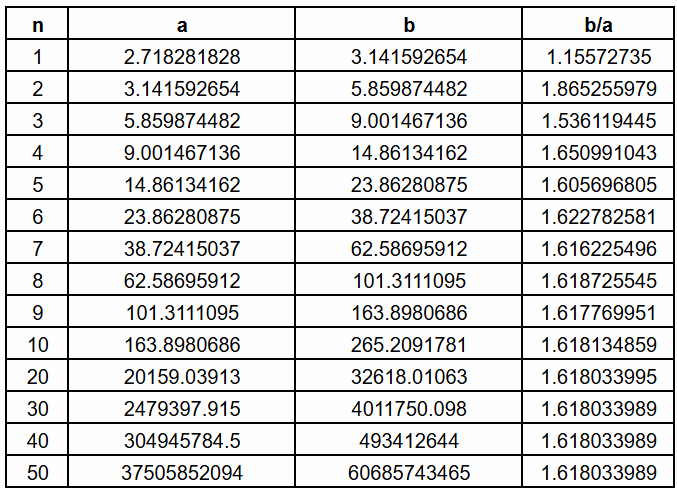

Over my career as a teacher, which spans more years than I would care to admit, I have come across the claim that the Golden Ratio appears in nature many more times than I would consider acceptable. Most of these are from excited young students, who have just been introduced to the Golden Ratio or the Fibonacci sequence. However, a fair number are from teachers, some very experienced in terms of years. They point to the fruitlets of the pineapple and to the petals of various flowers to give their students examples of these presumed occurrences. However, as I have shown in this post, any starting point, as long as both numbers are positive, will result in a sequence of ratios that converges to ɸ. Here is one that starts with the transcendental number e and π.

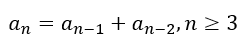

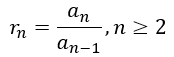

By pointing to numbers in nature and asking their students to draw conclusions that nature has examples of the Golden Ratio, such teachers are stunting the mathematical acumen of their students because they make the students think that something is special when in case it is nothing more than run of the mill. Instead of asking their students to wonder why every sequence of numbers defined as

has a corresponding sequence of ratios defined as

that converges to ɸ, the teachers make students think that the example of the Fibonacci sequence is unique in that regard.

Don’t get me wrong. I am not saying that the Fibonacci sequence does not represent something insightful about mathematics. What I am saying is that we should not claim any distinction for it that it actually does not have. But for this to happen the teachers should have the time to explore various ideas both individually and in groups. However, given how content heavy the high school mathematics curriculum is, teachers in the lower grades also have a lot to cover.

As a result, most mathematics teachers are perpetually scrambling to complete the syllabus for the year, with hardly any time for the kind of exploration that would result in robust learning for the students. Because of this, most teachers are forced to use prepackaged material, such as from a textbook or online platforms. But prepackaged materials can never cater to the unique requirements of a class of students, each of whom has a uniquely expressed curiosity, unless, of course, we wish to quench that curiosity!

If we are serious about teaching students to be adept at mathematics, we must reduce the content of our curriculums and syllabuses and focus instead on the development of a small set of skills that can be transferred not just to different areas within mathematics but also to other disciplines. And we must allow our students – and teachers – the freedom to explore the subtleties of mathematics without which their understanding of mathematics would be superficial at best.

Note: I will be taking a break next week and will return with new posts in January 2025. Have a happy holiday season.

Leave a comment