‘Sining’ In

We are in the middle of a pit stop in the middle of our series on complex numbers. The pit stop is intended to introduce the reader to the basics of trigonometry. In the previous post, we saw why we have 360° in a circle and 90° for a right angle. We also defined the radian, which I demonstrated was not an arbitrary unit, unlike the degree. In the post preceding that, we saw how partnership between mathematicians from India, Persia, Greece, and Rome gave us the names of the trigonometric ratios.

At the conclusion of this pit stop, when we return to complex numbers proper, we will see how integral the ideas we uncover in trigonometry are to the study of these numbers. For now, as we begin the next part of our pit stop, let us remind ourselves about the definitions of the trigonometric ratios.

Nomenclature

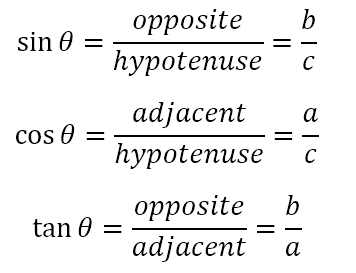

With respect to the figure above, the angle we are focusing on is ∠ABC, which we are calling θ. The side opposite θ is AC, which has a length equal to b. The side adjacent to θ is BC, which has a length equal to a. Finally, the hypotenuse of the triangle is AB, which has a length equal to c.

Per our definitions of the trigonometric ratios

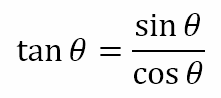

The three ratios relate as follows

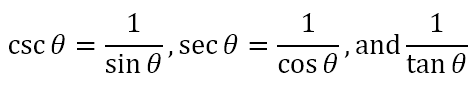

We also define three other ratios as follows

Here, csc stands for cosecant, which is often shortened to cosec. Similarly, sec is short for secant and cot is short for cotangent. With reference to the post made two week back, I leave it to the reader to discover why the secant has its name.

Pythagoras Again

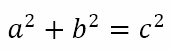

Now, from Pythagoras’ theorem applied to the triangle ABC, we know that

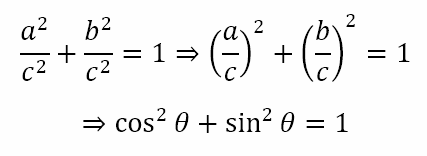

If we divide the entire equation by c2, we will get

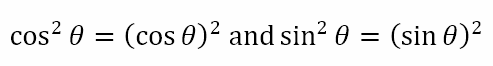

Pay close attention to the notation above. What the last equal says is that

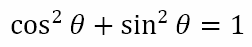

Consider the equation

This is the first identity students learn in trigonometry. It is called a Pythagorean identity because it is derived from the Pythagorean theorem. But what do we mean by an identity?

An identity is a mathematical statement that is true for all values of the variables. In the above equation, the angle θ is the variable since we did not decide on its value. The equation

is true for all values of θ and is, therefore, called an identity. An identity, while in this case written in the form of an equation, differs from common equations in that one cannot ‘solve’ an identity to obtain a value of the unknown since it is true for all values.

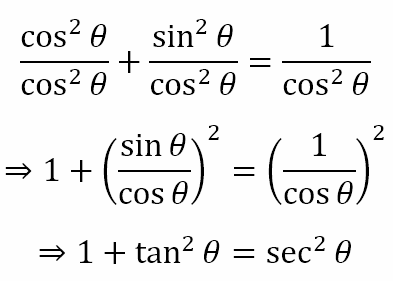

Now, starting with this identity, let us divide it by cos2θ. We would then get

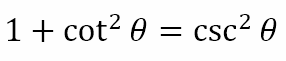

This last equation is also a Pythagorean identity since it too is derived from the Pythagorean theorem. The reader can begin with the first identity and divide it by sin2θ to obtain the third Pythagorean identity

Proving Identities

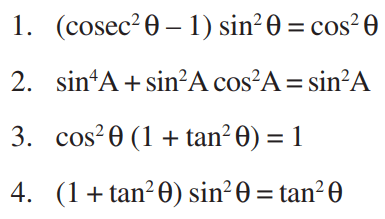

Note that the two additional Pythagorean identities did not require any additional trigonometry apart from the definition of the secant, cosecant, and cotangent. This is a big feature in trigonometry, where new identities can be proved based on existing ones. Let us consider some examples.

Example 1

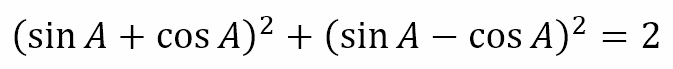

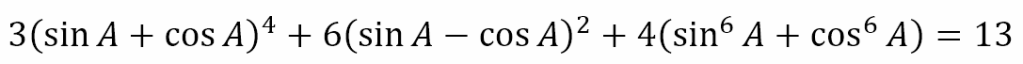

Suppose we were asked to prove that

We could proceed as follows

Here LHS and RHS denote ‘left hand side’ and ‘right hand side’ and indicate the direction in which we are moving to prove the identity.

Example 2

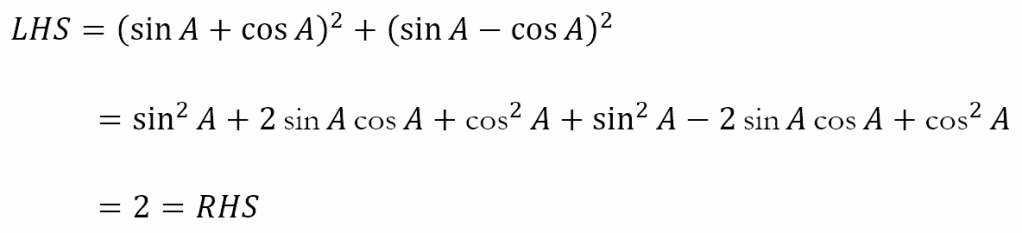

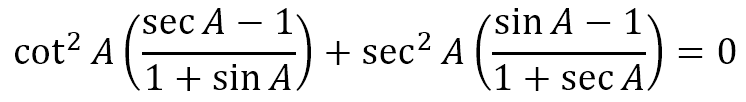

Let’s consider another example. Suppose we were trying to prove that

We could proceed as follows

While this proof is longer than the earlier one, note that in both we use simple algebra, such as was discussed earlier in Primer to Complex Numbers, the post with which I began the series on complex numbers.

Example 3

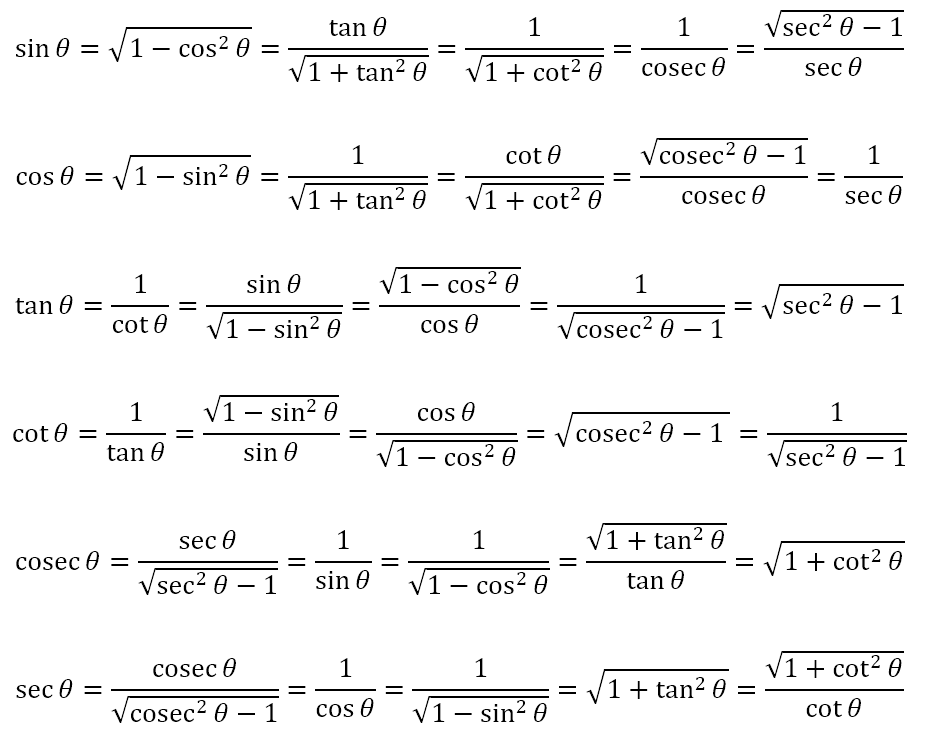

As a final example, suppose we were asked to prove

We could proceed as follows

Interrelatedness of the Trigonometric Ratios

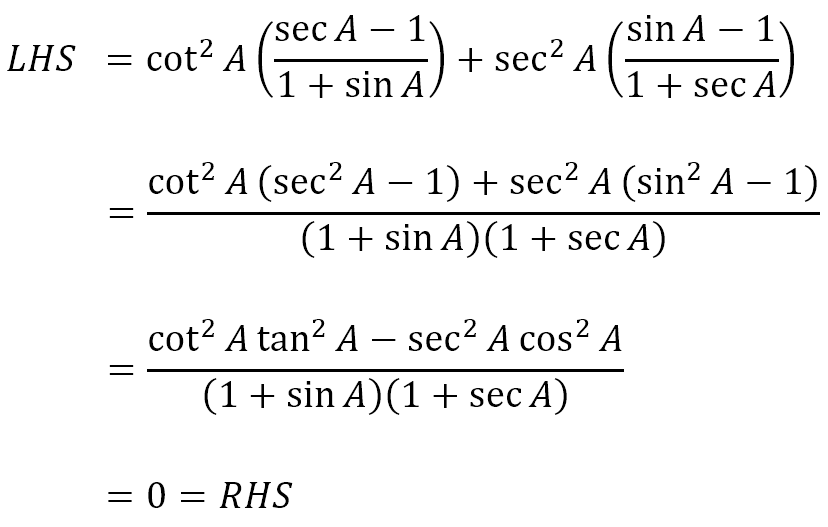

Note that, along the way, we made use of the Pythagorean identities quite often. This is because the trigonometric ratios simply conceal the Pythagorean theorem in their definitions. In fact, because of this feature, namely that all the ratios are related to each other through the Pythagorean theorem, we can actually show the following

That is, each of the ratios can be expressed completely in terms of any one of the other ratios.

‘Sining’ Off

However, if you have been paying attention, you will realize that we have a problem. We know that no triangle can have an angle equal to 0° or 180°. We also know that a right angled triangle cannot have another right angle. We also know that a right angled triangle cannot have an obtuse angle or a reflex angle. In other words, defining the trigonometric ratios in terms of lengths of sides of a right angled triangle means that most of the angles cannot have trigonometric ratios defined for them. This is a remarkable drawback. However, mathematicians have gotten around this restriction in quite an ingenious manner. We will turn to that in the next post. Till then here are a few identities you can try proving.

Leave a comment