Resumption

Last week I had taken a break for Good Friday. For those who are interested, I used a random event for my sermon. If you’re interested, you can find it here. Anyway, with the break behind us, we resume the series on complex numbers. In the previous post of the series, Pole Vaunting, we had introduced the idea of the argument of a complex number. Before that, we had a six part pit stop, in which we learned some trigonometry, especially as it relates to complex numbers. Before the start of the pit stop, in Modulating an Invariant Metric, we had introduced the idea of the modulus of a complex number.

Revisiting the Polar Form

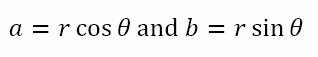

With the modulus and argument of a complex number, we specify the complex number in terms of its polar coordinates. With these polar coordinates, we are able to locate any complex number on the complex plane. The modulus tells us how far the point representing the complex number is from the origin and the argument tells us the angle made with the positive real axis by the line joining the origin to the point representing the complex number. In particular, we have seen that the complex number z = (r, θ) in polar coordinates is the same as the complex number z = (a, b) in Cartesian coordinates, where

That Old Friend Again

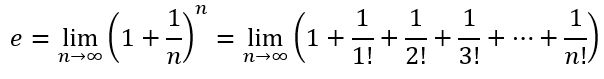

If you have been following the blog, you may vaguely recall that I had done a short series on the number e. In Naturally Bounded?, I had shown that

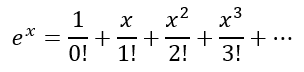

Then, in Return of an Old Friend, we saw that this could be extended to

However, we didn’t really prove the above result. And that is because we had not formally dealt with calculus. In fact, till today, we have not done that in the blog. However, I realize that, in order to do a sufficiently robust job in our journey ahead with complex numbers, I will need to at the very least dip my toes into the ocean of calculus. Hence, I will start another pit stop next week with a brief journey through calculus. But for now, I wish to explore some ideas we uncovered.

Rotational Rumination

In the previous post we saw that multiplying two complex numbers resulted in the multiplication of their moduli and the adding of their arguments. That is, if z1 = (r1, θ1) and z2 = (r2, θ2) then z1z2 = (r1r2, θ1+θ2). Now, let’s ask ourselves under what conditions does multiplication of a ‘two-part’ number result in the multiplication of one part and an addition of the second part?

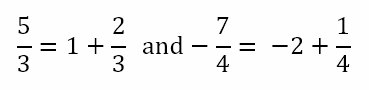

The term ‘two-part’ number, of course, is poorly defined. Someone could think of a rational number as having two parts – the integral part and the fractional part. For example,

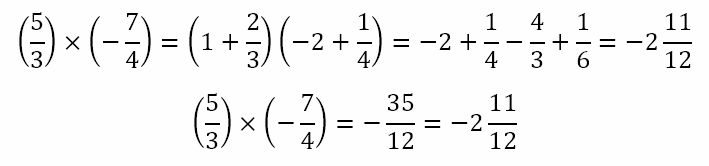

However, when we multiply two rational numbers, both parts get multiplied. This can be seen by both approaches shown below.

What this tells us is that the parts of complex numbers in polar form (i.e. the modulus and argument) do not function like the integral and fractional parts of rational numbers. What other ‘two-part’ numbers can we think of?

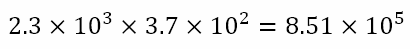

We can consider numbers written in scientific notation. For example, 2.3 × 103 has a mantissa or significand of 2.3 and an exponent or power of 3. Now, we can consider

What we can see is that the mantissas were multiplied while the exponents were added. This is similar to our saying that, when two complex numbers are multiplied, their moduli are multiplied while their arguments are added. Hence, it sees that there should be a way of expressing complex numbers in a ‘two part’ form where one part is a regular real number, similar to the mantissa, while the other part is written in exponential form, similar to the exponent.

However, we observe that, when we write z1z2 = (r1r2, θ1+θ2), the modulus of the product complex number z1z2 is given by the first part r1r2. However, we have seen that a complex number, represented in polar form, has a ‘size’ (i.e. its modulus) and an ‘orientation’ (i.e. its argument). Since in the product z1z2, r1r2 already expresses the modulus of the product in a manner similar to the mantissa, it must follow that θ1+θ2, which represents the argument of the product, corresponds to the exponent of the ‘two part’ number.

What this means is that there must be a way of representing complex numbers with two parts, similar to what we use in scientific notation, with the part corresponding to the mantissa representing the modulus and the part corresponding to the exponent representing the argument of the complex number. Since the modulus is a simple number, it must follow that it corresponds to the r of the polar form (r, θ). Hence, there must we a way of expressing the argument θ as the second, exponential part of the ‘two part’ number.

This is somewhat counterintuitive since, in conventional scientific notation, the exponential part conveys the ‘size’ of the number in terms of consecutive powers of 10 between which the number lies. That is, when we write 2.3 × 103, we know this number lies between103 and 104. However, 2.3 × 1032 is a number that lies between1032 and 1033. So, the exponential part gives the ‘size’ of the overall number, while the mantissa only locates the number between the two consecutive powers of 10.

However, now we are saying that there is an exponential form for complex numbers in which the modulus (i.e. size) is represented by the part similar to the mantissa while the argument (i.e. orientation) is represented by the part similar to the exponent. In other words, we are looking for some kind of exponential form involving θ that represents pure rotation.

Spiraling Away

Of course, since I went on a short detour earlier with e, you might be thinking that e has some role to play in this exponential form that represents pure rotation. You would be right! Of course, if you have studied complex numbers before, this will not be news to you. However, I’ll bet the reasoning toward this realization is somewhat novel. Anyway, the exponential form of complex numbers is an extremely powerful form. I could, of course, simply tell you what it is without any foundation for understanding how it is obtained. But that would be to short-change you – something I’d rather not do. Hence, as mentioned earlier, I will begin a second pit stop in the next post with some introductory explorations of calculus.

Leave a comment