Signing In

In the previous post, Deriving Derivatives – Part 1, which is part of the second pit stop in our exploration of complex numbers, we had derived the derivatives of xn and sin x. I had informed you that we will derive the derivatives of the exponential and logarithmic functions. In case some of you are unclear what these two words mean, let me begin with a brief introduction to exponents and logarithms.

Laws of Exponents

When we write 3x, what we mean is x is added to itself 3 times. Hence, 3x = x + x + x. Hence, we are taught that multiplication is repeated addition. Of course, we can conceive of repeating multiplication itself. For example, there is nothing to stop us from evaluating 4 × 4 × 4 = 64. Of course, if there are a small number of identical numbers being multiplied by each other, we may not feel the need for a more compact notation. However, if we had to multiply 42 identical numbers by each other, it would be quite a tedious business to write this down. Hence, we express 4 × 4 × 4 as 43, where the number in the superscript tells us how many of the numbers in the regular script are multiplied by each other. In this notation, the 4 is said to be the ‘base’ while the 3 is called the ‘exponent’.

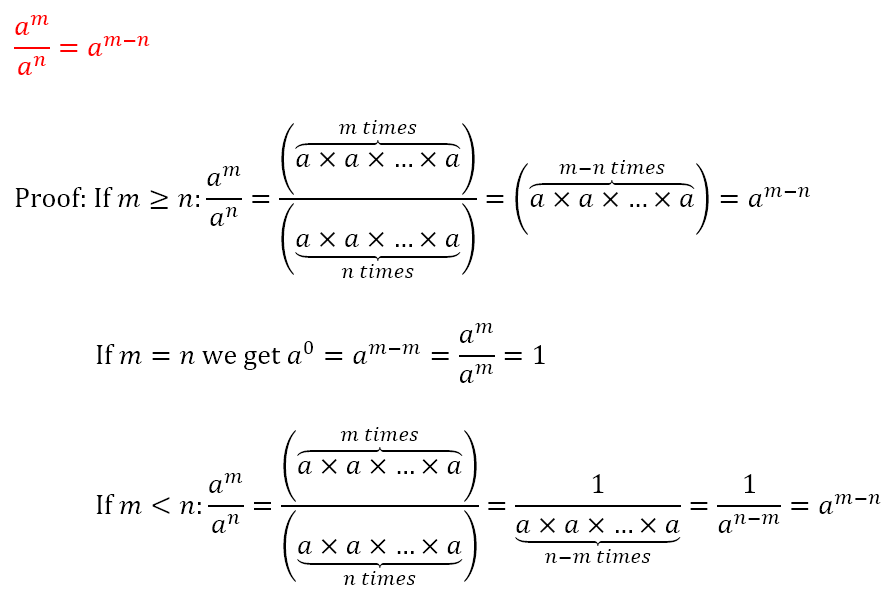

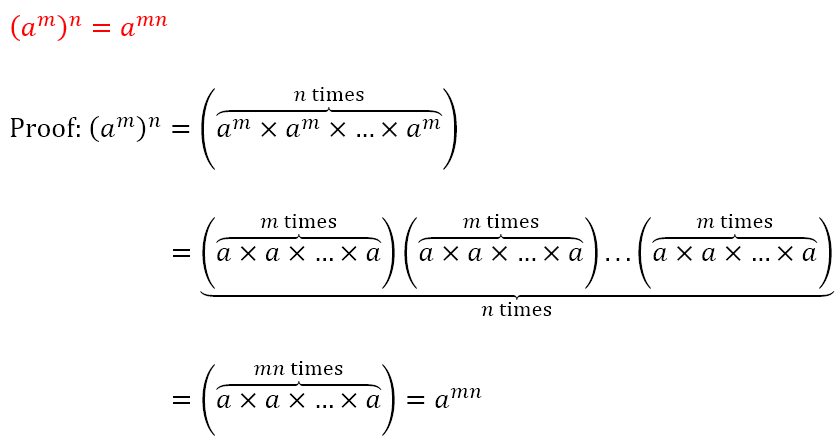

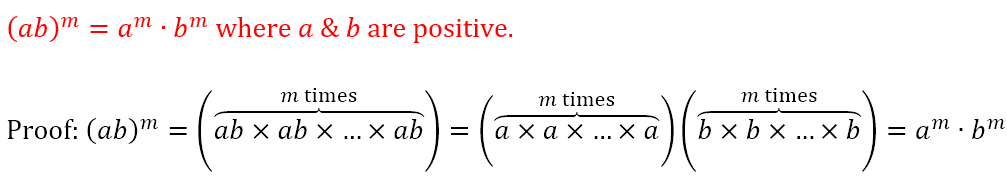

Using the definition of the exponent, we can obtain the following laws of exponents.

The Exponential Function

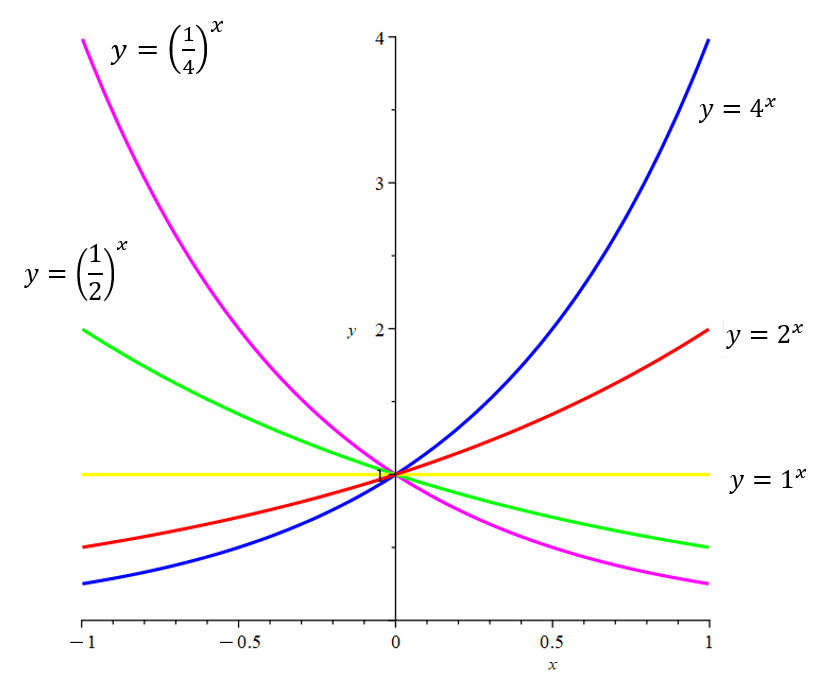

When we refer to an ‘exponential’ function, what we mean is a function in which the variable is in the exponent. Hence, if the variable under consideration is x, then 3x, 5x, πx, etc. are called exponential functions with bases being 3, 5, and π respectively. When dealing with real valued functions, that is functions that relate real numbers to other real numbers, we only allow the base to be positive. This is because the square root of a negative number is not a real number but an imaginary number.

Now, we had earlier gone through a series on e. The function ex is considered to be the natural exponential function because it represents a 100% growth rate compounded over infinitely many infinitesimally small compounding intervals. For an explanation of this, see What’s Natural About e?, the post that launched the series on e. We will shortly look at some properties of ex related to limits and differentiation.

Laws of Logarithms

However, if we can relate one real number to another through exponents, it should be possible to go the other way. This gets us to what is known as a logarithm. Logarithms are defined as follows: If an = x, then n = logax. We read the previous statement as follows: If a to the power of n is equal to x, then n is equal to the logarithm of x to the base a. In other words, what we have been calling the ‘exponent’ is, when we go the other way, called the ‘logarithm’.

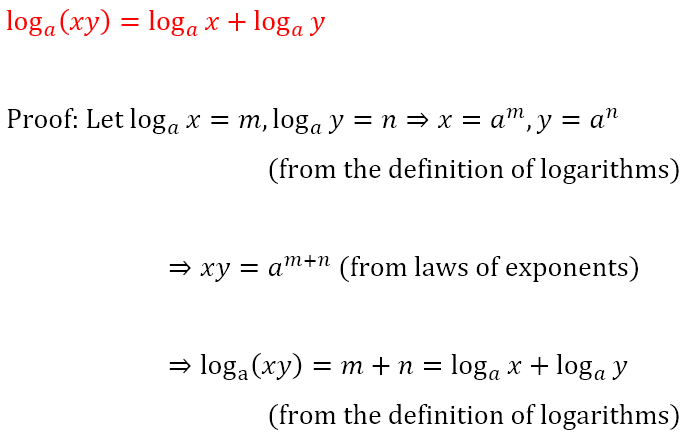

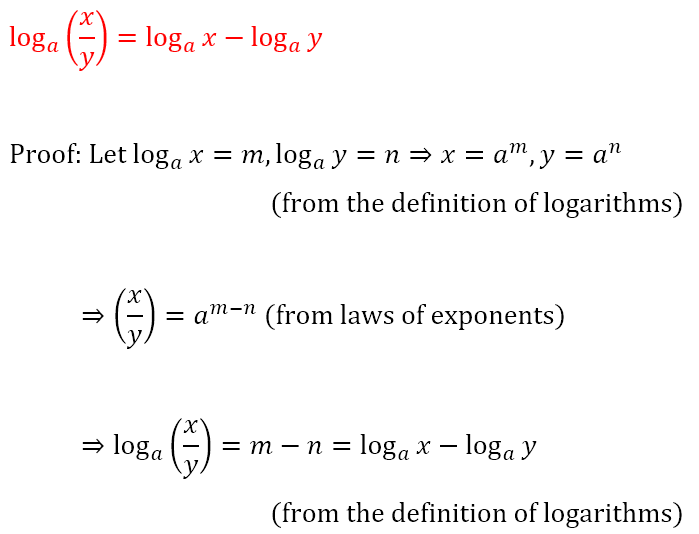

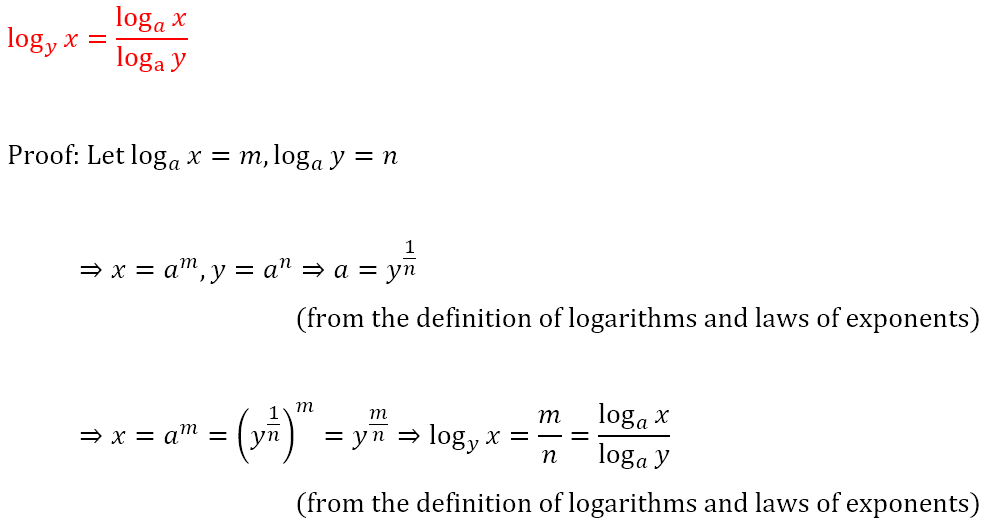

Once again, using the definition of the logarithm, we can obtain the laws of logarithms.

The Logarithmic Function

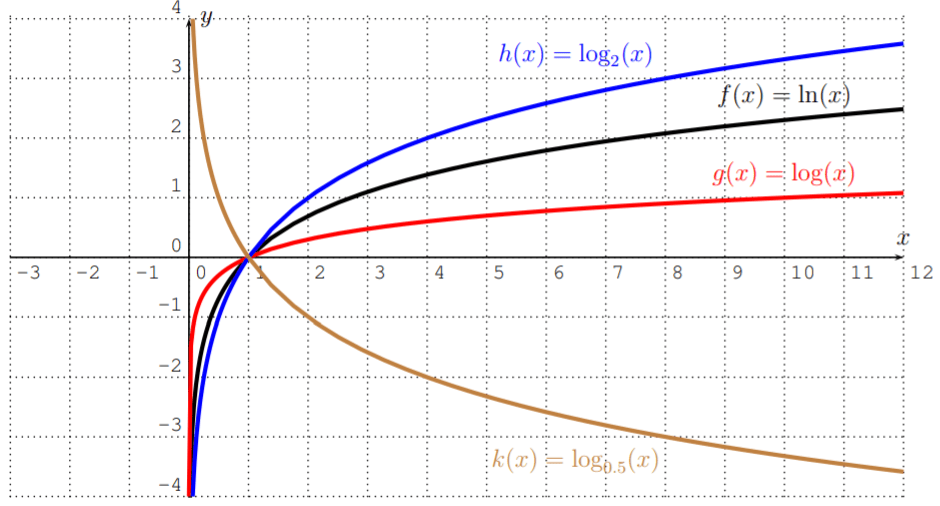

Similar to the exponential function, we can define a logarithm function logax, which is the power to which a must be raised to produce x. And similar to the natural exponential function, we have a natural logarithm function where the base is e. Since logarithms were first used in the decimal system, the notation logx is often taken to imply base 10, while the notation lnx is often used to denote the logarithm to base e. We will also take a look at some of the properties of lnx shortly.

The Derivative of ex

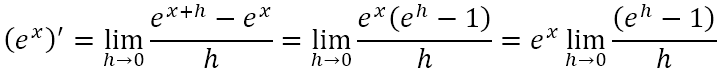

Since we are dealing with calculus in this pit stop, let us attempt to obtain the derivative of ex. By the definition of the derivative

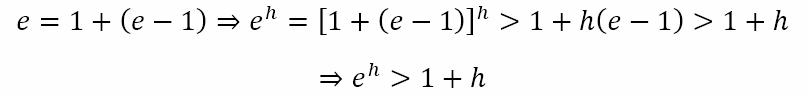

Now, that final limit is something we haven’t seen before. Let us obtain it in a rigorous way. From our study of e, we know that 2 < e < 3. This means that e – 1 > 1 > 0. That is e – 1 is a positive quantity.

Now, consider the expansion of (1 + p)2. Since (1 + p)2 = 1 + 2p + p2, it follows that, for positive values of p, (1 + p)2 > 1 + 2p. In a similar way we can show that (1 + p)3 > 1 + 3p. Continuing in this way, we can generalize that (1 + p)h > 1 + hp. Using this we can obtain

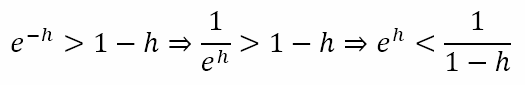

Replacing h with –h, we get

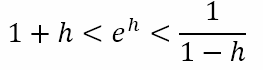

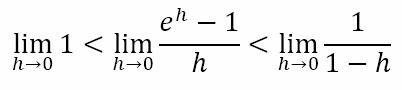

Note that, if h > 1, the final inequality would have to change sign. However, since h → 0, 1 – h will be positive and the above will be true. Combining the two inequalities we get

From this we can obtain the following

Now we can use the sandwich theorem as follows

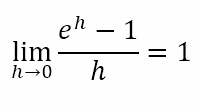

And since the left and right limits evaluate to 1, we obtain

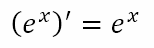

Hence, we can conclude that

The Derivative of lnx

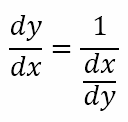

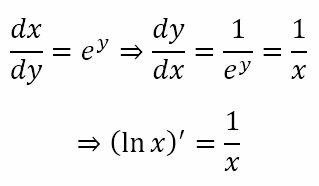

Having obtained the derivative of ex, let us turn our attention to lnx. Rather than use the definition of the derivative, which we can certainly do as we did above, I will use a little bit of intuition. Suppose a car is traveling at 10 meters per second. I can also write this as 0.1 seconds per meter. What this means is that the rate at which one variable (say y) changes with respect to another (say x) is the reciprocal of the rate at which the second (i.e. x) changes with respect to the first (i.e. y). We can write this as

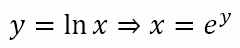

Now suppose y = lnx. From this we can get

Now, we have expressed x as a function of y. Differentiating this with respect to y we get

Signing Off

In this post, we derived the derivatives of ex and lnx. In the previous post we had obtained the derivatives of xn and sinx. In much the same way as we obtained the derivative of sinx, we can show that the derivative of cosx is -sinx. In the next post, we will look at infinite series and consider some conditions under which these series converge. That will place us in a position to use what we have uncovered so far in this pit stop to step back into the main series on complex numbers where we can return to the exponential form of complex numbers and some associated results.

Leave a comment