Abjuring Serialization

Last week we finished a series on complex numbers. During this series, we took two pit stops to learn about trigonometry and calculus. Quite obviously, I have not exhausted any of these three topics. However, planning these long series is exhausting! So, for a few posts, I will refrain from serialization. Instead, I will focus on some one-off posts. I will also tone down the level of the posts to make them a little more accessible since the series on complex numbers did prove to be quite heavy.

Now, in the minds of many, mathematics is taken to be the quintessentially objective field. After all, it is governed by logic and uses rigorous methods of proof. While this is true for the most part, there are times when some arbitrariness is permitted into the ‘rules’ of mathematics because the arbitrariness serves a greater goal. I’d like to call these instances of ‘cooking the books’ and here I’d like to discuss two such instances.

In Its Prime

I don’t know when I was introduced to the prime numbers. However, I do remember wondering why they were given this name. I mean, ‘prime’ sounds like these numbers are somewhat better or more important than numbers that are not ‘prime’. Despite this initial distraction, I found myself fascinated with these numbers. A prime number is defined as a natural number which is divisible only by 1 and itself. Hence, 2 is a prime number. So are 3, 5, 7, and so on. However, 4, 6, 8, and 9 are not because they have additional divisors other than 1 and themselves.

Most students learn this kind of definition early on. However, I have discovered of late an alarming trend. Many students reach high school not knowing whether 1 is a prime number or not nor any reason for their answer.

Now, if you scour the internet, you will find many sites that explicitly state that prime numbers have to be greater than 1. A few state that a prime number has to have two distinct divisors, thereby excluding 1 from the set of primes. In other words, the consensus is that 1 is not a prime.

But why not? What would be the disastrous consequences of allowing 1 to be a prime? One of the main theorems of arithmetic, betrayed by its name is the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic (FTA), which states that every natural number greater than 1 is either prime or can be expressed uniquely as the product of prime numbers, apart from the order of the primes. Note the critical word ‘uniquely’ and the phrase about the order. So, for example, 12 = 2 × 2 × 3 = 2 × 3 × 2 = 3 × 2 × 2. Note that, since multiplication is commutative, that is the order of the products does not affect the product, the three products represent the same set of two ‘2’s and one ‘3’.

However, note that the FTA itself excludes 1 by starting with natural numbers greater than 1. What gives? Actually, this exclusion gives us a hint of why 1 is excluded from the set of primes.

Suppose 1 is included in the set of primes. Now, 1 is the multiplicative identity element. (Math jargon alert!) What that means is that, when you multiply any number by 1, the product is the number you started with. So we have 3 × 1 = 3, 7 × 1 = 7, and so on. But what this obviously means is that 1 × 1 = 1. And here we see the beginnings of the problem.

If 1 = 1 × 1, then 1 = 1 × 1 × 1 and 1 = 1 × 1 × 1 × 1, and so on. Indeed, one of the few things most students remember is that 1n = 1 regardless of what n is. This obviously means that no number can be uniquely expressed as the product of primes. After all, we have 12 = 2 × 2 × 3 = 1 × 2 × 2 × 3 = 1 × 1 × 2 × 2 × 3 and so on. Indeed, there would not just be no uniqueness to the product, there would actually be an infinitely many products that could be written for any given number.

While having an infinitely many products for a given number might not seem too troubling, it’s the reverse process that raises problems. If any number can be written as the product of any number of numbers, then how do we determine the number of factors that a number has? For example, if 12 = 2 × 2 × 3, we can count and determine that there are 6 factors, inclusive of 1 and 12. However, if 12 = 1 × 2 × 2 × 3, the number of factors remains 6 but only an explicit enumeration of the factors can give us this result. What do I mean?

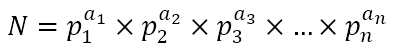

Consider 12 = 2 × 2 × 3. Any factor of 12 must necessarily be the product of powers of 2 from 20 to 22 and powers of 3 from 30 to 31. For example, 1=20 × 30, 2 = 21 × 30, 3 = 20 × 31, 4 = 22 × 30, 6 = 21 × 31, and 12 = 22 × 31. Indeed, if a number N can be written as

where

are prime numbers and

then any factor of N can have as its own factors

That is, there are ak + 1 possibilities for the prime number pk.

This is why, for 12 = 2 × 2 × 3 = 22 × 31, the number of factors is (2 + 1) × (1 + 1) = 6.

However, if we allow 1 to be a prime number, how many factors does an arbitrary number have? We wouldn’t be able to count because one person may decide that 1 only appears as 10, while another may say it appears as 123. The first person would determine that 12 has 6 factors, which is correct, while the second would determine that it has 144 factors, which is obviously incorrect.

Precisely because 1 it the multiplicative identity element, it cannot serve the purpose of determining factors because dividing any number of times by 1 does not change the number. Because of this, including 1 as a prime would not just be problematic, but would actually undermine many things we hope to achieve using the theorems of arithmetic. Hence, 1 is somewhat arbitrarily defined not to be a prime number.

A Matter of Choice

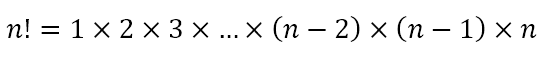

The second example of ‘cooking the books’ arises in the field of combinatorics, dealing with permutations and combinations. One of the most common short forms used in this field is that of the factorial, denoted with the ‘!’ symbol. Here, n! is defined as

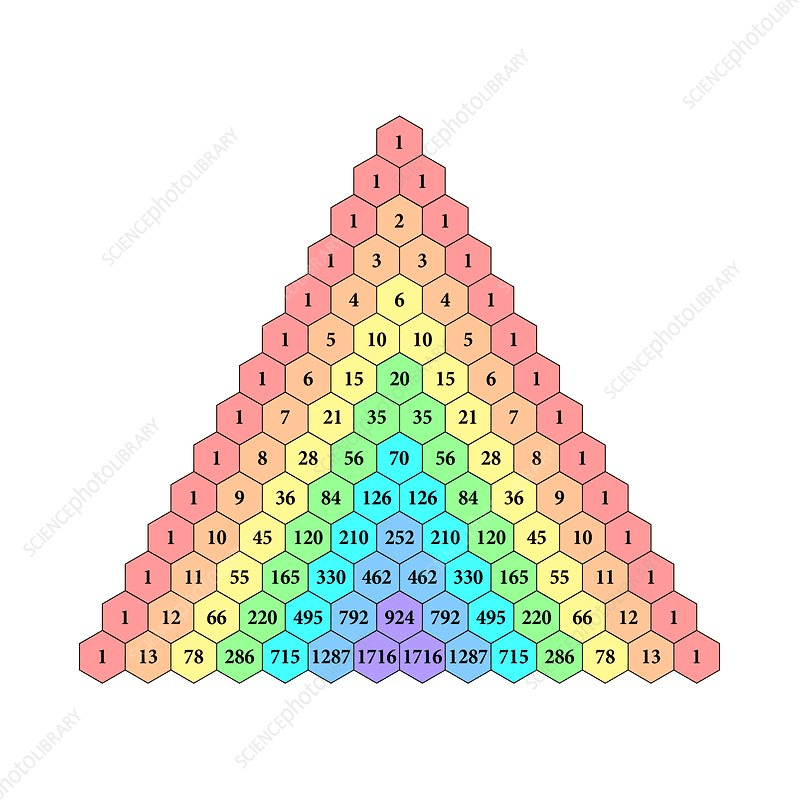

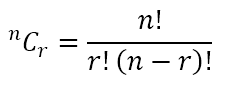

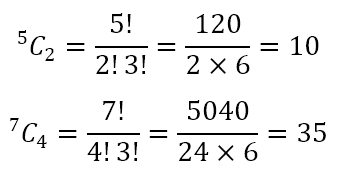

That is, the factorial of n is defined as the product of all the natural numbers from 1 to n. Hence, 3! = 1 × 2 × 3 = 6, 4! = 1 × 2 × 3 × 4 = 24, 5! = 1 × 2 × 3 × 4 × 5 = 120, etc. Now, given n distinct objects, the number of ways of choosing r of them is given by nCr, which is defined as

Hence, we can calculate as follows

an so on. Let us make the above a little more specific, observing the, when we make a choice, the order in which we choose items is irrelevant. Hence, from the set {A, B, C, D, E}, selecting A and then B is the same as selecting B and then A. So, the 10 different selections we can make from the five distinct items A, B, C, D, and E are AB, AC, AD, AE, BC, BD, BE, CD, CE, and DE.

In much the same way, given the seven items A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, the 4 item selections will be ABCD, ABCE, ABCF, ABCG, ABDE, ABDF, ABDG, ABEF, ABEG, ABFG, ACDE, ACDF, ACDG, ACEF, ACEG, ACFG, ADEF, ADEG, ADFG, AEFG, BCDE, BCDF, BCDG, BCEF, BCEG, BCFG, BDEF, BDEG, BDFG, BEFG, CDEF, CDEG, CDFG, CEFG, and DEFG. Hence, as calculated above, there are 35 ways of making 4 item selections from 7 distinct items.

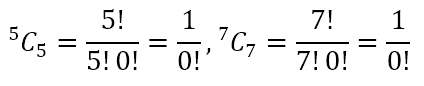

Now, we come to the problem. How many ways are there of selecting 5 out of 5 or 7 out of 7 items? Obviously, the answer is 1. Given the items A, B, C, D, and E, there is only 1 selection, i.e. ABCDE, that contains all 5 items. Similarly, given the items A, B, C, D, E, F, and G, there is only 1 selection, i.e. ABCDEFG, that includes all 7 items. However, what does the formula above give us? Plugging in 5 and 7 into the formula we get

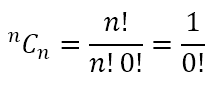

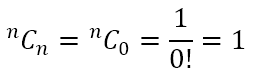

In general, we obtain nCn as

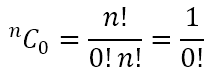

We get the same when we want to select none of the n items because

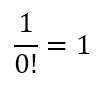

However, the number of ways of selecting no items out of n items is obviously 1, namely the empty set, denoting that none of the items were selected. Hence, we can conclude that

However, the equation

can only be true if 0! = 1. However, this does not align with the definition of the factorial. However, to ensure that nCn and nC0 are meaningful, which they are, and can be meaningfully calculated, we quite arbitrarily define 0! to be equal to 1.

Fits and Starts

What we have seen are two instances in which something that defies a definition is force-fit with a new definition because there are many gains to be had by doing so. Mathematics, while objective for the most part, permits some arbitrariness when the benefits outweigh the losses. Actually, we have seen this earlier in The Quantifiers Strike Back, where we saw that, in order to ensure closure of some operation, we were required to expand the number system. This is something that mathematicians have done for ages. However, every new arbitrary inclusion is often met with opposition. And rightly so. We do not want just about any arbitrary idea to be added on to our edifice of mathematical knowledge. However, through debate and discussion, often including some quite harsh ad hominem attacks, mathematicians slowly get convinced that some ideas are better than excluded. And so, in fits and starts, mathematics, like any other branch of human knowledge, advances.

Leave a comment