The Riddle of the Name

In this post we continue with our study of the conic sections. So far we have looked at the circle, the parabola, and the ellipse. Now we turn to the final non-degenerate conic section – the hyperbola. When we hear the word ‘hyperbola’, some of us may think of the English word ‘hyperbole’ and wonder if the two are related. And indeed they are. The word ‘hyperbole’ is “the use of extreme exaggeration for emphasis or effect.” If we consider the issue of the eccentricity of a conic section, we can see that the circle is one with an eccentricity of 0. The ellipse has an eccentricity between 0 and 1, while the eccentricity of a parabola is 1. Now, the circle and the ellipse are closed figures. However, as the eccentricity becomes larger and approaches 1, the ellipse becomes more elongated and flat. a parabola could be considered a degenerate ellipse where the second focus is actually at infinity, thereby leading to an open figure rather than a closed on. If we choose to ‘throw’ (Greek ballein) in ‘excess’ (Greek hyper) of this limitation, we get a hyperbola. Hence, if we exaggerate the eccentricity beyond that of the parabola, we get a hyperbola. In other words, a hyperbola is a conic section which has an eccentricity that is greater than 1.

Just to refresh our minds about the conic sections, consider the figure above. If the cone is sectioned perpendicular to the axis of the cone, we get a circle. Now, if the sectioning plane is rotated such that the angle made is between being perpendicular to the axis and parallel to the surface of the cone, we get an ellipse. When the sectioning is parallel to the surface of the cone, we get a parabola. And if the sectioning angle is greater than that of the surface of the cone, then we get a hyperbola.

Definition and Basics of a Hyperbola

A hyperbola is the locus of a point which moves such that the ratio of its distance from a fixed point to its distance from a fixed line is a constant greater than one. The fixed point is known as the focus, S and the fixed line is known as the directrix, L. The fixed ratio is the eccentricity, e∈(1,∞), for a hyperbola. A hyperbola actually has two foci, S and S‘, and two directrices, L and L‘, that form two pairs S–L and S‘-L‘ which both satisfy the definition of the hyperbola. The transverse axis of the hyperbola is the line joining the two foci. The vertices of the hyperbola are the points on the hyperbola and its transverse axis. One vertex, A, lies between S and L and the other vertex, A‘, lies between S‘ and L‘. The length of AA‘ is the length of the transverse axis of the hyperbola. The center, O, of the hyperbola is the midpoint of SS‘ (also the midpoint of AA‘). The line perpendicular to the transverse axis through the center of the hyperbola is the conjugate axis. No points lie on the hyperbola and on its conjugate axis. Let us derive the equation of a hyperbola in standard form.

The Equation of the Hyperbola

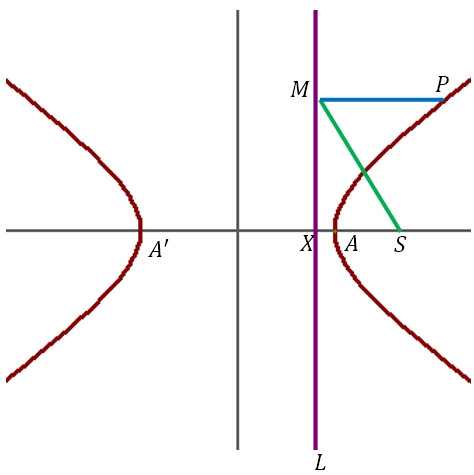

Consider a point, S, given to be the focus of a hyperbola and a line, L = 0, given to be the directrix of the hyperbola. Let e be the eccentricity of the hyperbola. Drop a perpendicular from S onto L and let the foot of the perpendicular be X. Let A divide SX internally in the ratio e:1. Hence, A lies on the hyperbola. Let A‘ divide SX externally in the ratio e:1. Hence, A‘ lies on the hyperbola. Let AA‘ be the transverse axis of the hyperbola. Let O be the midpoint of AA‘, which we take to be the origin of our coordinate system. This is shown in the figure below.

Let OA produced form the positive x axis and let the length AA‘ be 2a. Hence, the coordinates of A are (a, 0) and of A‘ are (-a, 0). Let the coordinates of X be (p, 0) and of S be (q, 0). Then by section formula for internal and external division in the ratio e:1.

This gives ep + q=a(e + 1) = ae + a and ep – q=-a(e – 1)=-ae + a. Adding the two equations we get p = a/e and subtracting we get q = ae. Hence the coordinates of X are (a/e, 0) and of S are (ae, 0) and line L is x – a/e = 0.

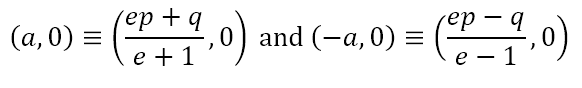

Let P(x, y) be any point on the hyperbola. Let M be the foot of the perpendicular from P onto L. Then the coordinates of M are (a/e, y). Then by definition of the hyperbola SP = e⋅PM.

Let a2(e2 – 1) = b2. Then the equation of the hyperbola becomes

We can observe that the figure is symmetric about both axes. Hence the other focus is S‘ (-ae, 0) and the other directrix is L‘ = x + a/e = 0.

Conjugate Hyperbolas and the Auxiliary Circle

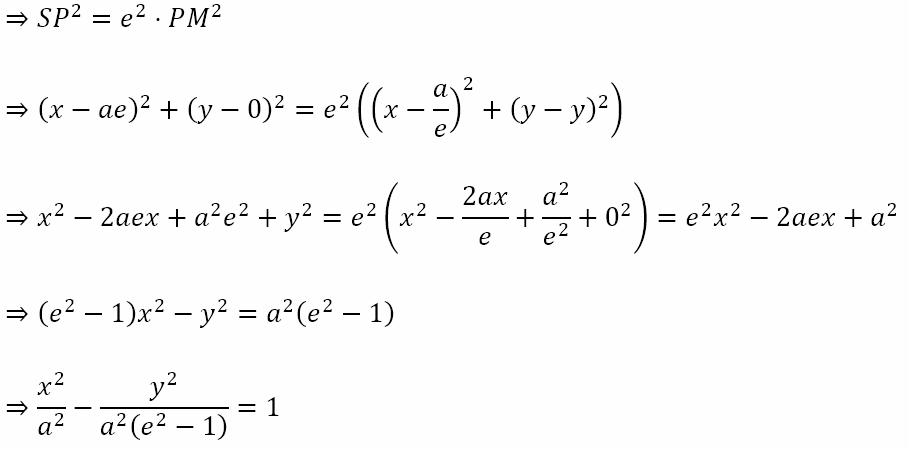

There are two configurations of a hyperbola in standard form depending on whether the constant on the right is 1 or -1, known as conjugate hyperbolas.

Shown in the figure above are the conjugate hyperbolas

The circle with the transverse axis as its diameter is known as the auxiliary circle. For the hyperbola x2/a2 – y2/b2 = 1 its equation is x2 + y2 = a2. For the hyperbola x2/a2 – y2/b2 = -1 its equation is x2 + y2 = b2.

Parametric Coordinates

Consider a point P on the hyperbola x2/a2 – y2/b2 = 1. See the figure on the left below. Let the perpendicular to the transverse axis of the hyperbola (here the x axis) meet the transverse axis at the point Q. Let R be the point of contact of the tangent from Q onto the auxiliary circle. θ, the eccentric angle of P is the angle made by radius OR with the positive x axis. Now OR = a ⇒ OQ= a secθ ⇒y =b tanθ ⇒ P ≡ (a secθ, b tanθ), which are the parametric coordinates of the point on the hyperbola with eccentric angle of θ.

For the hyperbola x2/a2 – y2/b2 = -1, the parametric coordinates are (a cotθ, b cosecθ), where θ is the angle made by the radius formed by the point on the auxiliary circle corresponding to the point P, as shown in the figure to the right above.

Tangent at the Point (x1, y1)

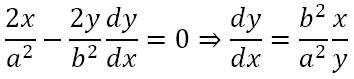

Let us derive the equation of the tangent at a point (x1, y1) on the hyperbola. Consider the hyperbola

Differentiating this equation with respect to x we get

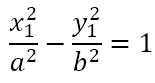

If (x1, y1) is on the hyperbola then

and at the point (x1, y1)

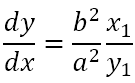

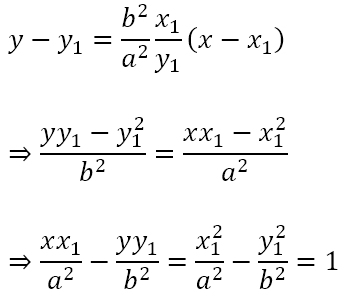

Hence, the equation of the tangent would be

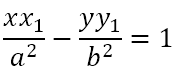

Hence, the equation of the tangent at (x1, y1) is

Tangent at the Point (a secθ, b tanθ)

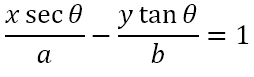

Since the point (a secθ, b tanθ) satisfies the equation of the hyperbola, the equation of the tangent at the parametric point will be

Condition for Tangency

Consider the line y = mx + c and the hyperbola

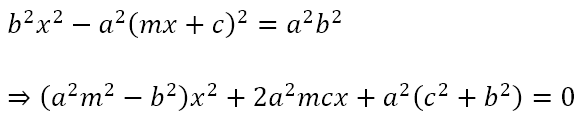

Solving the two equations we get

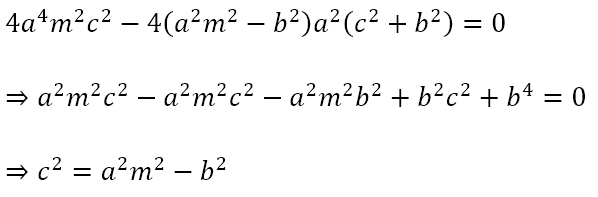

If the line is a tangent to the hyperbola, the above quadratic equation should have a repeated root, meaning that its discriminant must be zero. Hence,

Hence, we can conclude that the line

is always a tangent to the hyperbola

The Return of the Riddle

We have seen some interesting things about the hyperbola. There are many similarities between it and especially the ellipse. For example, the equations in standard form only differ in the sign (+ or -) that separates the terms. Similarly, both figures have a well defined auxiliary circle. Further, both conics have trigonometric parametric coordinates, though obtaining them for the hyperbola took a little more creativity than for the ellipse. This was primarily because the ellipse is easily visualized as a squashed circle, while the hyperbola, with its twin branches makes visualization a little more difficult. Indeed, it is because the eccentricity is ‘exaggerated’ (i.e. greater than 1), that the distance from the focus expands more rapidly than the distance from the directrix, making it impossible for the point to come back down toward the transverse axis to close the figure. In other words, the value of the eccentricity leads to the ‘excess’ (hyper) throwing (ballein) of the point, thereby yielding the hyperbola.

I will be taking a break next week. Hence, the next post will be on 7 November. In that post we will look at some more properties of the hyperbola, including the chord of contact and the polar. If you have forgotten what those words mean, please refer to Contacting Circular Polarity. And may you not experience any exaggerated hurling! Make of that what you will!

Leave a comment