Making the Case

We are in the middle of a series of posts on conic sections. After the introductory post, Finding Refreshment in the Desert, I devoted three posts to the circle and two each to the parabola, ellipse, and hyperbola. In the previous post I had mentioned a degenerate conic section known as a pair of lines. I know this doesn’t have the same kind of ring to it as do the others. But then, this is a degenerate conic section we are talking about. Many mathematicians do not consider it legitimate to include it among the regular conic sections. However, if we have included the circle, which is a degenerate ellipse, then I do not see why a degenerate hyperbola should not be included! Further, if a conic section is the curve obtained by sectioning a cone with a plane, then we can easily recognize that sectioning the cone through its apex will yield a shape that is actually two lines that intersect at the apex. Hence, I hold the view that the pair of lines is a valid conic section and should be studied under that umbrella.

Joint Equation of Lines Through the Origin

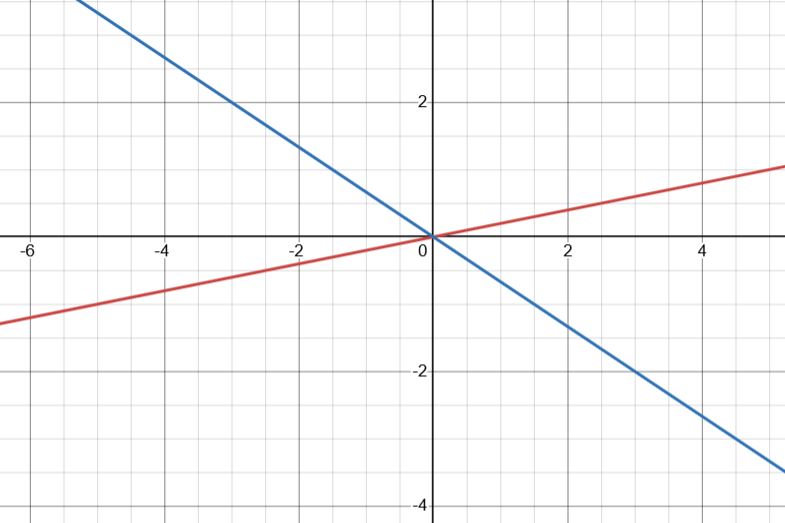

Our study of the pair of lines begins with a single line through the origin. Its equation will be y = mx. This means that m = y/x, which gives us the slope/gradient on the line. We can also write this as y – mx = 0. Any point on the line will satisfy its equation. We make the following observations: 1. the line passes through the origin; 2. the slope/gradient of the line is m.

Now consider two lines y – m1x = 0 and y – m2x = 0. Let us consider the equation (y – m1x)(y – m2x) = 0. The represents the product of two numbers given by y – m1x and y – m2x. The equation states that this product is zero. However, the product of numbers can be zero if and only if one of the numbers is zero. This must mean that either y – m1x = 0, meaning that we have a point on the first line, or y – m2x = 0, meaning that we have a point on the second line. In other words the equation (y – m1x)(y – m2x) = 0 represents points that lie on either of the two constitutive lines. We call this equation the joint equation of the lines.

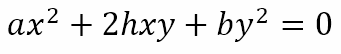

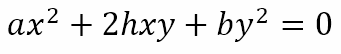

If we expand the product, we will obtain a second degree equation that has the form

If we divide this equation by x2, we will obtain

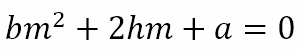

Now recall that m = y/x. Hence, replacing y/x with m we get

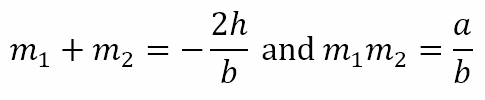

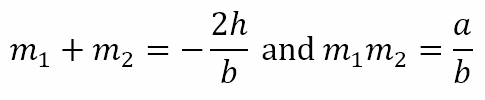

This is a quadratic equation in m and should have two solutions m1 and m2. From what we know about the sum and product of the roots of quadratic equations, these solutions satisfy the two equations

So we have y/x = m1 or y/x = m2, both of which are straight lines through the origin. It follows that every second degree homogeneous equation in two variables represents the joint equation of two straight lines through the origin.

Angle between the Lines ax2 + 2hxy + by2 = 0

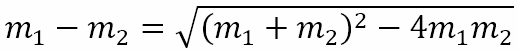

Let the lines make angles of θ1 and θ2 with the positive x-axis. Then m1 = tan θ1 and m2 = tan θ2, where

If θ is the acute angle between the lines then

Now, we know that

Using the equations for the sum and product of the slopes/gradients we get

Nature of the lines ax2 + 2hxy + by2 = 0

We just derived

From this we can conclude that, if h2 – ab > 0, we have two real and distinct lines, if h2 – ab = 0, we have two real and coincident lines, and if h2 – ab < 0, we have two imaginary and distinct lines. Further, if a + b = 0, we have two real and distinct perpendicular lines. It is crucial to note that in all cases the two lines pass through the origin – a real point! This is because zero is both real and imaginary!

Joint Equation of General Pair of Lines

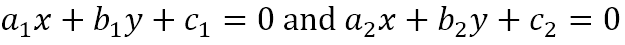

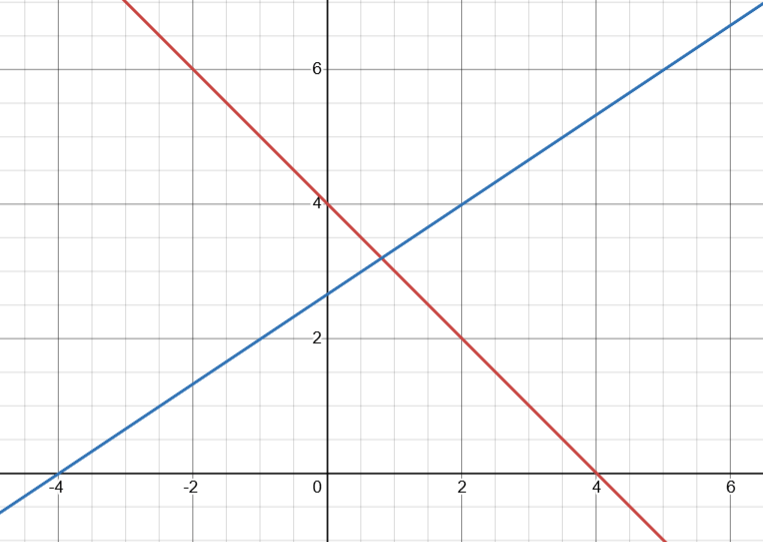

Of course, we have only considered lines through the origin. What about lines in general? Let us consider the two lines

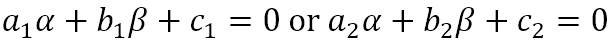

Let P(α, β) be a point on either of the lines. Then either

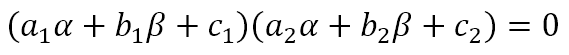

This means that the product

Hence, the equation

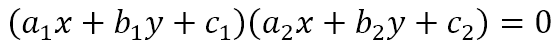

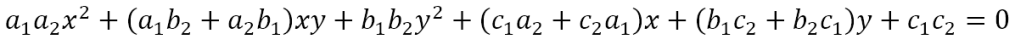

represents points that lie on either of the two lines. In other words, it is the joint equation of the two lines. Expanding the brackets we get

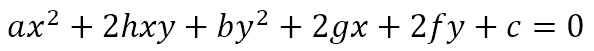

This is of the form

which is a general second degree equation in two variables. However, while this means that the joint equation of two lines is always a second degree equation in two variables, it does not mean that every general second degree equation in two variables represents a pair of lines.

Now recall, from Finding Refreshment in the Desert, that the general second degree equation in two variables was obtained by sectioning a cone with a plane. If the pair of lines is a genuine conic section, then its equation should also satisfy the condition of being a general second degree equation in two variables. Of course, the equation

satisfies the condition with g = f = c = 0. However, this represents only straight lines through the origin. What about straight lines that do not pass through the origin?

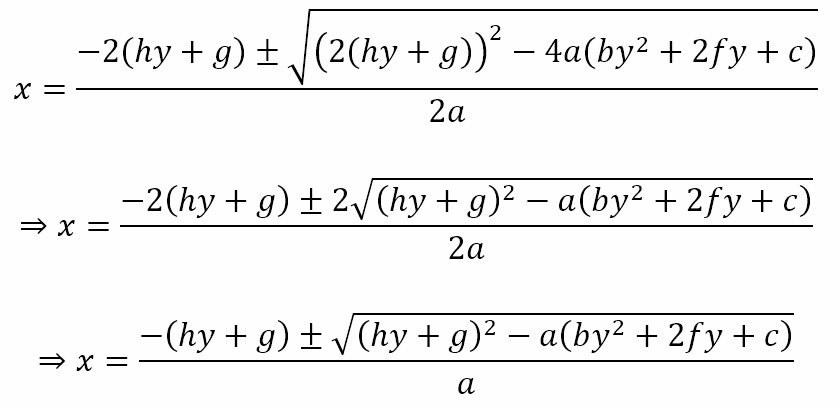

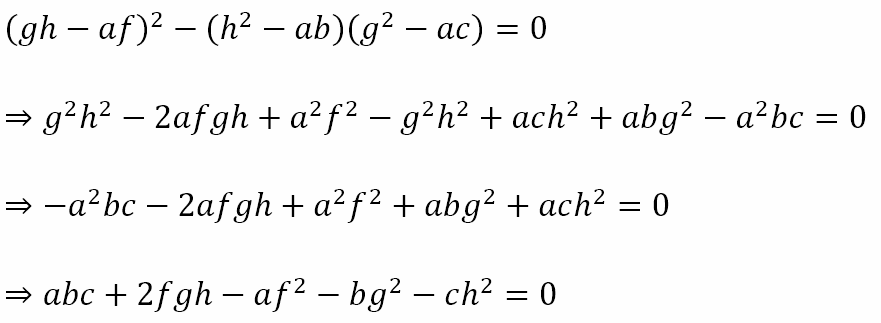

If the general second degree equation in two variables represents a pair of lines then the LHS of the equation can be factorized into two linear factors. If we treat the equation as a quadratic equation in x we obtain the solutions for x as

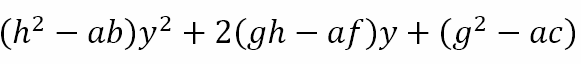

If we have two linear factors then the quantity under the root must be a perfect square. The quantity under the root is

For this to be a perfect square, its discriminant should be zero. Hence,

When the above condition is satisfied, the general second degree equation in two variables represents a pair of lines. Hence, we can conclude that the pair of lines is a genuine conic section since the general equation representing a conic section under certain conditions represents a pair of lines. What about when the condition is not satisfied? What can we say then?

Conditions on ∆ and h2 – ab

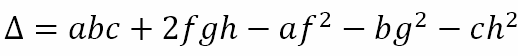

Let us define

We have seen that, when ∆ = 0 the general second degree equation in two variables represents a pair of lines. We also saw earlier, the conditions for real and imaginary pairs of lines. We can collate this along with what we know about the other conic sections to obtain the table below.

Of course, it will not do for me to just give you the final conclusions. We have derived the conditions for ∆ in this post. However, the conditions for the other conic sections can also be derived. Since this does not directly relate to the pair of lines, and because the derivation involves some serious algebraic juggling, those who are curious can view the derivation here.

The Way Ahead

I think in this post I have made the case for considering the pair of lines as a genuine conic section. I do not know why they are often excluded from the study. However, if the circle, which is a degenerate ellipse with eccentricity of zero, is included, why should the pair of lines, which is a degenerate hyperbola with and infinitely large eccentricity, be excluded? I think it is only because we are familiar with the circle from early years in school and are never taught to consider multiple lines together without aiming to solve them simultaneously to obtain their points of intersection. And since that is something that is often taught, in the next post we will consider how to use the general second degree equation in two variables to obtain the point of intersection (if it exists) of the two lines. We will also look at a procedure known as homogenization. Curious? Stay tuned!

Leave a comment