The Final Spur

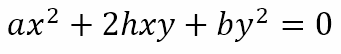

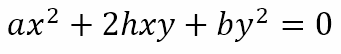

For some weeks now, we have been focusing on the conic sections. In the last post, A Mathematical Straight Couple, we introduced the pair of lines as a degenerate hyperbola. We saw that the joint equation of a pair of lines through the origin is

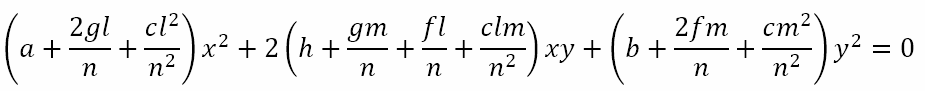

This kind of equation, where the sum of the powers of the variables in each term is the same and the constant term is zero is known as a homogeneous equation. However, the general second degree equation in two variables, which is

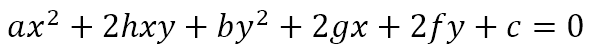

is not a homogeneous equation. For this equation, in the previous post, we defined

and we showed that if ∆ = 0 the general second degree equation in two variables represents a pair of lines. In this post, I wish to look at determining the point of intersection of a pair of lines described in the form of the general second degree equation in two variables and to look at another concept known as ‘homogenization’.

Transformation of Coordinates

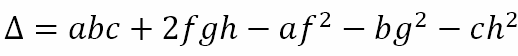

Before we can determine the point of intersection of the two lines, we need to learn about transformation of coordinates. Suppose we have a point A(x, y) according to a previously defined set of rectangular axes. Now suppose we move the origin and the axes (with translation only, no rotation) to the point (p, q). It is evident that the coordinates of all points on the plane will change. Suppose the new coordinates of A are (X, Y). This is shown in the diagram below.

From the diagram above it is clear that X = x – p and Y = y – q. Hence, when we move the axes p units to the right and q units up, the new x and y coordinates, indicated by capital letters in our convention, are reduced by p and q respectively.

The Point of Intersection of the Lines ax2 + 2hxy + by2 + 2gx + 2fy + c = 0

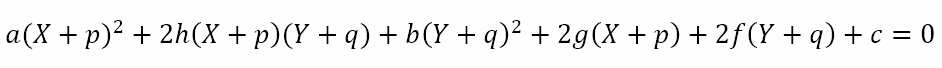

Suppose the equation ax2 + 2hxy + by2 + 2gx + 2fy + c = 0 represents two straight lines and that their point of intersection is (p, q). Now, if we shift the origin to the point of intersection, we should get a homogeneous equation in the new coordinates because the lines now pass through the new origin. From what we know about transformation of coordinates X = x – p ⇒ x = X + p and y = Y + q. Making these substitutions we get

Grouping terms according to degree and variable we get

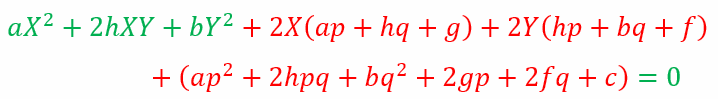

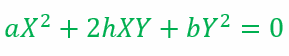

If this is a homogeneous equation it must reduce to

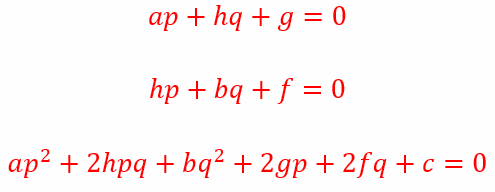

Then we must have

Now since (p, q) is the point of intersection of the lines, the coordinates must satisfy the joint equation of the lines. Hence,

Hence, the third equation above is automatically satisfied by the point of intersection of the two lines. Solving the equations ap + hq + g = 0 and hp + bq + f = 0 simultaneously we get

which gives the coordinates of the point of intersection.

Coincident and Parallel Lines

Recall, from the previous post, that the angle between the lines

is given by

It is clear that, if h2 – ab = 0, then the angle between the lines is 0°, meaning that the lines are either coincident or parallel. In that case, there will be infinitely many points common to the two lines or no points in common. Hence, we can say that, if ∆ = 0, h2 – ab = 0, bg – hf = 0, and af – gh = 0, then the lines are coincident. Also, if ∆ = 0, h2 – ab = 0 and either bg – hf ≠ 0 or af – gh ≠ 0, then the lines will be parallel.

Homogenization of a Curve with a Line

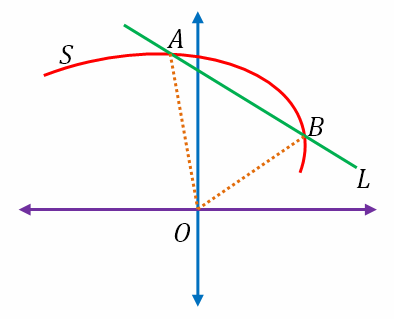

Suppose we have a curve S = ax2 + 2hxy + by2 + 2gx + 2fy + c = 0 and a line L = lx + my – n = 0. These are shown in the figure below in red and green respectively.

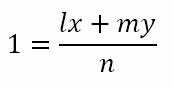

Let the line and the curve intersect at A and B as shown. It is evident that the coordinates of A and B satisfy the equations of both the curve and the line. Hence, A and B satisfy any combination of the two equations. Suppose we write the equation of the line as

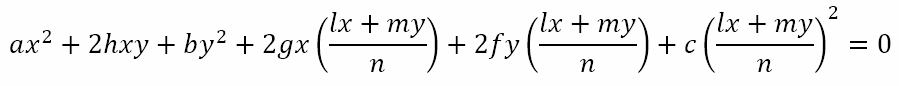

This is true for points A and B. Hence,

holds at points A and B. Hence,

However, this last equation is a second degree homogeneous equation in two variables and must represent two straight lines through the origin O that also pass though points A and B. Hence, this last equation represents the joint equation of the lines OA and OB.

Now, the concept of homogenization might seem to be strange and perhaps even difficult to use. So, let us actually use it to solve a problem.

Using Homogenization

Let us prove that chords of the parabola y2 = 4ax which subtend a right angle at the origin pass through a fixed point. Note that what follows is a standard 4-step approach to problem solving, which I hope will help some of the readers since it works in pretty much every area of life and not just mathematics!

Step 1: Information collection

Given the parabola y2 = 4ax. Let the chord be lx + my – 1 = 0. We have to prove that if the chord subtends a right angle at the origin then it must pass through a fixed point.

Step 2: Conceptual plan

If we homogenize the equation of the curve S = y2 = 4ax with the equation of a line L = lx + my – 1 = 0 then we obtain the joint equation of the lines joining the origin to the points of intersection of the curve S and the line L. Further, the lines ax2 + 2hxy + by2 = 0 are at right angles to each other if a + b = 0.

Step 3: Execution

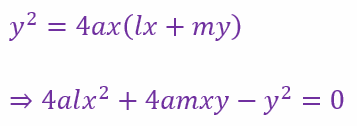

Homogenizing with the equation of the parabola we get

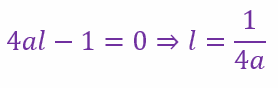

This represents a pair of lines through the origin. If the lines are perpendicular to each other

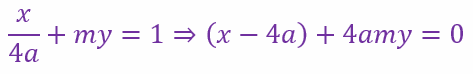

Hence, the line is

where m is a parameter. This represents a family of lines all of which pass through the point of intersection of the lines x – 4a = 0 and y = 0. But the point of intersection of these two lines is (4a, 0). That is, the chord passes through the point (4a, 0)

Step 4: Verification

The working is correct and we have proved what had to be proved. And note that we did not even need to know that y2 = 4ax is a parabola!

Journey’s End

As we wrap up this series on the conic sections, we can observe that we have covered quite a bit of ground. We have looked at the geometric definition of a conic section as the curve formed when a cone is sectioned by a plane. We have also defined it in terms of coordinate geometry, using the focus, directrix, and eccentricity. We have derived the equations for the conic sections in standard form and have also derived the parametric coordinates of any point on the conic section. We have obtained the equations of the tangents at a point on the conic section in terms of Cartesian coordinates and parametric coordinates. We also introduced the idea of the chord of contact, the pole, and polar of a point in relation to a conic section.

Along the way, we introduced the idea of degeneracy for a conic section and saw that the circle was a degenerate ellipse with eccentricity of zero. I defended the idea of including the pair of lines among the conic sections as a degenerate hyperbola with an infinite eccentricity. In this context, we looked at the conditions under which the general second degree equation in two variables represents a pair of lines. Then we obtained the point of intersection of a pair of lines and conditions for perpendicularity and parallelism of a pair of lines. Finally, we looked at the idea of homogenization, which we used to prove an important property of the parabola.

Unfortunately, our journey into the world of the conic sections has come to an end. I hope it has been as enjoyable for you as it has been for me. I will be taking a break for a week and will resume on 5 December 2025. Till then, stay eccentric!

Leave a comment