Importance of Calling a Spade a Spade

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/52789493/SH3_Ep2rel_5.0.jpg)

Ok, ok! Don’t get all wound up with the title of this post. There will be no kidnapping involved. Nor will any of you be held for ransom. It’s just that I think sometimes mathematicians seem to have some strange inclination for choosing terminology that will shoot them in the foot! Abduction? I mean, come on! People already have a fear of the subject and you tell them you will be engaging in abduction?! I will devote a post at a later date to unfortunate mathematical terminology.

But actually, the mathematical term ‘abduction’ is derived from the now obsolete verb ‘to abduce‘, which means, “bear witness, evidence, testify, prove, show.” It is lamentable that the supposedly more authoritative dictionaries like Oxford English Dictionary and Merriam-Webster Dictionary do not have the obsolete meaning listed anymore. Anyway, from the preceding it is clear that mathematical abduction would be the process of bearing witness or testifying or proving.

Now, most people would know that mathematics and logic are closely related. Unfortunately, some quite lax use of mathematical terminology has led to common misunderstandings of the mathematical processes involved in mathematical reasoning. One of the prime culprits, in my view, is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who has the detective Sherlock Holmes claim that he solves cases by a process of deduction. As can be seen at the 3:30 mark in this video, though Sherlock guesses that ‘Harry’ is Watson’s brother, Watson reveals that ‘Harry’ is short for ‘Harriet’, his sister. Keep this in mind as we discuss a few strategies for mathematical reasoning.

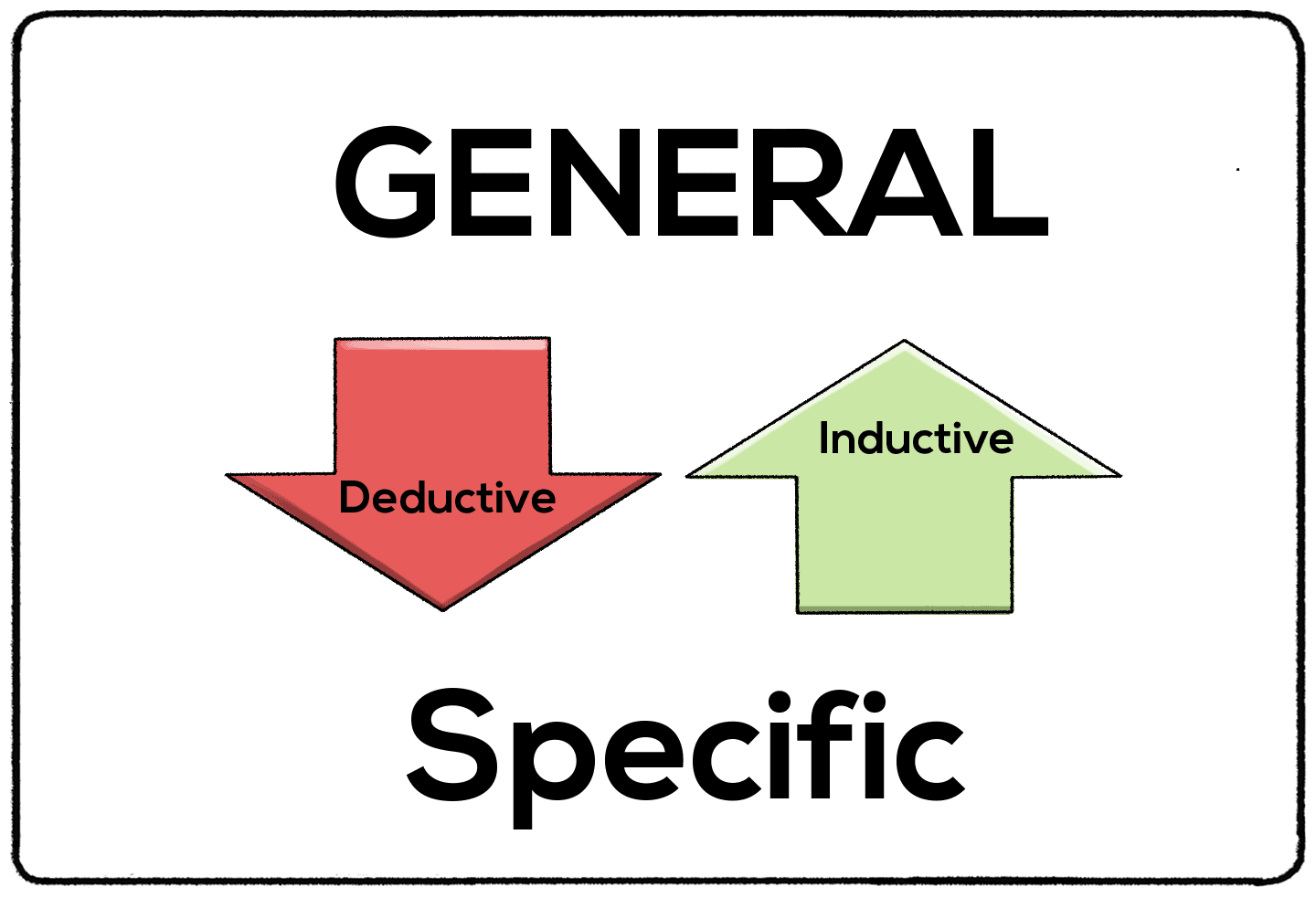

Mathematical reasoning is done through logical arguments. Sound mathematical reasoning will reflect impeccable logic. Logical arguments can be broadly grouped into three approaches – deduction, induction, and abduction. Most of us are not formally introduced to the third, which is the main focus of this post, even though it is one of the main ways in which we make sense of the world. But let me briefly explain the first two approaches so we have some idea of what we are talking about before dealing specifically with abduction.

Deduction – From the General to the Specific

Deduction is a logical strategy by which we use logical consequences to make our arguments. So, for example, we might reason as follows:

Major premise: All mammals are vertebrates

Minor premise: Dogs are mammals

Conclusion: Dogs are vertebrates

The validity of the conclusion is guaranteed here by the validity of the premises. If it is true that all mammals are vertebrates (it is) and if it is true that dogs are mammals (it is), then it follows that dogs are vertebrates.

Of course, if one of the premises is false, then the deductive reasoning breaks down. For example:

Major premise: All mammals are invertebrates

Minor premise: Dogs are mammals

Conclusion: Dogs are invertebrates

Here it is clear that the major premise is incorrect, leading to an incorrect conclusion. However, we could have the following line of reasoning:

Major premise: All reptiles are vertebrates

Minor premise: Dogs are reptiles

Conclusion: Dogs are vertebrates

Here a correct conclusion has been reached through incorrect reasoning since the minor premise is false. Hence, even though the conclusion that dogs are vertebrates is correct, we must conclude that the deductive reasoning actually has failed. Deduction depends on a strict order. Consider the following example:

Major premise: All mammals are vertebrates

Minor premise: Dogs are vertebrates

Conclusion: Dogs are mammals

While all three statements are true, the conclusion actually does not follow from the premises because the group in the conclusion is a subset of the group in the minor premise. However, if we order things carefully, deduction can be quite airtight. In that case, granted that both premises are correct, it logically follows that the conclusion is correct. However, we can identify a weakness in deduction from the following example:

Major premise: All humans are mortal

Minor premise: Sherlock is a human

Conclusion: Sherlock is a mortal

Once again, if the major and minor premises are true, the conclusion must follow. However, the ‘Sherlock’ I refer to may be my dog (threw a curveball, didn’t I?), in which case, while it is true that ‘Sherlock (my dog) is mortal’, it does not follow from the premises because the minor premise now is false. What happened here is not that deductive reasoning failed per se, but an indication of how important it is for terms to be carefully defined. The statement ‘Sherlock is a human’ is not clearly defined because of the inherent ambiguity in the word ‘Sherlock’, which could be a name of a dog also, as it is in this case. This would fall into the category of the ‘ambiguous middle term’ fallacy. It is not a failure of the strategy of deductive reasoning but a failure to use terms in an unequivocal manner.

Reasoning in mathematics mostly follows the deductive model, which is why mathematical arguments tend to be pretty airtight. This reliability is amplified by the fact that mathematical elements are clearly defined. Unlike in the case above where the middle term ‘Sherlock’ was ambiguous, mathematical elements admit to no such ambiguity.

Induction – From the Specific to the General

Induction, on the other hand, is an approach to reasoning that generalizes from a few cases. This approach, however, is common in the areas of science and humanities. For example, when someone proposes a scientific law, e.g. Ohm’s law, it is based on some empirical data. While the data set might be large, no data set could encompass all the possibilities. Hence, the scientist is forced to generalize about some universal ‘law’ from the data that is available. For example, an ornithologist might reason as follows:

Major premise: Every swan I have seen happens to be white.

Minor premise: I have seen hundreds of swans.

Conclusion: All swans are white.

While this generalization might be understandable, the conclusion is incorrect, since there are black swans.

As another example, the admissions officer in a university looks at the GPA of students graduating from her university and notices the following:

Major premise: All the top 10% of the graduates had a high school GPA greater than 3.5.

Minor premise: The sample includes thousands of students.

Conclusion: Students with a high school GPA greater than 3.5 become the top 10% of college graduates.

Of course, we know of exceptions. There are students with low high school GPA who have excelled in college and vice versa.

As we can see, even if the premises are true (i.e. all swans I have observed have been white and I have seen hundreds of swans or all the top 10% college graduates had a high school GPA greater than 3.5 and she has sampled thousands of students), the conclusion is not mathematically warranted. This is because a universal claim, which is involved in the process of generalization, requires only one counterexample for the claim to be shown as false. Other disciplines are ok with proceeding with such reasoning since they are willing to change their premises and conclusions based on new evidence. However, unless the process of induction actually covers all possible cases, an impossibility in the sciences and humanities, mathematics will not accept it as proof.

This is precisely why the unfortunately named process of mathematical induction is a valid method of proof, because the inductive argument actually exhausts all possible cases. I will devote a future post to discussing this brilliant strategy.

Unfortunately, the mathematically lax approach of the sciences and humanities, in that they are willing to accept non-exhaustive inductive arguments, has infected the study of mathematics. In my years as a teacher, I have found that students often make inductive arguments while thinking that they are making deductive ones. So for example, if asked to prove that the sum of the first n natural numbers is n×(n+1)÷2, they may give examples like:

The sum of the first 2 natural numbers is 1+2=3 and 3=2×(2+1)÷2.

The sum of the first 3 natural numbers is 1+2+3=6 and 6=3×(3+1)÷2

And so on. They may give dozens and dozens of examples and think that they are actually proving something. However, since induction can be falsified with only one counter example, this approach actually does not prove anything because it could well be that the next number breaks the mold.

Abduction – From Data to the Best Explanation

The third strategy of mathematical reasoning is abduction. Abduction is a strategy of logical reasoning in which a given set of data is used to draw an inference to the best explanation for the data. Abduction involves not just consequence, as in the case of deduction, but also causation. But more importantly, abduction goes in the reverse direction of deduction. Remember, deduction proceeds as follows:

Major premise: If A is true, then B is true.

Minor premise: A is true

Conclusion: B is true

Let me explain this in the case of the first example of deduction given above.

Major premise: If an animal is a mammal (A), then the animal is a vertebrate (B)

Minor premise: I have an animal, a dog in this case, which is a mammal. Hence, A is true.

Conclusion: B is true. Hence, the animal is a vertebrate.

Abduction works in the reverse direction. Hence, if the proposition, if A is true, then B is true, abduction infers A if B is true. In other words, abduction would go as follows:

Major premise: If an animal is a mammal (A), then the animal is a vertebrate (B)

Minor premise: An animal is a vertebrate. Hence, B is true.

Conclusion: The animal is a mammal.

It is easy to realize the abduction does not necessarily lead to a truthful conclusion. In this case, since most vertebrates are not mammals, it is highly presumptuous to conclude that a vertebrate must be a mammal. But perhaps a better example of abduction might help understand why it is one of the most powerful methods we use.

Suppose I am at a pool bar. When I turn toward the pool table I notice the cue ball heading toward one of the other balls. I can abduce that the cue ball was hit with the cue stick. That would be the most probable explanation. However, a number of other explanations may be true. It could well be that a player illegally moved the cue ball with his hand. Or it could be that a player accidentally hit one of the non cue balls, which then hit the cue ball, thereby setting it in motion. Or it could be that the cue stick hit the cue ball, which then hit another ball, thereby coming to rest. The other ball now bounces off the wall and hits the cue ball, thereby setting it in motion again.

So you can see that there are a number of explanations for why the cue ball is heading toward one of the other balls. Each of them would have a certain probability associated with it. But, in the context of a game, it is most likely that the cue ball is set in motion by the cue stick. Hence, while my abduction cannot give me certainty, it can tell me what is most likely the case.

Holmes’ Surreptitious Bait and Switch

Coming back to Sherlock Holmes, it is easy to see that he is not engaged in the process of deduction, but of abduction. He makes some observations (see the entire video cited earlier) and draws some inferences about what might have caused what he observes. He works in the realms of probabilities, choosing those explanations that have a higher probability. If he were engaging in deduction, then there would have been no way he could have reached the wrong conclusion that ‘Harry’ was Watson’s brother because, as we have seen, deduction is airtight once you have clearly defined terms and clearly ordered premises and conclusions.

Abduction is what most of us engage in the majority of the time. We make observations and attempt to determine the most likely explanation for the situation. Unlike deduction, abduction depends on probabilities. As we saw in the case of the cue ball on the pool table, the most likely explanation is that the ball was hit by the cue stick. However, the process of abduction does not allow for an airtight conclusion. This is where Doyle’s use of the word ‘deduction’ to characterize Holmes’ method proves to be confusing. Indeed, this confusion spills over to other areas of life, sometimes with disastrous results, as we will see.

I have claimed that we engage in the process of abduction a lot. In fact, when we do not have the full picture but only some present set of conditions, we are left with the necessity of making a hypothesis that could explain the current situation. And since we most often do not have the full picture, abduction becomes the only tool we can use to reach some idea of the causes for the present condition. Actually, it is impossible to have the full picture because the full picture will involve too many factors across too vast a period of time, rendering us incapable of making even an initial hypothesis.

This is the irony of life. The less information we possess, the less accurate will be our hypothesis. However, the more information we possess, the more difficult it becomes to sort through the information and decide which of the factors is (are) most likely the cause(s) for the current situation.

Hippocratic Abduction

This is especially true in the area of medicine. Our bodies are a fabulous complex of highly interrelated systems. What happens to one part of the body can have devastating and at times unpredictably devastating consequences for another part of the body. With the advance of medicine, we have at our disposal more information than we ever had before. However, precisely because we have so much, often counter-indicative, information, making an accurate diagnosis becomes difficult.

However, even when the diagnosis is not inordinately difficult, since we are working with abduction, any hypothesis that is made carries with it an associated probability. Even in the case of a very highly likely diagnosis, the interplay between different parts of the body during treatment is uncertain. In most such cases even the associated probabilities might be lacking, making the final treatment plan only a best guess.

But this is not what we want from our doctors. We want certainty because the life of a loved one may be on the line. And since Holmes keeps calling his method ‘deduction’ we believe that doctors can also engage in a similar process of deduction. Further, since mathematical deduction is a fool-proof strategy of reasoning, we assume that the doctors will also be able to give us a fool-proof diagnosis and treatment plan.

But then there are times when we see the doctors themselves grasping at straws because they are seeing something that is either so rare that it is outside their own experience or so rare that it has not even been documented. In such situations, while they may still be engaged in the best reasoning that can be done, there will be too many factors for any reasonable or reliable abduction to happen. Yet, we still function under the false assumption that the doctors are actually engaged in deduction.

Farewell to Certainty

So we can see that abductive reasoning is not some esoteric skill that few of us possess. Rather, it is something that is valuable in almost every area of life where we are forced to make decisions on the basis of limited knowledge. Automobile repair, classroom teaching, economic policies, interior design, legal proceedings, political treaties, war strategies, etc. are all areas in which abduction is crucial. Indeed, one cannot excel at any of these fields without engaging in abduction.

In other words, though we live in a thoroughly probabilistic world, most of us operate under the fiction that the world is deterministic. Hence, we think that the cause of a situation we find ourselves in is always available to those with adequate knowledge. Ironically, the experts in each of these fields encourage the majority of us to hold such fictive views. After all, in most cases, their abductive reasoning will be borne out as sound. They will appear to us as magicians who have just made our problems disappear or who have just conjured a solution to our problems from an invisible hat.

But when things go wrong, that is when we realize that none of the experts were actually using the fool-proof method of deduction that we thought they were and that they encouraged us to think they were using. Rather, then, as the pieces fall around us, we realize to our horror, that they were using the probabilistic method of abduction that had failed them in our case.

Note, however, that the experts do not choose to not use deduction. If they were able to use deduction, they would, because deduction is a far easier strategy of mathematical reasoning. However, for the most part, life does not place us in situations conducive to deduction. More to the point, deduction cannot be used after the fact, contrary to Holmes’ claims. When we want a post hoc line of reasoning, the only thing available is abduction with its inherent weaknesses.

The ubiquity of abduction leads us to understand that the world is not as cut and dry as we would like it to be. Indeed, mathematics itself, often considered to be a rigid subject that grants unprecedented certainty, allows us to realize that certainty is a pipe-dream. In fact, when we understand the probabilistic nature of abduction, we are liberated from the straitjacket of certainty into the freedom of a world we cannot control. And we are then encouraged to hold everything lightly rather than in a vice-like, and often soul-crushing, grip.

Leave a reply to Absurdities to the Rescue – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply