Numerical Predicament

Numbers are one of the first things we are introduced to in our lives. It is quite likely that our parents introduced us to them, either when reading a book to us or when helping us play with some kind of toys. Very soon after this we are introduced to the idea of performing operations on numbers. And this takes on a more formal shape when we enter school.

Along the way we are introduced to different kinds of numbers – natural or counting numbers, whole numbers, integers, fractions or rational numbers, irrational numbers, real numbers, and finally complex numbers. And we learn how to perform the various operations with these numbers.

However, none of my teachers ever bothered to tell me why we keep expanding the set of numbers, what is gained by doing so, and crucially what is lost in the process. Moreover, in my career spanning over three decades now, there have been only a handful of students who have been able to suggest an answer to a simple question: “In what context or contexts do you think the need for integers arose?”

To ‘Zero’ and Beyond

Of course, we have no access to the actual events that precipitated the conceptualization of integers. But we do possess quite active imaginations. And most of us have been given at least a whistle stop tour of human history from the emergence of our ancestors from Africa to the twenty-first century. So we know that there was a time when we were hunter-gatherers. We know that currency is a recent development.

Hence, we could imagine a situation in which two hunter gatherers went out one day to gather fruit. One gathers a bounty, while the second comes back empty handed. Right away the idea of ‘zero’ or ‘nothing’ had formed in the mind of the second.

Here, I request the reader to allow me a short diversion. One thing that really bugs me is the ubiquitous repetition of the idea that some Indian (Ramanujan or Brahmagupta, take your pick!) invented or discovered zero. Absolute balderdash! At best we can claim that this is the earliest written evidence we have for the use of zero as a numeral. The idea of ‘nothing’ would have formed in our ancestors’ heads long before we had devised any writing systems. Or are you telling me that the second gatherer above actually did not realize he had returned with nothing, that his hands were as empty as when he began his search? This strains all credulity and it really is a wonder that we still have such nonsense spouted even by well meaning mathematics teachers, who ought to know the difference between the idea of zero and the numerical representation of zero.

This is not to disparage the invention of the numeral for zero as a placeholder. That was indeed ground breaking. The power of modern mathematics depends largely on the invention of the place value system, without which we would still be writing things like XLIV plus XXXIX equals LXXXIII, with no idea of how the ‘I’s, ‘V’s, ‘X’s, and ‘L’s related to each other! And without the numerical placeholder for zero we would still not know the difference between eleven (11), one hundred one (101), and one thousand one (1001), all being written as 11! So I do not wish to deny the ground breaking invention of the numeral for zero, while also holding on to the difference between the numeral and the number, ideas that, unfortunately, none of our dictionaries are able to spare from conflation!

Anyway, coming back to our unsuccessful gatherer, since he is starving, he asks the other for some of her fruit. She gives him a few baobab fruits with the understanding that she wants them back. Hence, when he goes out next, the first few baobab fruits actually belong to his creditor! His indebtedness to her meant that she would ‘take away’ some of the baobab fruits he gathered on his next foraging trip before he could enjoy the rest. And voila! The idea of negative numbers is born!

Note that this does not mean that the two gatherers sat down and developed all the rules for adding, subtracting, and multiplying with negative numbers! They would likely have addressed it with an understanding of who owed whom how many baobab fruits.

But if we stopped to think about the incursion of these new-fangled numbers, we will see that they were needed as soon as we decided that there would be a ‘taking away’. In other words, as long as we were only ‘incrementing’ (i.e. adding) there was no need to postulate the existence of any ‘negative’ numbers. But as soon as we introduced the possibility of ‘taking away’ (i.e. subtraction) the counting numbers were rendered insufficient.

Of course, we can recognize a huge gain in introducing negative numbers. Earlier, subtraction of two numbers did not ensure that we would get a number. For example, what would 2 – 5 be equal to? If we did not have the idea of negative numbers we would not be able to evaluate this simple expression. But with the introduction of negative numbers we can.

However, we have lost something, right? What we have lost is a ‘starting point’. Earlier, if we considered the numbers 1, 2, 3, etc. or even 0, 1, 2, 3, etc., we knew where to start counting. But with the set of integers there is no ‘starting point’. While this may seem an insignificant loss compared to what is gained, this is precisely my point! Mathematics is not an area of knowledge that is unconcerned with benefits and costs. It is precisely because what is gained outweighs what is lost that mathematicians have decided that it is prudent to include negative numbers.

Of course, someone may propose listing the integers as 0, ±1, ±2, ±3, etc. While this gives us a ‘starting point’, we have lost any idea of arrangement. That is, given two random numbers p and q, there is absolutely no way of telling before hand if the pth number in this sequence (i.e. 0, 1, -1, 2, -2, 3, -3, etc.) is greater that the qth number or vice versa. This is a far worse outcome actually than not having a ‘starting point’ since ordering of numbers in a sequence should be a given rather than something that is determined after the fact. This is why, while listing integers, the convention …, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, … is to be preferred than the one suggested at the start of this paragraph, even though that one is observably more compact.

Nevertheless, my point is that, as soon as we start extending the set of numbers, we are faced inevitably with a trade off. Yet, just because the gains outweigh the losses, it does not mean that we should forget that there was a loss. In the case of extending from the whole numbers to the integers, the loss is not massive and, hence, it is often ignored.

Splitting Headache

However, what happens when we consider division? Clearly dividing two integers does not necessarily yield an integer. But before we even get there, we have to consider the possibility that the divisor might be zero (e.g. 1÷0). What would that mean? And what would the result be? Since answering these two questions will take us too far afield for this post, I will leave it to the reader to read my post My Unbounded Mathematical Trauma to get an idea of why division by zero is prohibited.

But returning to division by a non-zero divisor, we can readily see that 1÷6 does not yield an integer. When students are introduced to these ‘numbers’, the term used is ‘fraction’. And the teacher may use slices of pizza to make her students understand what the fractions denote.

Technically, however, the teacher has introduced the students to rational numbers. But we do not tell the students this. For some reason we do not tell them that these ‘fractions’ are actually instances of rational numbers. We wait for a few years before introducing them to this technical term. Why? I mean, when we teach them that a fraction is a part of a whole, we also teach them that there are improper fractions and mixed fractions. So we expect students to be able to parse through different cases to determine what kind of fraction they are dealing with. Is it too much then to tell them that the fraction can also be considered to be a ratio of numbers? (Yes, that’s why they are called ‘ratio-nal’ numbers.)

Anyway, I digress. Coming to the rational numbers, we can see that we have managed to have a set of numbers that is closed for the operation of division as well. That is, the sum, difference, product, or quotient of any two rational numbers will always be a rational number, subject, of course, to the prior condition that we do not allow division by zero.

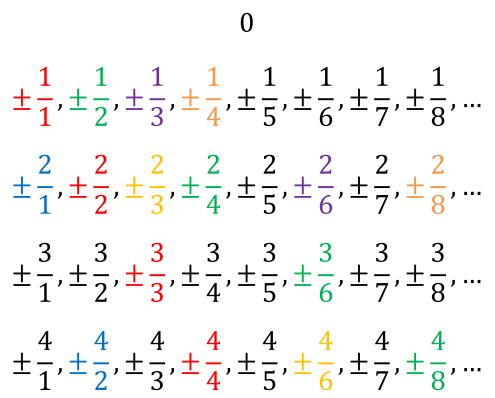

However, now we have lost even the ability to recite the numbers in a way that orders them. That is, I cannot recite numbers a, b, c, d, etc. with the assurance that I will always have a < b < c <d or even, as in the case of integers, |a|<|b|<|c|<|d|. To explain this last case, we can list the integers as 0, ±1, ±2, ±3, etc., thereby ensuring that there is a definite ordering of the integers, even though this is only in terms of the increasing ‘distance’ from 0 rather than ordering of the numbers themselves, as observed earlier. However, there is no such scheme of ordering the rational numbers that will ensure a strict order relation between successive numbers in the sequence. For example, consider the ‘ordering’ in the figure below:

The numbers with the same color have the same value. Note that, since there are infinitely many numbers in each row and infinitely many rows, there can be no way of reciting the numbers with the guarantee

- that all the numbers will be recited,

- that they will be recited in either increasing or decreasing order, and

- that there will be no repetition of numbers that have different rational form but the same value (i.e. equivalent fractions).

Hence, while we can certainly place any two rational numbers in an order relation, we have lost the ability to recite every rational number in order and without repetition. Since we do not use rational numbers for enumeration, this loss too is something that mathematicians have found acceptable.

Disempowering Empowerment

So far we have dealt with the four main mathematical operations – addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. And we have landed upon a set of numbers, namely the set of rational numbers, that is closed for all the four operations.

However, there is a fifth mathematical operation – exponentiation. What happens, for example if we perform the operation of exponentiation on rational numbers? We can see that expressions like (2÷3)2 or (1÷4)5 will yield a rational number as the result. However, this is not guaranteed. For example, 2½ is famously not a rational number, an elegant proof of which most students in India are introduced to in the 9th or 10th grades. However, since the expression 2½ shows up as the length of the hypotenuse of an isosceles right angled triangle with legs of unit length, the only conclusion we can reach is that 2½ represents an actual number.

Since numbers of this sort are not rational, they were called irrational, another poor choice by mathematicians. We still do not have closure, as we can see with the expression (-2)½. We will address this shortly.

But irrational numbers also suffer the same loss as rational numbers. However, there is a further loss when we consider that now we cannot even hope to list all the irrational numbers even using the earlier idea of infinitely many rows each containing infinitely many numbers. After all, we could consider 2½, 2⅓, 2¼, etc., 2⅔, 2⅖, 2²⁄₇, etc., leading us to the conclusion that every irrational number can potentially yield infinitely many irrational numbers!

However, the irrational numbers present a further conundrum. To illustrate this, let us remind ourselves of two things. First, the set of rational numbers is closed for the operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. Second, the sets of rational numbers and irrational numbers are mutually exclusive. That is, while it is true that integers, like 2 or 3 or -5 can also be considered to be rational numbers (i.e. ²⁄₁, ³⁄₁, and ⁵⁄₁ respectively), no number can be both rational and irrational at the same time. This stems from the definitions. Rational numbers are defined as numbers that can be expressed as p÷q, where p and q are integers and q≠0. Irrational numbers are defined then as numbers that cannot be expressed as p÷q, where p and q are integers and q≠0. Hence, the way these two sets of numbers are defined ensures that there is no overlap.

However, consider the numbers (√2)(√2) and √2. It is relatively easy to show that the first number is indeed irrational. The second number, of course, we have already encountered. However, now consider the number ((√2)(√2))(√2). A few deft simplifications will show that this number evaluates to 2.

In other words, we have reached a strange phenomenon, where the operation that necessitated the definition of irrational numbers, that is exponentiation, is the operation that makes the set of irrational numbers itself not closed to exponentiation. In particular, exponentiation is an operation that allows the possibility that two rational numbers would yield an irrational number and two irrational numbers would yield a rational number!

So now we have even lost the ability to determine beforehand the kind of number (rational or irrational) that would be the result of the operation. Things are getting quite murky. Yet, none of this is ever mentioned in formal high school education, though I know that many students would actually be fascinated by such ‘weird’ knowledge. Instead of allowing them to see the droll and whimsical side of mathematics, we inundate them with the sober and staid. God forbid that we should allow them to see the curious side of the subject that might fire up their imaginations!

The ‘Real’ Ideal

Since the sets of rational and irrational numbers are mutually exclusive (i.e. do not overlap), and since it seemed initially that these are all the numbers we would ever encounter, mathematicians named the set of both rational and irrational numbers the set of real numbers, another poor choice by mathematicians. The real numbers present us with the same difficulties as the rational and irrational numbers. There is no way to recite them all, no way to recite them in order, and no way to ensure we won’t repeat any number.

However, in addition, even the matter of determining an order relation between two numbers, while theoretically possible, is increasingly difficult. With the rational numbers it is relatively simple to determine which of a÷b and c÷d is larger. This is not the case with irrational numbers. This is because, irrational numbers also include numbers, like π and e, that are not the result of algebraic operations. These numbers, called transcendental numbers, are not numbers that anyone necessarily medicates on! 😜 However, they have indeed been the focus of mathematical contemplation. These numbers do not arise as solutions to any polynomial equation, which is why they are not considered to be algebraic irrational numbers. Rather, their origins are different and we cannot take a diversion to those origins in this post.

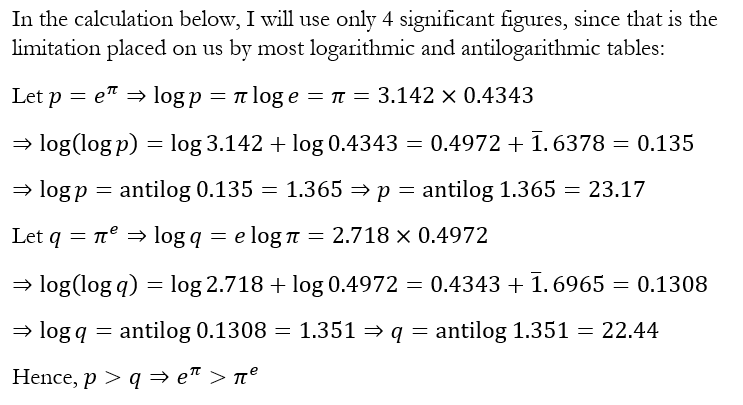

However, these transcendental numbers, precisely because they are not the result of any algebraic operations, do not lend themselves to easy comparison. A famous question, for example, asks which of eπ or πe is larger. Neither of these expressions is easy to evaluate. We could use logarithmic tables to reach the answer. This is shown below.

Alternately, one could use a brute force approach and, with a calculator, determine that eπ = 23.14069… and that πe = 22.45915…, making the first larger. Note here that the above values obtained by the tables differ from the calculator values because the tables are limited to 4 significant figures. If the two numbers we are comparing are actually closer to each other than eπ and πe are, the tables may not give us reliable results.

However, by taking either of these approaches, we did not use any mathematical insight. Hence, even though we know the answer to the question, we have gained no knowledge of the exponential function nor either of the two numbers involved in the question. This is the mathematical equivalent of a pyrrhic victory. We have defeated the ‘enemy’ but have actually gained nothing from the process. There is an elegant approach to solving this and gaining some key mathematical insights. However, since it uses calculus, I will save it for a later post.

Hence, while any two real numbers have a definite order relation, we have lost the ability to determine that order relation in all cases. Since we normally deal with numbers the ‘size’ of which we are somewhat aware of, this loss does not reveal itself too often. However, a little reflection would reveal that this is actually a huge loss. Think of it. Now, given two random real numbers, there is no sure fire way of determining which one is greater and which is lesser without the use of computers.

However, remember where we started? Numbers came into use because we wanted a way of quantifying things. “How many baobab fruits did you gather?” was a pertinent question. Now, however, we have actually lost the ability to determine between arbitrary real numbers which one represents the larger quantity. In other words, ironically, by the time we reach the largest set of numbers most people might ever work with, this set does not allow for us to use the numbers for their original purpose! But there is more.

Imaginary Complexification

Backtracking a bit, recall that the expression (-2)½ indicated that there is a bigger issue of closure surrounding exponentiation. This is because the square of a real number cannot be negative, thereby making us reach the conclusion that, whatever (-2)½ represented, it could not be a real number. Since they had already named the real numbers, mathematicians chose the easy way out and named the numbers that result from taking the square root of negative numbers imaginary numbers. After all, if what is not rational is irrational, then what is not real must be imaginary, right?

Anyway, despite the unfortunate nomenclature, these numbers were eventually accepted. However, in accepting these numbers we lost something else. Given two real numbers, we can, at least theoretically, determine an order relation between the two, even though, as we have seen, it may be impossible without the help of a computer. However, given two complex numbers, the very idea of an order relation does not exist. Now it is absurd to say something like a + bi < c + di or anything similar. This property is often mentioned in classes.

However, what we have reached is a kind of number that even theoretically denies the attempt to quantify it. In other words, with the inclusion of complex numbers, we have reached a situation where the very purpose for which numbers were conceived, namely quantification, is rendered meaningless! I do not know how many other mathematics teachers have realized this, nor, if they have, what they make of it. However, I know two things. First, I have never had a discussion with another mathematics teacher about the irony inherent in the inclusion of complex numbers that renders meaningless the very purpose for which we contrived the existence of numbers. Second, the complex numbers are as ‘real’ (i.e. not figments of our imagination) as the numbers classified as real. Hence, whatever property might belong to the complex numbers must be something that belongs to numbers in general since the complex numbers is the most general group of numbers that we have conceived.1

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

It is as though the whole field of mathematics has played a big joke on us and is having a good laugh at our expense. We began with the simple idea of wanting to enumerate, and therefore quantify, things. But as we moved on with our attempts to manipulate these mathematical entities that we call ‘numbers’, the numbers hit back at us. For now, if we want a set of ‘numbers’ that is closed for all the five operations, it comes at the expense of the very idea of enumeration and quantification.

This has enormous ramifications for our attempt to ‘control’ the world through the use of mathematics. We use mathematics in the sciences, in the humanities, and even in the social sciences. Indeed, even software that is used for illustration and animation cannot but use mathematics heavily. We have become a global culture that is so highly dependent on mathematics that, were it conceivable that tomorrow the rules of the operations would change, the edifice of our contemporary world will come crashing down on us even as the majority of us remain clueless about the mathematical underpinnings of this fall.

Yet, at the foundations of this endeavor we find these lifeless entities that we call ‘numbers’ fighting back. In our desire to not have any exceptions, for that is what the closure property entails, the ‘numbers’ have asserted themselves and given us a mathematical world in which the very assumptions of mathematical purpose have been undermined.

Oh, of course, we can just limit ourselves to the whole numbers as does Number Theory. But then we can only use addition and multiplication without restraint. We can choose to include the integers, thereby allowing us unrestricted use of subtractions. And so on. But as our desire to use mathematical operators without restraint increases, we keep losing something along the way. Initially, the losses are so minor that we barely think of them as losses.

However, the extension of the set of numbers extracts from us an inexorable and increasingly exorbitant price until finally we reach the situation where the very raison d’etre for numbers is rendered unintelligible. And so traumatized are we that we have paid such a high cost that we only mention it in passing, as though in a guarded whisper, without contemplation of what this turnaround might mean.

Win the Battle, Lose the War

So what does this turnaround mean? The impetus to conceive of new numbers comes from the non-closure property of the existing set of numbers with respect to some mathematical operation. In other words, this is something that is inescapable. As soon as the two gatherers had returned, one with arms full of baobab fruits and the other empty handed, they would have needed some way to express the fact that the second owed the first a certain amount of baobab fruits. As soon as a group returned successfully from a hunt and would have started to divide the animal, they would have needed some way to determine how to share the animal fairly.

In other words, at least till we get to rational numbers, which, remember, is closed for all the operations except exponentiation, the ideas of these numbers arise spontaneously from our lives as communal creatures. Please note that I am not saying that hunter gatherers had any mathematical systems, let alone anything similar to what we learn even in grade school today. All I am saying is that the ideas that eventually get formalized into the various kinds of numbers up to and including rational numbers arise from our communal life.

However, the first encounter we would have had with irrational numbers would likely have been, as discussed earlier, in the context of geometry. I mentioned the hypotenuse of an isosceles right angled triangle. But does this arise only in the context of a mathematics class? Hardly! Rather, as soon as we started measuring land, which would have been something we thought necessary only after settling into a sedentary life, we would have needed to measure hypotenuses. In other words, I hypothesize that it is our becoming sedentary that forced upon us new mathematics that required the irrational numbers and, eventually, the complex numbers.

This does not mean, however, that the irrational numbers and complex numbers are purely inventions of the human mind. Rather, for example, as the Schrödinger equation indicates, we cannot describe natural phenomena without the imaginary numbers.

In other words, the operation of the natural world seems to require this largest set of numbers that we have encountered. Yet, it is precisely this set of numbers, closed for all 5 mathematical operations, that undermines the very reason for which we humans contrived language for speaking of numbers.

Mathematics has, for most of its history, attempted to construct a solid edifice that is impervious to any attack. However, as Kurt Gödel demonstrated with his twin incompleteness theorems, such an endeavor is an exercise in futility. And we have seen in this post that even the very idea of closure – something I have labelled an attempt to ‘control’ the numbers – presents us with ultimate defeat. Perhaps it is the mathematical equivalent to what Princess Leia said when she told Grand Moff Tarkin, “The more you tighten your grip the more star systems will slip through your fingers.”

- Quaternions and octonions are not actually any new kind of number. Rather, they are ways of representing vectors in number form by extending the ideas obtained from complex numbers. ↩︎

Leave a reply to From Fractions and Pizzas to Encryption – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply