Fractions and the Loss of Information

In my previous post, I had looked at what is gained and more importantly what is lost as we expand the set of numbers we work with. The discussion in that post centered around the closure property of sets of numbers with respect to various mathematical operations. We saw that the set of rational numbers is closed for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

Rational numbers, of course, are introduced to us with another name – fractions. And while our teachers may not spend much time on the notion, we are aware that fractions involve a specific order for the operations. For instance, we know that 3/4 is quite different from 4/3. This is a result of the non-commutative property of division. But what it tells us is that order is important.

Fractions, of course, are one of the bread and butter concepts in mathematics, taught to students from probably as early as Grade 1. However, for the most part, students are taught how to perform mathematical operations using fractions.

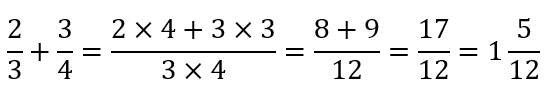

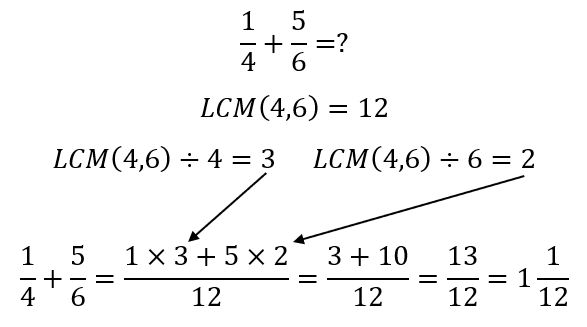

So, for example, students soon learn how to add fractions with the same denominator, later progressing to fractions with different denominators. Here we may see the students being taught to do something like:

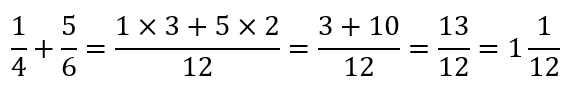

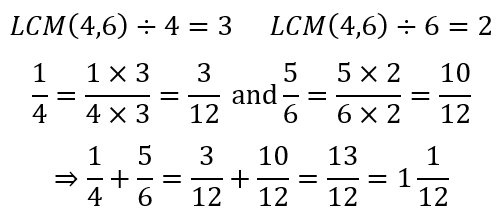

They will later move to calculations where the LCM of the denominators is not the product of the denominators. For example:

A few teachers may give the students some additional insights like the following:

Here, the teacher has probably explained how the LCM plays a role in determining with what number each numerator needs to be multiplied. There is some rationale involved, which hopefully would help the student in future calculations.

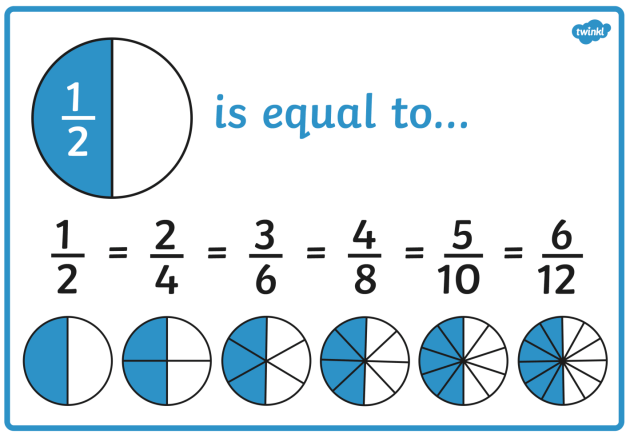

However, in all of this, the meaning behind the manipulations is lacking. Discerning teachers, of course, know that what we are doing here is using the ideas of equivalent fractions. For instance, once we have determined that the LCM is 12, the teacher may explain as follows:

Here, the concept of equivalent fractions helps the student see how the two fractions, which originally had different denominators, can be added together if the denominators are made equal. The idea of equivalent fractions, of course, is powerful as can be seen from the simple matter of addition of fractions. All we need to do is make the denominators equal through the use of the LCM and we are good to go! Some teachers may use images like the one at the start of this post to demonstrate to students the truth of equivalent fractions, which is essential for students to be willing to trust and, therefore, learn the process.

In all of this, the order of operations is crucial. We cannot choose an arbitrary order and still ensure that what we have done remains meaningful. Some students are perhaps more trusting of the process and learn it more quickly. Others perhaps remain unconvinced and do not adopt the wisdom taught to them.

Loss of Information

Returning to the idea of equivalent fractions, while it is true that 1/2 and 3/6 have the same numerical value, they each contain different information. And if we do not communicate to the students that information is being changed, they will only learn to perform the operations in a mechanistic way. And no one, believe me, no one enjoys tedious tasks that are inherently mechanistic.

So how do we communicate the change of information? Why are 1/2 and 3/6, while numerically equal, informationally different? And what does this have to do with the idea of order? We will address the question about order later in this post. For now, let us address the issue of information.

1/2 of course means 1 part of the whole, where the whole has been divided into 2 equal parts. Similarly, 3/6 means 3 parts of the whole, where the whole is divided into 6 equal parts. The number of parts selected is in the numerator, while the number of parts into which the whole is divided is in the denominator. And we make both denominators equal because then the ‘size’ of all the parts becomes equal, allowing us to add (or subtract) without hindrance.

Teachers know this. And discerning teachers tell their students about this. Indeed, we should tell them this for two reasons. First, mathematics becomes increasingly abstract as we learn more and more. Developing in students the skill of thinking mathematically is easier when the mathematics involved can still be rooted in actual physical reality. Students who develop this skill early can then hone the skill for contexts that are more abstract. In fact, this skill cannot be developed in High School because by then the students would have developed the prejudicial skill of rote procedure, which deceives them with a false idea of mathematical clarity when in fact all they are doing is executing an algorithm.

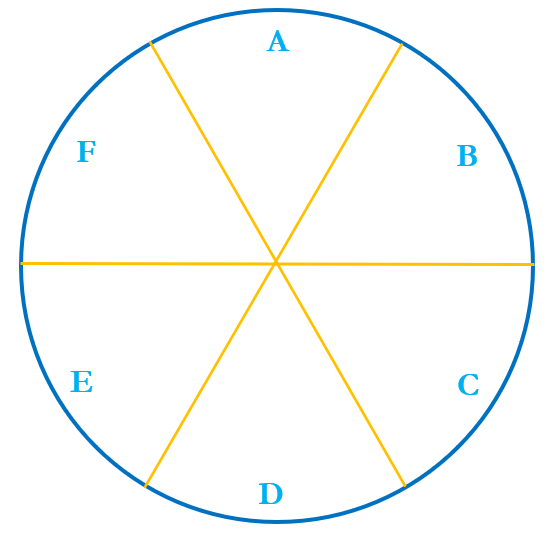

Second, if the situation is complexified even slightly, it does matter which 3 of the 6 parts a person gets. In higher classes the difference between an arrangement and a selection is crucial. However, students who have not been exposed to a slight complexification of the situation are rarely able to comprehend the difference between an arrangement and a selection. In order to introduce yourself to a slight complexification of the situation with a view to convincing yourselves that it does matter which parts a person gets, consider the pepperoni pizza below, which I will use to elucidate the point.

Tossed Pizza

This pizza gives us a situation of a slight complexification of the issue of who gets which parts. In the figure above, the individual sectors A-F are congruent to each other and it would seem that there is nothing to distinguish between one piece and the other five. However, I said that this was a pepperoni pizza. But where’s the pepperoni?

As it so happens, the person who was tasked with putting the pepperoni slices on the pizza has a twisted mind and does not want to make things easy for the customer. (Maybe in a previous life I worked at a pizza place?) According to the recipe, the pizza needs to be topped with 15 slices of pepperoni. So this is what she does:

Now if two friends (X and Y) share this pizza, each of them would get half the pizza. But which half? You see, now there are 20 ways in which the friends can divide the pizza. X could get: ABC, ABD, ABE, ABF, ACD, ACE, ACF, ADE, ADF, AEF, BCD, BCE, BCF, BDE, BDF, BEF, CDE, CDF, CEF, or DEF, with Y getting the other three slices. However, now, even though X gets ‘half’ the pizza, he may get as few as 3 slices of pepperoni (ACE) or as many as 12 (BDF).

Gamification and Information

Teachers regularly use pizzas as teaching aids for teaching concepts related to fractions. However, we depend on an idealized pizza in which something like in the figure above does not happen. But idealized pizzas do not exist. They are never perfectly circular! The slices are rarely even close to a sixth (or quarter or eighth) of the pizza! Yet, when we use the non-ideal pizza as a teaching aid, we are actually helping the students to develop their power of abstraction and the skill of using their imagination. Now, despite the obvious fact that the slice that one student chose is bigger than the one another student chose, we encourage them to entertain the fiction that each of them actually received a sixth of the pizza. We should encourage this kind of abstraction and imagination in students.

In addition, however, Fig. 3 above allows for some other aspects of complexity. For example, I could ask the students, “If I am not too hungry, but really like pepperoni, how little of the pizza could I eat while still ensuring I eat at least half the pepperoni?” Now we have an overlay of two problems related to fractions. Of course, the answer presents itself quite quickly. I could eat as little as a third of the pizza (DF) and still eat 8/15 of the pepperoni. Since I chose an extreme case, represented by the condition ‘at least half’, there is only one solution.

However, if I relax this to something else, say, “More than a third,” the number of solutions balloons. In good mathematics textbook form I say, “The solution to this is left to the reader.” 😉 Moreover, since this is an even numbered problem, the answers are not provided! Just kidding. You should be able to identify 6 solutions.

Now if we add a third friend, Z, we can find a solution that is equitable in terms of fraction of the pizza and fraction of the pepperoni if we divide the pizza into groups AD, BE, and CF. Now each friend truly gets a third of the pizza – 2 slices of pizza and 5 slices of pepperoni!

We could make this a little more interesting. We add a rule to a two player game: No one can choose a slice adjacent to the slice chosen by the previous player. In other words, if the friends are X and Y, then, if X chooses slice B, then Y cannot choose slices A or C. The goal is to obtain at least 7 slices of the pepperoni. Is there a winning strategy? By the way, there is. The reader is encouraged to comment with the proposed winning strategy. This game can be made even more interesting by having the number of pepperoni slices on a pizza slice be randomized without repetition. There are 120 different arrangements possible. Now is there a generalized winning strategy? By the way, there isn’t. But is there a way to prove that there isn’t or do we have to try all 120 arrangements and then conclude that there is no pattern? In a later post I will explore the issue of determining beforehand if a proof of some proposition exists or not. Discussing it here will make this post too long and will take us far off course.

What we can see, however, is that if all we are concerned about is the ‘size’ of the fraction, represented in the practice of finding equivalent fractions, then we lose information along the way. Loss of information is a crucial aspect of mathematics that we, unfortunately, do not focus on. There are, of course, other areas of information loss that I did not cover in the previous post and cannot cover here.

What we have seen in the example of the pizza is that this simple model can be used to teach about fractions and especially equivalent fractions. And as long as each slice was identical, that was all we could get from our pizza. However, once we added the pepperoni slices we introduced the possibility of ordering or arranging the slices. Now it did matter who got which slice. Indeed, when we consider gamifying the situation, the loss of information becomes something that must be avoided because the different situations of the game depend on the granularity of the descriptions.

However, to understand how a game can proceed, it is crucial that we are able to describe the possible ‘moves’ that a player can make from a given situation. This means being able to fully describe all possible routes the game could take. Actually, it requires being able to determine the number of routes that the game could take, for it is with the numbers that we can obtain the related probabilities of a win or a loss.

Earlier, when considering the pepperoni pizza with 6 pizza slices and 15 pepperoni slices, I said that there were 20 ways in which the friends could divide the pizza. While it was relatively easy to list all the 20 ways, nothing really is gained by this kind of brute force approach to the problem. For example, we could ask questions like, “Would it always be 20 no matter how many slices of pizza were there?” or “If the number of pizza slices play a role, what kind of role do they play?” or “What is the role, if any, of the pepperoni slices in determining the answer?” These are questions that must be answered if we are to be able to design a game that is worthwhile.

Deep Dive Pizza

In other words, we are asking for some general insight about the selection of the pizza slices, with or without taking the pepperoni slices into account. The fact that we listed the 20 possible ways two people can evenly share a 6 slice pizza tells us absolutely nothing other than that we are capable of making an exhaustive list through the exhausting brute force method! Let us try to gain some insight through a couple of processes.

So let us consider how the division of the slices might take place. We could either have X select 3 slices, leaving the remaining slices for Y. Or they could alternate turns while taking 1 slice at each turn. Both processes should yield the same result. Let us consider the first approach.

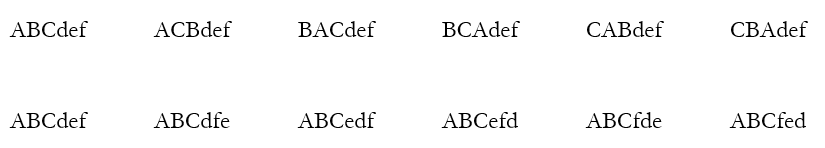

In effect, for each slice, there are only two options. It either is selected by X or is not selected by X and hence goes to Y. Hence, for each slice we have 2 possible outcomes. Below I list the possible outcomes with the convention that upper case letters indicate the slice goes to X while lower case letters indicate the slice goes to Y. I have lifted the restriction that X and Y each get 3 slices.

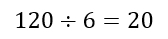

In the above, the distributions in red indicate the ones in which both X and Y get 3 slices each. We can see that there are 64 different ways of distributing the 6 slices. This is the same as 26, that is 2×2×2×2×2×2, which is what we would expect since there are 2 outcomes for each slice. The number of red distributions is 20, as expected. But if we pay close attention, we can see that, since the order ABCDEF does not change, all we are doing is selecting which 3 of the 6 letters must be capitalized, indicating that the corresponding slice goes to X.

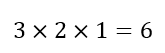

How would we go about selecting the 3 letters for X? To begin with, there are 6 options to choose from. Once that is done, for the second letter, there are 5 remaining options to choose from. For the third letter, there are 4 remaining options to choose from. Hence, the number of ways of picking 3 slices out of 6 will be:

Adjusting for Overcounting

However, see the image below:

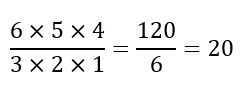

All the elements listed represent X getting slices A, B, and C, with Y getting slices D, E, and F. However, in the first row, we can see that there are 6 ways in which X can pick the 3 slices. Similarly, in the second row, we can see that there are 6 ways in which Y can pick 3 slices. Hence, the 120 we obtained represents an overcounting by a factor of 6. This allows us to conclude that the number of ways of choosing 3 slices out of 6 is:

But where did we get the 6 from? As seen in the first row of Fig. 5 above the letters A, B, and C can be arranged in 6 ways. We can use the same method as we did earlier. There are 3 options for the first position, 2 for the second, and 1 for the third, yielding:

Hence, as of now, we can conclude that what we have done is:

Recall that the 6 in the numerator above represents the number of slices the pizza is cut into. Also, the 3 in the denominator and the number of numbers in the numerator and denominator represents the number of slices X has to choose. We have now gained some insight about the problem and can extend it beyond our 6 sliced pizza.

Extension 1 – Increasing the Set Size

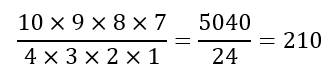

Suppose, for instance, that my friends have recommended 10 books to me to read. However, I only have time to read 4 books. How many selections of books can I make? Given the reasoning above, we would conclude that the number of selections is:

Right away we can see that, while the numbers 10 and 4 are reasonably small, the result (210) is quite prohibitive. Not only would it be extremely tedious to list all the possible selections, it would be even more wearisome to check for possible repetitions and omissions.

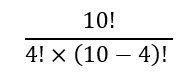

The above expression can be written in a more compact form if we recognize that, since the numerator starts with 10 and contains 4 numbers, there are 6 numbers from 1 to 10, namely, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1, that are missing. Hence, we can multiply the numerator and denominator by the product of these six numbers to get:

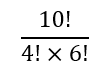

Here there are three groups of numbers that I have designated with different colors. All of these groups have the property that they constitute the product of all the natural numbers from a particular number (10, 4, or 6) down to 1. Mathematicians have decided to call such a product a factorial and designate n factorial with n!. Hence, the above can be written as:

And since the 6 was obtained as the difference between 10 and 4, we can write this as:

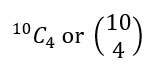

Given their penchant for brevity, mathematicians have shortened this to:

Of course, as we saw earlier, we must have 10C4 = 210. Hence, there are 210 ways of choosing to read 4 out of 10 books.

Extension 2 – Increasing the Number of Partitions

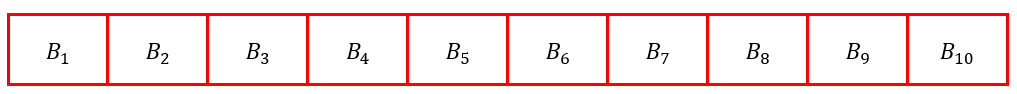

But suppose I wanted to be more granular about my decisions concerning the books. Say I want to divide them into three categories – read now, read later, not read. Given 10 books, how many ways are there to partition them into these 3 categories? We can begin by placing the books in a row as depicted below:

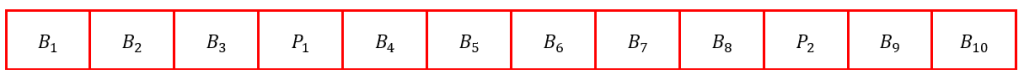

Here, the subscripts are only given to differentiate the books from each other. In order to divide them into the three categories, we can consider placing two partitions, as shown below:

From the above, we can conclude that B1, B2, and B3 are in the ‘read now’ category, B4 to B8 in the ‘read later’ category, and B9 and B10 are in the ‘not read’ category. What we can see are three things. First, the number of partitions (2) is one less than the number of categories. This will always be the case. For example, to divide the group into 5 categories, we will need 4 partitions. Second, because of the introduction of the partitions, the total number of items we are dealing with has increased by the number of partitions. Third, the problem has been simplified to choosing the positions for the partitions among all the items. In the above case of separating the 10 books into 3 categories, we have to choose where to place the 2 partitions among the 12 possible positions. But we already know how to do this. This can be done in 12C2 = 66 ways.

Extension 3 – Including Order Preference

So far we have considered all the books to be identical. In fact, I said that the subscripts were unimportant. However, we who read books know that the actual books are important. The books I will actually read are important to me. From the list of top 15 paperback nonfiction New York Times best sellers, I urgently read Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman and The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk. And I am interested in reading Think Again by Adam Grant, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine by Rashid Khalidi, and The Glass Castle by Jeanette Walls. The other 10 books, while probably excellent, do not grab my interest and I will never read them. How do we include such preferences in our calculations?

First, I could arrange them in a preferred order and place a partition where I differentiate between ‘read now’ and ‘read later’ and another between ‘read later’ and ‘not read’ as shown below.

The arranging of the 10 books can be done in 10! = 3,628,800 ways. Once we have done that, the two partitions can be placed in 66 ways, leading to a total of 66×3,628,800 = 239,500,800 ways! Just with 10 books! Actually, if we had 12 books and separated them into the same three categories, it could be done in 14C2×12! = 43,589,145,600 ways! In other words, with just 12 books we would need more than 5 planets with population similar to ours before we would be forced to repeat a reading plan!

The Sky’s the Limit

We can generalize the above discussion as follows. If we have n items that have to be put into r categories, with the order being irrelevant, then it can be done in n+r-1Cr-1 ways. Of course, we could include the idea of preference or ordering into the picture. Since there are n items, they can be arranged in n! ways. Hence, the number of ways of partitioning these n items into r different groups if the order is important is n!×n+r-1Cr-1.

We could visualize this in a different way. Consider a pathway that is filled with forks. In a game, this could represent different choices that the player makes at each juncture of the game. In an election, this could represent the casting of votes by each voter. For a lock – physical or virtual – this could represent differing positions for the pins.

Normally, with binary data, a 128 bit SSL encryption would involve 2128 = 3.40×1038 possibilities. The strategy I am thinking of here would also involve a 128 bit encryption. However, here the 128 bits are divided into 20 ‘characters’ each chosen from a 64 character set. Hence, each ‘character’ will use 6 bits. This leaves 8 bits unused. However, 4 of these 8 bits will specify how many categories the ‘characters’ can be divided into. The last 4 bits will specify which of the possible categories specified by the preceding 4 bits is actually in play. This means that the ‘characters’ could be in from 1 to 16 categories. Choosing and arranging the 20 characters can be done in 20!×64C20 = 4.77×1034 ways. Using the expression n+r-1Cr-1, we can calculate that the partitions can be placed in 5,567,902,560 ways. This yields a total number of possibilities as 2.67×1044, 6 orders of magnitude better than the current 128 bit SSL. The current 256 bit SSL encryption gives a whopping 1.16×1077 outcomes. With my proposal we get 1.33×1083 outcomes, again 6 orders of magnitude more.

I grant that this idea is still in a very embryonic stage. However, the 6 orders of magnitude is a significant improvement. For example, assuming a brute force algorithm can attempt 1 quadrillion (1015) attempts per second, the 128 bit SSL will be able to last for about 4×1018 years and the 256 bit SSL about 3.7×1054 years. The corresponding figures for the proposal I have made are 8×1021 years and 4.2×1060 years, both clearly significant improvements. However, coding this dynamic encryption rather than the current quite static SSL encryption will be considerably more involved and requires much more coding expertise than I have! So I leave the task to those better skilled in coding than I am while I consider other aspects of mathematics that interest me.

Leave a reply to Learning to Count – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply