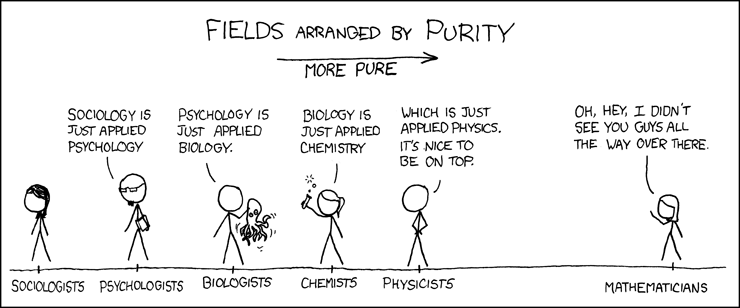

Grasping for the Absurd

Anyone who has studied mathematics till at least the middle school will know that there are certain mathematical ‘artifacts’ called ‘proofs’. Whether we understand them or not, proofs form one of the foundational structures of mathematics, allowing us to take one idea and extend it logically in a variety of directions to obtain new, and often surprising, results. Since proofs are often just thrown at us without much of an explanation of how the argument is mathematically rigorous, I wish to devote a few posts (not consecutive) to dealing with specific approaches to proofs.

If we had a good mathematics teacher in middle and high school, she/he would have at least told us about a few different approaches to proofs. Very likely, this would have come in the context of geometry, though it is possible that some teachers experimented with introducing their students to proofs in arithmetic, such as that there are an infinite number of primes or that every number has a unique prime factorization. While these may not have been done in a very formal manner, given that the students might have lacked the symbolic language for executing a formal proof, I applaud such teachers.

In this post, I wish to address a common approach to mathematical proof known as ‘proof by contradiction’ or more technically reductio ad absurdum, Latin for ‘reducing to the absurd’. I don’t know about you, but to me there’s something more visceral in the statement ‘reducing to the absurd’ than ‘proof by contradiction’. I think it’s time we recovered some of these older, more visceral statements and junked the more cerebral statements. I mean, mathematics is cerebral enough on its own! We don’t need more phrases that are cerebral. We need something that gets us in the guts! So let’s see what absurdities we can avoid.

A Note on Proof

Before we move to that, I wish to say a word about the word ‘proof’. It has a very distinct meaning in mathematical contexts. Unfortunately, the use of the word in everyday speech does two things that render our civil discourse difficult. First, most of us know that ‘proof’ is something that belongs to the rigorous realm of mathematics. Hence, when anyone uses the word ‘proof’, we assume they are speaking of the same kind of thing as mathematicians speak of when they use the word ‘proof’. In other words, we are not discriminating enough to recognize that words are equivocal and have differing meanings in different contexts. Second, we assume that rigorous ‘proof’ is possible in fields outside of mathematics. Since the word ‘proof’ is used, in my view illegitimately, in other fields, and since we have not allowed for the equivocality of words, we conclude that rigorous ‘proof’ is possible in other areas.

Hence, I have often heard claims such as that the theory of evolution has been proved or that the theory of relativity has been proved. Similarly, the legal idea of ‘proof beyond reasonable doubt’ is also not an instance of ‘proof’ per se. All these are examples of abduction, which I dealt with in an earlier post. They are inferences to the best explanation based on the available data. Abduction is a powerful tool that should not be discounted. However, since it is based on limited data, it cannot function as mathematical proof. Rather, mathematicians use the term ‘abduction’ or more commonly ‘inference’ to denote this kind of reasoning.

The conflation of the mathematical term ‘proof’ with other methods of reasoning not only undermines what the explorations in other fields actually entail, but also it assumes that these theories rest on as firm foundations as mathematical theorems. This results in a failure to understand what is being claimed in other fields when a theory is proposed, thereby actually proving to be a hindrance to inquiry in the other fields. The most notable difference is that mathematical theorems are not subject to change based on any further evidence. This is patently untrue about the theories in the sciences and other non-mathematical fields, which, being data driven, are subject to revision when new data becomes available.

Mathematical proof, however, leads to a statement – possibly a theorem – that is true for all instances of the item being studied and is not subject to change. If it could change, it is not something that has been proved. For example, the theorem that, in Euclidean geometry, the sum of the internal angles of a triangle add up to 180° is not something that is tentatively held. The claim of this statement is that there is no triangle in Euclidean geometry that does not satisfy this property.

With that out of the way, we can turn our attention to the method of reductio ad absurdum. The process of this method of proof is ingenious and I would like to thank the first person who thought of it. It involves making an assumption and following that assumption logically until we reach a point where the assumption is disproved. This means that, by assuming something is true, we are able to prove that its negation is also true. Since this is absurd, the conclusion is that the assumption must be false. Hence, the bottom line for this method of proof is the understanding that a claim and its opposite cannot both be true at the same time. When we assume that statement A is true and conclude that this must mean that its negation, ¬A, is also true, we have reached something that is ‘absurd’, hence the name.

I will consider two examples of reductio ad absurdum, which will enable us to see the brilliance and elegance of this line of reasoning. After that, we will take a step back to identify some important aspects of this method of proof. Following that, I will look at an interesting third example of reductio ad absurdum before drawing this post to a close.

Rationally Irrational

As mentioned in an earlier post, if we have an isosceles right angled triangle with legs of length 1 unit, Pythagoras’ theorem yields the length of the hypotenuse as √2 units, which I claimed is an irrational number. But how do we prove it?

We start by assuming the opposite to be true, namely that √2 is a rational number. Hence, we must be able to find two integers p and q such that p÷q = √2. Using the idea of equivalent fractions, which I dealt with in an earlier post, we make the additional assumption that p and q do not have any common prime divisors. Hence, p = 18 and q = 8 would not be allowed since 2 is a common divisor. Rather, for the same numerical value we can choose p = 9 and q = 4.

So we proceed to square the equation to get:

Now since p and q are integers, their squares must also be integers, from the closure property of integers over multiplication. Hence, the right side of the last equation must be even since q2, which is an integer, is multiplied by 2. This leads us to conclude that the left side must be even as well, since an odd number cannot be equal to an even number. Now, since the left side is a perfect square, it can be even only if p is even, since the square of an odd number is necessarily odd.

So we assume that p = 2k, where k is an integer. This will ensure that p2 will be even. This leads to:

Now, the left side of the equation is necessarily even, since k2 is multiplied by 2. This must mean that the right side of the equation is also even, which can happen only if q is even.

So what we have concluded is that both p and q are even. This means that they both have 2 as a divisor, which is absurd since we assumed they had no common prime divisors.

Suppose, though, that we tried this method on a number that is not irrational. So suppose we tried this with √4, which we know is equal to 2 and, hence, rational. If we proceed as before, we get:

Once again, since the right is a multiple of 4, it must be a multiple of 2 and, hence, even. This means the left side is even as well Proceeding as we did earlier, we get:

Here we do not have an absurdity because all we can conclude is that k = q, which does not violate anything we initially assumed.

What we can conclude is that this process is foolproof. If the number we are dealing with is irrational, it will yield an absurdity. But if the number is rational, we will not reach an absurdity. In fact, we can use this method to test for any number of the form:

where both m and n are positive integers. The reader is encouraged to proceed with the proof. I will post one in the comments in a week or two.

Infinitely Primed

This brings us to the second instance of reductio ad absurdum. Here I present Euclid’s proof that there are infinitely many primes. Note that I did not say, “The number of primes is infinity” because, as mentioned in an earlier post, infinity is not a number!

As with the case of the square root of two, we begin by asserting the opposite. In this case, we assume that the number of primes is finite. Let us say that there are n primes designated as p1, p2, p3, …, pn.

Now consider the number

Now, all natural numbers greater than 1, fall into two categories. They are either prime or composite. N is obviously greater than 1 and, hence, must be either prime or composite. If it is prime, then we have found another prime apart from those among p1, p2, p3, …, pn, which is absurd since we assumed that we had listed all the primes when we considered the n primes in this list.

So, perhaps N is composite. However, consider the product

It is clear that all the primes in our original list (i.e., p1, p2, p3, …, pn) are divisors of this product. Since the smallest prime is 2, it follows that none of the n primes are divisors of N. However, if N is composite, it must have a divisor between 1 and itself. And this divisor itself must have one or more prime divisors that are not in our original list. Hence, even if N is composite, we have proved the existence of at least one prime not in our original list, which is absurd since we assumed we had listed all the primes. For example, suppose our full list of primes is 2, 3, 5, 7, 11 and 13. Then N = 30031. But 30031 = 59 × 509, both of which are primes not in the original list.

In both cases, that is, if N is prime or if N is composite, we have reached an absurdity, which means that our original assumption, namely that there are a finite number of primes is false.

Down to Brasstacks

Let us now step back to see what features of both proofs allow us to pull off the reductio ad absurdum. In the case with √2, we had two options. Either this number was rational or it was irrational. In the case of the primes, N was either prime or composite. We can see that, in both cases, the possibilities describe what mathematicians call mutually exclusive and exhaustive sets. What in the world does this mean?

Mutually exclusive means that there is no overlap between the sets. That is, we cannot find a single element that belongs to both sets. In the case of rational and irrational numbers, this is achieved by the definition of the rational numbers, leading to the conclusion that any number that does not satisfy the definition must be irrational. Hence, through the definitions themselves we ensure that no number can be both rational and irrational. In the case of the prime and composite numbers, once again, mutual exclusivity is achieved through the definition of a prime number. Here it pays to note that the number 1 is considered to be neither prime nor composite. And since N is greater than 1, we know then that 1 is excluded from consideration. Among all the remaining natural numbers, each number either satisfies the definition of being a prime number or it doesn’t, thereby making it a composite number. Hence, once again, through the definitions themselves we ensure that no number can be both prime and composite.

I also mentioned that the sets are exhaustive. This means that there is no number under consideration that does not belong to one of the sets that have been defined. Once again, this is achieved by the definitions themselves. In the case of the rational and irrational numbers, one set is defined as satisfying the definition, leading to the other set automatically including the numbers that do not satisfy the definition. In other words, there can be no real number that does not fall into either category. Similarly, in the case of the primes and composites, the definition of one provides the definition of the other through the negation of the first definition. This means that, barring the exception of 1, there is no natural number that is neither prime nor composite.

So what we achieve by the categorization into rational and irrational or prime and composite is that every number under consideration, real numbers in the first case and natural numbers greater than 1 in the second, belongs to one and only one of these categories. In other words, for any number under consideration, there is no ambiguity about the set to which it belongs and there can be no other heretofore undefined set to which it belongs.

Actual v/s Potential Infinities

The idea of defining mutually exclusive and exhaustive sets is so groundbreaking that it is used beyond reductio ad absurdum and I will deal with these uses in a later post. However, here I wish to address one more example of reductio ad absurdum. Mathematicians differentiate between what they call ‘actual infinities’ and ‘potential infinities’. An ‘actual infinity’ refers to a complete set that actually lists infinitely many elements. A ‘potential infinity’, however, refers to a way of building the set so that all the infinitely many elements are potentially listed.

If the set of natural numbers is an actual infinity, then consider the following mapping from the set of natural numbers to itself.

We can readily recognize that this maps each natural number to its square. Quite obviously, the top row can be incremented by 1 indefinitely, yielding infinitely many numbers in the top row. Since the set of natural numbers is closed over multiplication, this means that each element in the top row has a corresponding square in the bottom row.

However, it is clear that the bottom row does not have quite a few numbers that actually belong to the set of natural numbers. For example 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, … are natural numbers that are not in the bottom row.

Now suppose the set of natural numbers represents an ‘actual infinity’. This would mean that it is possible to list all the natural numbers. Now consider the fact that every number in the top row has a corresponding number in the bottom row. Hence, the two sets represented by the two rows must have the same size. However, consider the fact that the numbers 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, … do not appear in the bottom row. Hence, the bottom row is missing some numbers in the top row. This means that the size of the set in the bottom row is smaller than the set in the top row.

So we have proved that the two sets have the same size and that they have different sizes, which is absurd. Hence, our assumption that the set of natural numbers is an ‘actual infinity’ must be a false assumption and should be rejected.

Applicability of Reductio ad Absurdum

We can see that reductio ad absurdum can be used in a variety of contexts. It is one of the more powerful methods of proof that mathematicians use precisely because the logic behind it is simple and elegant, namely that, if an assumption leads to an absurdity, then the assumption must be false. Also, from the three examples I have considered, we can see that it can be used in highly symbolic contexts (e.g. irrationality of √2) to contexts in which symbols are not even needed (e.g. ‘actual or potential infinity’ of natural numbers). Because of this reductio ad absurdum can also be used in non-mathematical contexts, as long as the logic is followed rigorously.

Suppose, for example, someone, trying to undermine some view that I hold, says, “All opinions are equally valid.” In response to this I could propose the opinion, “The opinion that ‘all opinions are equally valid’ is invalid.” Since this is an opinion and the original claim was that all opinions are equally valid, it must be true that the second opinion must be equally valid, rendering the first invalid!

The preceding paragraph actually highlights some serious flaws in argumentation that one encounters today. Many people make all sorts of claims that, if put in the context of reductio ad absurdum, would quickly fall to pieces. This stems from beliefs about climate change, politics, psychology, and religion, to say nothing about gender and sexuality, where, of late, some quite laughable assertions have been made that do not withstand logical scrutiny. I plan to explore one such claim in the next post. Till then, allow the absurdities to come to the rescue!

Leave a reply to Rationally Irrational – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply