Recap

In the previous post, I started a series of three posts focused on the number denoted by e. We then saw why it is the base of the natural logarithm and the base of the exponential function. We also saw the relation between e and compound interest. In this post we will try to determine the lower and upper bounds for e.

In order to do this, we need to do seven things. First, we will then ‘discretize’ the function

for integers n. Second, we will need to introduce ourselves to the limiting process. Here, we will only restrict ourselves to the cases where x becomes infinitely large. Third, we will introduce ourselves to the binomial expansion and obtain the lower bound for e. Fourth, we will show that the function

is an increasing function. This means that the value of f(n) increases as the value of n increases. Fifth, we will combine the limiting process and the binomial expansion to obtain a very common infinite series for f(x). Sixth, we will introduce ourselves to the idea of an infinite geometric series. Seventh, we will use what we know from the infinite geometric series and the infinite series for f(x) to obtain the upper bound for e.

Discretization

In order to proceed with what I have called ‘discretization’, consider the function

It is possible to prove that this function is defined for all positive values of x. We may not be able to calculate the value by hand. And we may not have a clue what

might even mean, let alone how to calculate it. Nevertheless, if f(x) is defined for all positive values of x it must be defined for all positive integer values of x. In this f(x) is transformed to f(n), where

This is something that we can comprehend because exponentiation to a positive integer, in this case n, only signifies repeated multiplication. So now, we have to only deal with f(n).

But now we have to show that f(n) is an increasing function. In more formal mathematical terminology, we have to show that f(n) is monotonically increasing. It is easy to see from the tables in the previous post that this is true. Below is one of the tables from that post.

Since the values of x chosen were all integers, the same table would apply for n, f(n), and Δf(n). We can see that, as n increases, f(n) also increases. But this is not how we prove things in mathematics! So is there another way to prove that f(n) is increasing? Yes there is!

The Limiting Process

But before we get to that, let us introduce some aspects of the limiting process. Consider the function

We can easily see that, as n gets larger and larger, the value of g(n) gets closer and closer to 0. This is seen in the table below.

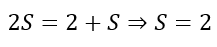

What we can say is that, as n gets infinitely large, g(n) gets infinitesimally closer to 0. Or to be rigorous, we say that the limit of g(n) as n tends to infinity is 0. Please note what this language is claiming and what it isn’t. First, it is not claiming that infinity is a number. God forbid! I have dedicated a whole post to ridding ourselves of that mathematical heresy. Second, it is not claiming that the value of g(n) ever becomes zero. It is impossible for the reciprocal of any number to equal zero. If this were not true, we could argue as follows.

But, as we know, division by zero is meaningless or ‘absurd’. Since this assumption leads to an absurdity, by the reasoning of reductio ad absurdum, we can conclude that the original assumption, namely that the reciprocal of some number can be equal to zero, is incorrect.

The way we denote the limiting process is by writing

The left side of the equation tells us what the variable of the limit is, in this case n, and how it is being made to vary, in this case getting infinitely large. It also tells us what function of the variable we are dealing with, in this case 1/n. The right side of the equation tells us the number that the value of this function approaches, in this case 0, as the variable (n) varies as specified.

Due to the limiting process, we can draw the following conclusions.

The table below can confirm our conclusions.

So what we have managed to prove, albeit not with great rigor, is that the ratio of an integer to its predecessor or to its successor approaches 1 as the integer gets larger and larger.

The Binomial Expansion and the Lower Bound for e

Now it is time for us to introduce another important result that we will be using. This is known as the binomial expansion. As seen in an earlier post, the number of ways of selecting r items out of n items is

Now consider the expression

This is called a binomial expression since there are 2 terms in the expression. Now consider the expression

Quite obviously

Here, on the right side of the equation, there are n sets of parentheses, reflecting the power n on the left side of the equation. Now we have to ask ourselves how we expand the right side. When we expand, we have to select one of the terms, either a or b, from each of the binomial terms. We could select a from all the binomial terms, leading to an. Or we could select b from all the binomial terms, leading to bn.

In general, if we select b from r of the binomial terms, this would mean we have selected a from the remaining n-r binomial terms, leading to an-rbr. In how many ways can we form the an-rbr term? This will be the same number of ways as selecting r out of n items, since, when we select r of the binomial terms to give us b, we will be auto-selecting the remaining n-r binomial terms to give us a. Hence, the binomial expansion gives us

Hence, we can conclude that

With special note are the first two terms. The first term is

Similarly, the second term is

Hence, the expansion can be expressed as

Now, all the terms that are in red are the product and quotients of natural numbers. Hence, each term is necessarily positive. This allows us to conclude that

Hence, we have obtained the lower bound for e. All we need now is to obtain the upper bound. This is somewhat more difficult. We first need to demonstrate that f(n) is an increasing function.

f(n) is an Increasing Function

Let us consider the two consecutive terms f(n) and f(n+1). We have

Taking LCM inside the parentheses, we get

Dividing the second equation by the first we get

This can be further modified to give

Choosing a new index m = n+1, the above gets transformed to

This can further be written as

Now consider consecutive terms in the expansion of the term in red above.

Dividing the second equation by the first we get

It is clear that the two terms in red will cancel. At the same time, the green terms will leave r+1 in the denominator, while the blue terms will leave m-r-1 in the numerator. Hence, the above simplifies to

Redistributing the terms and taking absolute value so we do not have to deal with a negative quantity, this is equivalent to

Since r takes values from 0 to m-1 and since m must be necessarily greater than or equal to 2 (remember m=n+1), each of the three terms above is strictly less than 1. Hence, in the expansion

each term has a smaller magnitude than the preceding term. If we write out the expansion we get

Now we have shown that the 3rd term (in red) has a greater magnitude than the 4th term (in green). Hence, the sum of the 3rd and 4th terms must be positive. Similarly for each subsequence pair of terms in the expansion. If m-1 is even, there will be an odd number of terms in the expansion, with the final term being positive. If m-1 is odd, there will be an even number of terms with the final pair of terms also yielding a positive sum. Hence, we can conclude that

However, recall that

This means that

This means that f(m) is increasing, which also means that f(n) is increasing.

Whew! That took some doing, huh?

Combining the Limit Process and the Binomial Expansion

What we can now say is that f(n) will keep getting larger as n gets larger. Recall that we had shown

This means that

if both limits exist. Now since f(n) keeps increasing, all we need to show is that there is some upper bound beyond which the expansion cannot go. That would also place an upper bound on the value of f(n).

Introducing an Infinite Geometric Series

Consider the infinite series

Here each term is multiplied by ½ to get the next term. If we multiply the whole equation by 2 we get

However, note that the terms in red are the same series with which we started. This gives us

Obtaining the Upper Bound for e

Now once again consider the expansion for f(n), which is

Now the (r+1)th term is given by

Note that this happens to be the rth red term above and it can be modified as follows

Rearranging the terms we get

Some more rearrangement gives

Here, r varies between 0 and n. Hence, all the terms in red are necessarily positive and less than 1. However, in the limiting case, as n approaches infinity, the limiting value of each of the red terms is 1. This gives us

Writing the infinite series this will give us

For the fourth term onward, r is greater than or equal to 3. However, it is easy to see that for r > 2

As examples

Hence, we can conclude that

However, we have already shown that the terms in red add up to 2.

Hence, using the earlier lower bound result, we conclude

Conclusion

We have shown that the value of e lies between 2 and 3. Along the way we used some mathematics that we had explored earlier, like reductio ad absurdum and the method of determining the number of ways of selecting r out of n items. But we also introduced new mathematics, like the limiting process, the binomial expansion, and the infinite geometric series. The crucial step was to show that f(n) is increasing. If this were not true then showing that it has a lower and upper bound would not indicate that there is a specific value to which f(n) approaches, since it could then just oscillate between slightly above 2 and slightly below 3. The process to demonstrate this was considerably involved and also included the idea of showing that successive pairs of a sequence added to give a positive sum. This was not necessarily the most intuitive step in the process, even though, without it, we would not have been able to prove the result.

In the previous post, we introduced e and touched on what its significance is and why it is the base of the ‘natural’ logarithmic and exponential functions. In this post we have placed bounds on the value of e. Since this post end up being quite long and, I must admit, heavy, I am going to do a part of what I planned for this post in the next, where we will look at some common infinite series that have been derived for e and consider how rapidly each of these series converges to the actual value of e. In the post after that, I will deal with how we know that e is irrational. I will, however, be taking a break next week. Hence, the next post on infinite series for e will be published on Friday, 7 June 2024.

Leave a comment