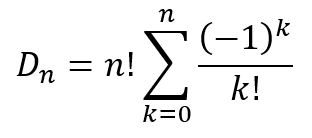

In the last three posts, we have been dealing with some issues related to counting. In Learning to Count, I introduced us to the area of combinatorics and specifically combinatorial arguments. In the second post, Abjuring Double Counting, we looked at the inclusion-exclusion principle that is used to ensure that every element is counted exactly once. In last week’s post, No Place at Home, the third in this series, we looked at the idea of derangements and used the inclusion-exclusion principle and a recursive formula to derive the expression for the number of derangements in a set of n items. To jog your memory, we proved that

Revisiting an Old Friend

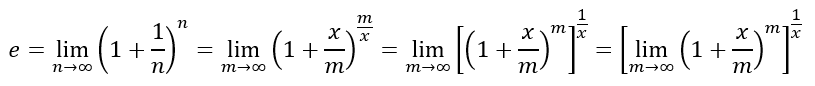

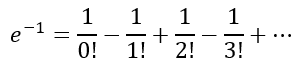

In the previous series of posts, we had dealt with the number e. In the second post in that series, Naturally Bounded, we had derived an infinite series expression for e as

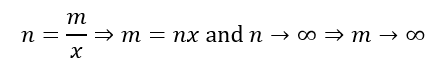

In the above equation, we make the following substitution:

This gives us

Please read the above carefully. Raising the equation to the power x we get

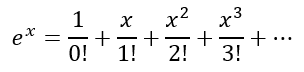

Using the same techniques as we used in Naturally Bounded, we will obtain

If we substitute x=-1 in the above we will get

A Surprising Result

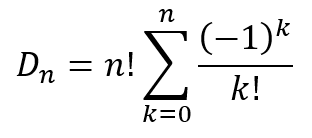

Now consider the equation

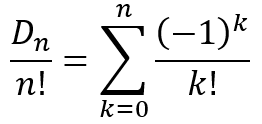

We can rewrite this as

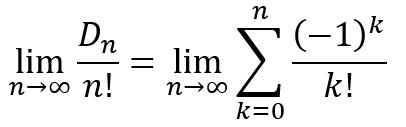

Taking a limit on both sides as n approaches infinity, we will get

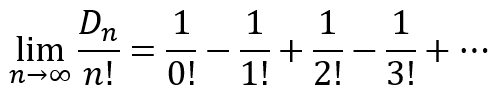

Expanding the summation on the right side we will obtain

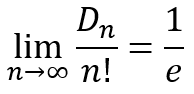

But we just showed that the right side is related to e. Specifically, we can write

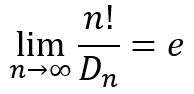

Or taking reciprocals we get

In other words, as n increases, the ratio of the number of permutations of n items to the number of derangements of the n items approaches e. This is a surprising result as there is no obvious reason for which e should show up in this ratio.

An Approximate Explanation

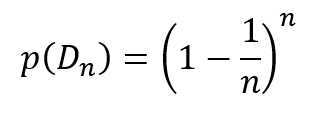

However, let us consider that we have a set of n items. If we now place items in random positions, the probability that item 1 occupies its own spot will be 1/n. Hence, the probability that it does not occupy its own spot will be 1-1/n. The probability that item 2 occupies its own spot will be 1/(n-1), since one spot has already been occupied by item 1. Hence, the probability that item 2 is not in its own spot is 1-1/(n-1). For large values of n, 1-1/n and 1-1/(n-1) are nearly equal. For example, if n=1,000,000, the corresponding values are 0.999999 and 0.999998999998…, where the difference is approximately 0.000000000001. Since the probability values are so close to each other, we can approximate the probabilities that each of the n items to not occupy its own position to be 1-1/n.

This leads us to the overall probability being

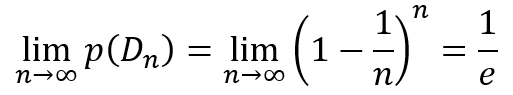

Taking the limit as n approaches infinity we get

So we can see that the reason e appears in our study of derangements is that, for large values of n, the placement of the items in positions not their own are almost independent of each other and almost equal to each other. That we have used the word ‘almost’ twice is the reason why e only shows up in the limiting case and not for any finite values of n. Of course, as we place more items in different positions, the error involved in the approximation will increase. Hence, the above reasoning cannot fully account for the appearance of e in the expressions about derangements.

Hidden in Plain Sight

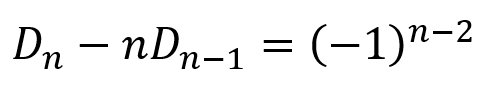

However, recall that, in the previous post, we had derived

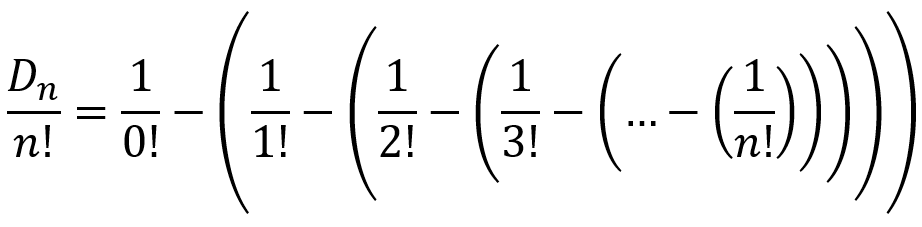

If we divide throughout by n!, we will get

This reduces to

The term in red is the probability that a random permutation of n items is a derangement. The term in green is the probability that a random permutation of n-1 items is a derangement. We can see that as n gets larger, the right side gets closer to zero at the rate of a factorial. Hence, we can conclude that the two probabilities on the left side converge to some specific value.

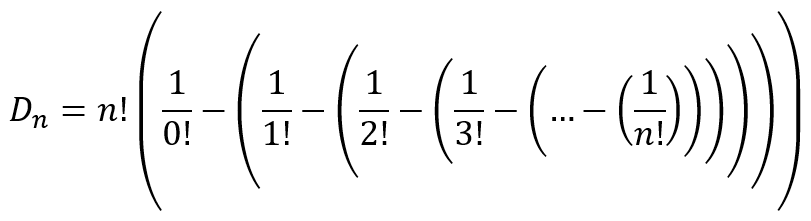

Further, we had derived the expression for the number of derangements as

which can be rearranged to give

As observed in the previous post, the nesting of the parentheses yield the alternating signs of the terms. We also saw that the nesting of the parentheses was the result of the application of the inclusion-exclusion principle. In other words, the alternating signs are the result precisely of the way the derangements are counted. Hence, even though we might not have expected the appearance of e and might even be quite surprised by it, it is actually something that was in the expression all along.

Deranged No More

I have enjoyed writing these posts on counting, especially the last two on derangements. When I first encountered the idea, it was a novelty. Why would we ever want to place something where it does not belong? Being a person who does like order (though you may not suspect it if you looked at my desk!), the thought of placing something where it did not belong seemed only to be an instance of mathematicians playing around. But, as we saw in the previous post, derangements have a wide range of applications, some not quite intuitive. My interest was further piqued when I first saw how derangements are linked to e. The startling result hammered home the idea that mathematics, though often divided into incommensurate silos while we are taught it in school, is actually a unified body of knowledge.

I hope you have also received some enjoyment and maybe some stirring of interest through these posts. I would really like to hear from you. Please do write a comment and let me know what you liked, what you disliked, and what you found confusing.

Leave a reply to Anticipating the Exponential Whirligig – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply