Coming Back Full Circle

This is the final post in this series of posts on π. We began with A Piece of the Pi, where we looked at the early ways of approximating the value of π based on circumscribing and inscribing a circle with regular polygons. We saw that this method, while perfectly sound, had two drawbacks. First, it only provides upper and lower bounds for the value of π rather than an actual approximation of the value. Second, the method converges extremely slowly. This was followed by Off On a Tangent, in which we introduced infinite series Machin-like methods based on the inverse tangent functions. This was followed by The Rewards of Repetition, in which we introduced iterative methods used to approximate the value of π. Last week, we looked into the Gauss-Legendre algorithm, which is a powerful iterative method. In this post, we move toward some methods that are used more commonly for the purpose.

Efficient Digit Extraction Methods

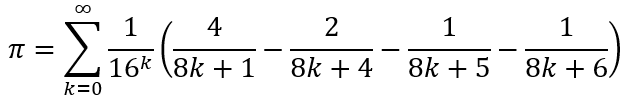

Efficient methods for approximating π often are based on the Bailey-Borwein-Plouffe formula (BBP) from 1997, by David Bailey, Peter Borwein, and Simon Plouffe, according to which

Right away, we can see the strangeness of this formula. There seems to be no rationale linking the four terms in the parentheses, nor any indication for why the formula includes the 16k factor in the denominator.

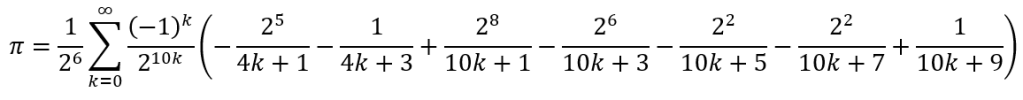

This was later improved upon by Fabrice Bellard’s formula, according to which

It is clear that things have gotten stranger than before! However, Bellard’s formula converges more rapidly than does the BBP formula and is still often used to verify calculations.

The advantage of the BBP and Bellard methods is that they converge so rapidly that there is hardly any overlap between the digits of terms. This allows the calculation to be started at a higher value of k than 0 in order merely to check the last string of digits of π than the whole string. After all, if we have previously checked a certain formula for accuracy till 1,000,000,000 digits, then the next time we generate digits using the same formula, we need only to check the digits from the 1,000,000,001th digit.

This advantage of the BBP and Bellard formulas makes them particularly suited for this digit check. Due to this, they are often categorized as efficient digit extraction methods.

Ramanujan Type Algorithms

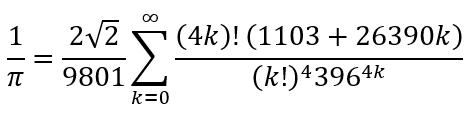

Despite that rapidity with which the BBP and Bellard formulas converge, they are not used today to calculate further digits of π. This is because from Ramanujan we have the infinite series approximation

which converges even more rapidly. This is a very compact formula. Yet, almost all the elements of the formula (√2, 9801, (4k)!, 1103, 26390, (k!)4, and 3964k) are, if we are being honest, weird. Only perhaps the 2 in the numerator can be considered as not weird. Even the fact that this series gives us approximations for the reciprocal of π rather than π itself is strange since this does not function as series that give us approximations for π. In particular, since it approximates 1/π, it cannot be used for digit checks like the BBP and Bellard formulas. However, it is precisely because the series gives the reciprocal of π that it converges much more rapidly than the BBP and Bellard formulas.

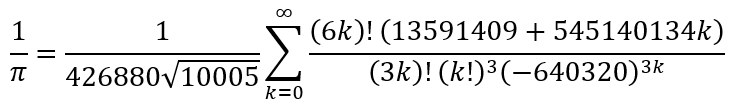

In 1998, inspired by the Ramanujan formula, the brothers David and Gregory Chudnovsky, derived the formula

Here, every single element is weird! However, the Chudnovsky algorithm converges so rapidly that each additional term gives approximately 14 additional digits of π. If you are interested you can find the 120 page proof of the Chudnovsky algorithm here.

The Chudnovsky algorithm is so rapid that it is the one that has been used often since 1989 and exclusively since 2009. The results are checked by the BBP and/or Bellard formulas. On Pi Day 2024 (i.e. March 14, 2024), the Chudnovsky algorithm was used to calculate 105 trillion digits of π. Just over three months later, on Tau Day 2024 (i.e. June 28, 2024), the calculation was extended to 202 trillion digits.

Forced to Compromise

Despite the rapidity of the Chudnovsky algorithm, it is the Gauss-Legendre algorithm that actually converses more rapidly. However, after April 2009, the Gauss-Legendre algorithm has not been used, the final calculation on 29 April 2009, yielding 2,576,980,377,524 digits in 29.09 hours.

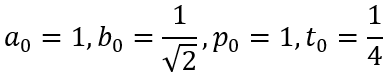

If the Gauss-Legendre algorithm is more rapid, why is it not used anymore? Let us recall the algorithm. The Gauss-Legendre algorithm begins with the initial values:

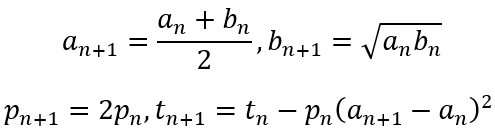

The iterative steps are defined as follows:

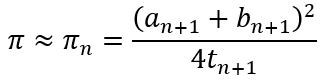

Then the approximation for π is defined as

So at each step, we need to have an, bn, pn, and tn in memory, while an+1, bn+1, pn+1, tn+1 and πn have to be calculated. Once this latter set has been calculated, the former set has to be replaced with the latter set before this can be done. The calculation done in April 2009 used a T2K Open Supercomputer (640 nodes), with a single node speed of 147.2 gigaflops, and computer memory of 13.5 terabytes! By contrast, the December 31, 2009 calculation using the Chudnovsky algorithm to yield 2,699,999,990,000 digits used a simple computer with a Core i7 CPU operating at 2.93 GHz and having only 6 GiB of RAM. The difference in the hardware requirements and consequent costs are so large that recent calculations have used the less efficient Chudnovsky algorithm rather than the more efficient Gauss-Legendre algorithm. So it seem that even mathematicians have to climb down from their ivory towers and confront the banal realities of the world!

Leave a comment