Tools that Help

There are tools that enhance one’s ability to understand. And there are tools that are a hindrance to understanding. For example, when I first came across a Phillips head screw and the screwdriver that accompanied it, I was blown away. I was intuitively able to see why this screw head was superior to the regular flat screw head. And I was intuitively able to understand why the screwdriver was shaped the way it was.

I experienced a similar sense of euphoria when first paito the tables of logarithms and antilogarithms. I was able to see that the numbers in the logarithm tables increase rapidly at first before tapering off to a crawl, while, in the case of the antilogarithm tables, it was the reverse, starting at a crawl and speeding up exponentially. Hence, when my teacher later told me that the antilogarithm function is actually the exponential function and that the exponential function and logarithm function were inverses of each other, I had already intuitively grasped it through years of poring over the tables.

A Tool that Hinders

One tool, however, that is actually a hindrance to student learning is the calculator. As a mathematics teacher, I loathe calculators because they obscure the calculations that they perform and because they do not allow the student to see the larger picture of mathematical beauty and reality. For example, it is almost impossible for any student using a calculator to realize that the logarithms begin with rapid increases and then taper off, something that a couple of intentional glances at the tables would readily make evident to the same student.

Similarly, the periodicity of the trigonometric functions, something that is easily grasped through the simplicity of the unit circle, is rendered quite opaque when a student uses a calculator. Moreover, if a student obtains 0.78539816339 or 2.09439510239 as the answer to a trigonometry question, it is all but impossible for the student to realize that the first answer is actually π/4 and the second 2π/3. Given that these are important angles in geometric and trigonometric settings, including the setting of complex numbers, the obscuring of these angles is detrimental to the student’s learning.

In a similar way, the calculator may easily give answers like 0.36787944 or 0.69314718056, but if the student doesn’t recognize these as 1/e and loge2, something crucial is lost in terms of mathematical understanding.

What the calculator does is elevate a decimal representation of numbers over all others. For example, calculators regularly give the first few digits of the decimal representation of irrational numbers. So, for example, π will be given as 3.14159265359 or something like that, depending on the number of display digits the calculator may have. Similarly, the square root of 2 may be given as 1.41421356237. However, what the calculators do not tell the user is that these are only the first 12 digits of the decimal representation of these irrational numbers and that this representation continues indefinitely and without patterns.

At the same time, students are introduced to ways of representing rational numbers in decimal format. Hence, students are taught how to show that 1/7 = 0.14285714285. And they are taught to do the reverse. Hence, they know how to demonstrate that 0.25 = 1/4.

With the calculator display misleading the students by obscuring the fact that the number is irrational, students often do the reverse process and conclude that, since the calculator shows only 12 digits, this must mean that the decimal representation of π either terminates at the twelfth digit or repeats in some pattern after the twelfth digit. But this would mean that π is a rational number!

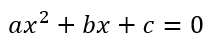

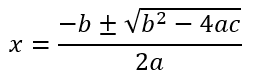

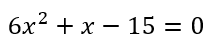

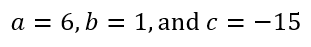

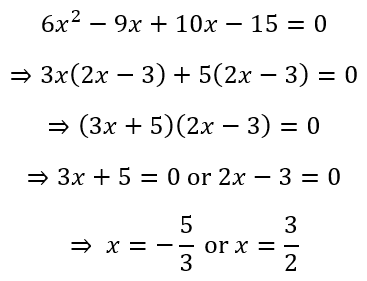

The problems with calculators are compounded when we actually get to solving questions. For example, by the time students reach the ninth grade, they are introduced to quadratic equations and are told that the roots of the equation

are

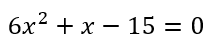

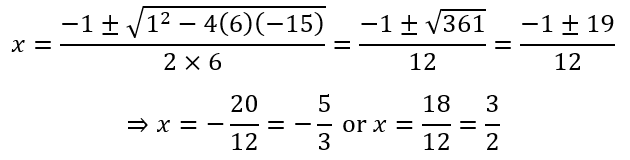

Now let us say the student is asked to solve the equation

From this equation the student will be able to obtain

Then she can plug the values of a, b, and c into the calculator to get

Actually, most calculators would give -1.66666666667 and 1.5, but I’m presuming the student is astute enough to know that these are rational numbers.

The presence of the calculator makes the student reach for it, if she has become used to using it, much like an addict would reach for his next fix. And she would reach the correct answers if she pushed the right buttons. However, by doing this, the student has lost an opportunity to learn something more about number patterns. Give then equation

where

we want two integers whose product is

and whose sum is

We can proceed by listing pairs of factors of -90 that multiply to give -90 and then check to see which pair also gives a sum of 1. This would give us

A quick glance at these pairs would reveal that -9 and 10 are the numbers we need. This allows us to split the middle term and factorize as follows:

The insights that two integers have a product of -90 and a sum of 1 and that the factors of the equation are 3x + 5 and 2x – 3 are totally obscured by the calculator. The greater insight that, if the product of two numbers is zero, then one of them must be zero is completely lost when we use the calculator.

Calculators and Computational Engines

Calculators have developed a lot since their now clearly humble beginnings as four function calculation devices. Not only do we have scientific calculators and the more advanced graphic display calculators, but also we have some calculators that can perform highly sophisticated symbolic manipulations. They are in effect hand held computational knowledge engines.

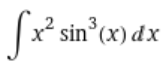

I do not doubt nor wish to disparage the ingenuity of the people who have brought us to the stage where anyone can make an inquiry about a mathematics problem and get not just the answer, but also a step by step solution. For example, if you ask WolframAlpha to determine

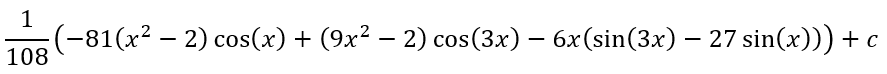

it will churn out

as the answer in a fraction of a second. If you have a paid subscription, it will even give you the full sixteen step solution, where each step actually consists of sub-steps!

But what have I gained by using WolframAlpha? I have obtained an answer to a reasonably involved question of integration, but I have not advanced my own understanding of integration nor of even more banal mathematical concepts like the addition of fractions. I have not learned how the trigonometry and the algebra interrelate in this question.

Now place a similar, but lighter version, of this computational knowledge engine in the hands of a student in an exam. If the exam authorities do not permit the use of the symbolic manipulator, the student will have to place the calculator in exam mode. So what was the use of having this feature in the calculator? Absolutely none! But suppose the exam authorities do not have such restrictions. Then the student can simply use the symbolic manipulator to solve the questions. What then did the exam test except whether the students knows which buttons to press and in which sequence?

Computational knowledge engines, in my view, showcase the wonderful human ability to program something as lifeless as a circuit to emulate human behavior in computational situations. However, as a learning tool, they fall abysmally short. Showing a solution, as WolframAlpha does, is not the same as teaching. As the solution reveals, there is not even the slightest attempt made to give a rationale for any of the steps, which is the essence of teaching and learning.

Reneged Responsibility

Calculators and computational engines, in my view, are worse than crutches to a student of mathematics. They deceive the user into thinking that he/she has accomplished something grand, when in fact all he/she was was functioning as a glorified button pusher. Unfortunately, humans have never shown the ability to decide whether our ability to do something means that something ought to be done or not. And it is here that our educators have failed us as well. Just because we have machines that can do certain tasks, does not mean we have to depend on them for doing those tasks. Indeed, if those machines are robbing us of some ability we should be quite circumspect about bringing those machines into our learning spaces.

However, most educators in the world want to jump onto the technological bandwagon. We have surrendered our responsibility of curating what students should be exposed to in our classrooms and have allowed the wider world to dictate to us. Just a while back I realized that some of my students did not even know the names of the components of a geometry set, let alone know how to use them. Yet, they knew very well how to push buttons on a calculator. However, the geometry set develops a student’s hand-eye coordination, his/her fine motor skills, and his/her dexterity, while also inherently bridging the two hemispheres of the brain in a single activity.

The calculator does none of this. Yet, we have privileged these electronic machines in our classrooms, depriving our students of invaluable learning experiences. It is a shame. It is time educators put their feet down and acted as what they truly as – custodians of our future knowledge. It is time we stopped our slavish dependence on technological innovation just for the sake of it and actually ask whether any innovation actually furthers student learning before allowing something new into the classroom.

Mind you, I am not someone who is averse to technological developments. I readily adopt new technologies. However, as a teacher, I have to prioritize what will enhance the learning of my students above any other factor, including especially the lure of staying technologically current. If some technology hinders student learning, as I firmly believe calculators and computational engines do, then it is my responsibility to make my voice of opposition to them heard even if it means alienating myself from teachers who hold differing views.

Leave a comment