The Presenting Problem

In response to the previous post, in which I had categorically declared that the use of calculators in mathematics education is a hindrance to students, a former student asked me, “Do you think it would be feasible or even beneficial to move mathematical assessments from the current manipulation & computation to something that focuses more on formulation and derivation from first principles from a given context (similar to IB DP AA HL paper 3)?”

To decipher the last few characters of the student’s question, ‘IB‘ stands for International Baccalaureate, ‘DP‘ for Diploma Programme, ‘AA’ for Analysis and Approaches, and HL for Higher Level.

In what follows, I will be addressing specifically what the IB does. However, this should not be taken as a critique of the IB alone, but of all the major exam boards around the world, like CAIE, Edexcel, AP, CBSE, and CISCE, just to name a few international and Indian boards. If you are reading in a country other than India, the UK, or the USA, please think of the exam boards that exist in your country.

What is Paper 3 Like?

Anyway, returning to my student, he was asking if I thought that the kind of questions that often appear in paper 3 for that syllabus would be something I considered ‘feasible’ and ‘beneficial’. Of course, many of you may be in the dark about what kind of questions might appear in this paper. If so, please click here to be taken to one example of paper 3.

If you read the paper, you will discover the following:

- The question paper consists of 2 questions for a total of 55 marks and a duration of 1 hour.

- The first question is worth 27 marks and combines geometry, sequences and series, and mathematical induction.

- The second question is worth 28 marks and combines polynomials, complex numbers, coordinate geometry, and calculus.

As someone who loves mathematics, I must concede that I do find the Mathematics AA HL Paper 3 to be quite an interesting ‘animal’. As just mentioned, it gives the student problems in which different areas of mathematics are made to relate to each other. While the situations are contrived, the student is exposed to the possibilities that a little imagination can introduce to us.

Zoning Problems

Now, the IB has different papers for different time zones. In time zone 2 the students would have received this paper. If you read the time zone 2 paper you will discover the following:

- The question paper consists of 2 questions for a total of 55 marks and a duration of 1 hour.

- The first question is worth 28 marks and combines coordinate geometry, functions, and calculus.

- The second question is worth 27 marks and combines polynomials, theory of equations, and complex numbers.

You may be wondering, “So what?” Of course the papers have to be different. Otherwise, the IB would not be able to administer different papers in different time zones, thereby risking the security of the question papers. And I fully agree.

But note that the time zone 1 paper has a significant number of marks devoted to mathematical induction, while the other one has marks devoted to the theory of equations. Mathematical Induction is a stand-alone topic that is somewhat weird to boot. So many students often decide to skip it and hedge their bets on it not being tested for too many marks. Theory of equations on the other hand is an integral part of mathematics and links with many other topics.

So consider four students, P, Q, R, and S. P and Q write exams in time zone 1, while R and S write in time zone 2. P and R regularly get a grade of 7 (the highest possible), while Q and S are borderline between 5 and 6 and have both chosen to ignore mathematical induction. Q, having ignored mathematical induction, will have a low score in paper 3 because he is writing a paper that tests that topic, while S, who also ignored the same topic, will not be affected since she is writing a paper that does not test that topic. P and R are not affected negatively in terms of their raw score. However, there will be little to distinguish between R and S since both are writing tests that do not include topics that S chose to ignore. Since many students writing exams in time zone 2 might have ignored mathematical induction without being negatively affected, the grade boundary for a 7 in time zone 2 will rise, thereby disadvantaging student R, who, for no fault of his own, is clumped with student S, who had hedged her bets. So what we have is some students, like S, in time zone 2 being unfairly favored, while others, like R, being unfairly disfavored.

The Problem of Grade Descriptors

Of course, the IB, like many exam boards around the world, claim to assess students on the basis of grade descriptors. But this is a hoax. There can be no grade descriptors when we are assigning final grades based on some numerical grade boundaries. If it were actually possible to relate grade descriptors to grade boundaries, we would actually not need both because everyone would automatically know how to translate from one to the other.

You see, I have experience marking IB mathematics exams and internal assessments. I know the difference between the two. The internal assessments are indeed marked according to a set of grade descriptors for each assessment criterion. However, the exam papers are not. In fact, if we are being honest, it is impossible to have a rigid mark scheme and also grade according to student achievement based on grade descriptors. You can do one or the other. You cannot do both. And the hoax that exam board the world over attempt to make us believe is that it is possible to do not just both, but also to be fair to all the students.

You see, the very idea of numerical grade boundaries that are determined after the exams are written and graded is that there is a post hoc determination of what separates the 6 from the 7. Why is this a fallacious approach?

The Problem of Grade Boundaries

It is impossible for every question to assess the student on every criterion. In other words, question 1 may assess a student on criteria A, B, and C, while question 2 may assess a student on criteria B, D, and E. However, when we say there is a grade boundary, we are saying that only the final mark matters and not where the student earned the mark. Hence, if criterion C is weighted more heavily than criterion D and E, then the student who gets a total of 40 marks with 25 marks question 1 and 15 in question 2 should receive a higher grade than a student who scores 15 in question 1 and 25 in question 2. All this is ignored when we assign grade boundaries based solely on the raw score.

What I am saying is that, for all their claims to assign grades based on some assessment criteria, the major exam boards are doing nothing of the sort. They have some highfalutin jargon that confuses people and dupes them into thinking the boards are actually assessing the students on criteria rather than relative to others. You see, what we all want is to know what a student has achieved because that tells us how much the student has learned. We do not want to know how she did relative to others because that tells us very little about her own learning. After all, if she is in the 95th percentile when the average was 50 with a standard deviation of 10, then her raw score would be 66, meaning that she has ‘mastered’ about two-thirds of the syllabus. However, if she is in the 90th percentile when the average was 70 with a standard deviation of 8, then her raw score would be 80, meaning that she had ‘mastered’ more than four-fifths of the syllabus. However, since the grade boundaries are based on the performance of the cohort, the board will determine that only a small fraction, say 8%, of the students should get the highest grade. Hence, the student who had only ‘mastered’ two-thirds of the syllabus would get a grade of 7 while the student who had ‘mastered’ four-fifths (i.e. 20% more) would get a grade of 6. You can check my working using the online inverse normal calculator here.

In other words, assigning grades based on numerical grade boundaries does precisely what the major international exam boards tell us they are not doing, that is assigning grades in a relative manner. If the grades are indeed criteria based, how is it that the criteria map so perfectly onto the raw marks that students achieve? Further, the practice of having different papers for different zones may mitigate against candidate malpractice for sure. But it seems it opens the door to ‘exam board malpractice’, something no one wishes to talk about! When I say ‘exam board malpractice’, I mean the practice of equating two things that appear equivalent only in the eyes of the exam board, but not to the students. If the exam boards are serious about grading the students on the basis of assessment criteria, then it is imperative that they move away from exam focused assessments.

The Proposed Revolution

Mind you, this is not the case of sour grapes. I am an exceptionally good test taker. And I have done well as a teacher to prepare my students not just with the knowledge to succeed at exams but also with the mental resilience that exams need.

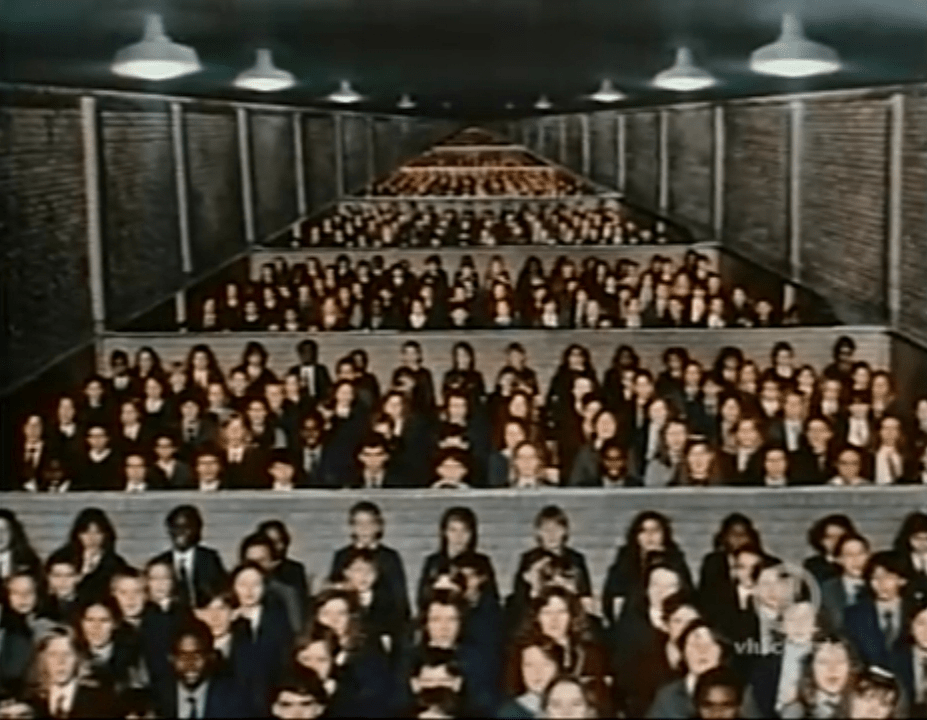

However, for more than two decades now I have found that exams are dehumanizing. Yes, I have used a strong word. But I do this because no one ever finds themselves in ‘exam conditions’ outside school. The exam rooms are made pristine and silent, thereby placing at a disadvantage students who thrive in situations of controlled chaos and those who like to listen to music as they learn. Movement is prohibited, thereby disenfranchising those students who like to think as they walk or dance. Food is forbidden even though some students like a regular calorie burst to stimulate their minds. Everything that makes us human – food and movement and music – are forbidden from the exam room. Rather, the only acceptable involvement of the body is to hold a pen and move it along a piece of paper, something that humans have been doing only for the last 1% of their existence on this planet. The exam room forces humans to become just a bodiless head moving a torsoless hand. Exam rooms suit people like me – those who are able to concentrate in quiet environments and who are able to be seated for long stretches of time and who can go without food for ages.

Teaching and learning is a local affair. Even in this age of online classes, there is a ‘proximity’ of the student and the teacher. Exams strip the student of this support structure even though, in every job I can think of, one is free to consult with a more knowledgeable colleague or a mentor. Further, except in the most time sensitive jobs, one always has the freedom to ask for an extension, something that the very nature of an exam precludes.

But if teaching and learning are local affairs why should the assessment of learning not also be predominantly a local affair between a teacher and a student? That was how it was before the Industrial Revolution made us accept the production of graduates on an assembly line. That was how is was before we decided that large exam boards were better at gauging a student’s learning than the teachers who had taught the student.

I think it is time for a revolution in education. It is time we reaffirmed the agency and responsibility of the teacher not to teach to some predetermined syllabus but to teach what is relevant for the student’s plans and hopes for his/her future in accordance with the unique skills and talents and proclivities of each student in her/his care.

Leave a reply to Udit Cancel reply