Order! Order!

As a mathematics teacher, I primarily teach students in high school, preferring, within this group, to teach grades 11 and 12. There are two reasons for this. First, mathematics taught in grades 11 and 12 is complex enough to allow for interesting nuancing of the ideas and also blending of the various areas like algebra, geometry, trigonometry, statistics and probability, and calculus. Prior to that the concepts are too superficial to allow for such unrestrained exploration. Second, I really do not know how to handle students who are younger than 14.

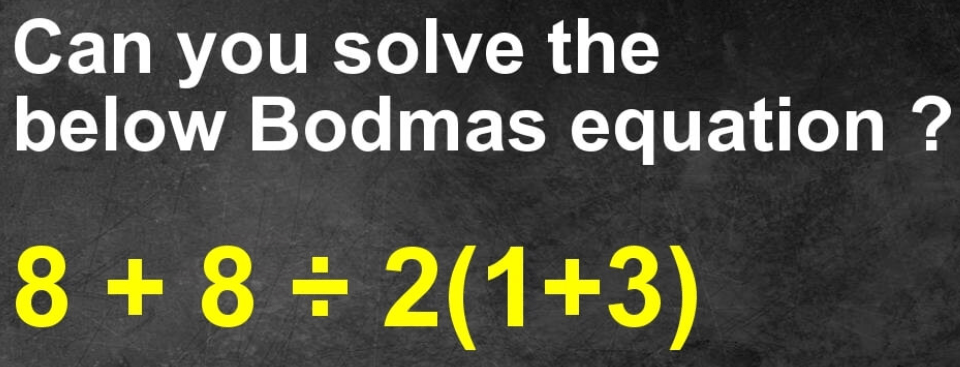

Anyway, one year I was feeling somewhat adventurous and agreed to teach students in grade 6. This was the academic year 2016-2017. The kids were, as expected, difficult to handle. However, what I was surprised with was the fact that most of them were very weak with order of operations. For those of you who are confused about this terminology, perhaps BODMAS or PEMDAS or some such six letter variation might prove to be a reminder.

In the above, ‘M’ stands for ‘multiplication’, ‘D’ for ‘division’, ‘A’ for ‘addition’, and ‘S’ for ‘subtraction’. Those are the letters that do not change, even though D and M often swap positions. We will see why shortly. However, the first two letters have some variety. The first letter varies between ‘B’ for ‘brackets’, ‘P’ for ‘parentheses’, and ‘G’ for ‘grouping’. The second letter varies between ‘O’ for ‘orders’, ‘E’ for ‘exponents’, and ‘I’ for ‘indices’. So, we can get 18 variations of these letters, all of which essentially give the same sequence for performing operations. However, whether we call it BODMAS or PEMDAS or GIDMAS, whatever does it mean? And, more importantly, why do we have such an ordering?

Mathematics aims for consistency. In other words, if 2 people perform the same set of operations accurately, we expect them to obtain the same answer. We will see how this desire for consistency is at the root of BEDMAS. I will use BEDMAS because I think ‘O’ for ‘orders’ is weird since we never call the exponentiation operation by that name anywhere else. Also, ‘G’ for ‘grouping’ is vague and is also not common terminology. So how does BEDMAS give us the consistency we aim for?

Testing for Consistency

We begin with the most basic operation – addition. And we know that 2 + 3 and 3 + 2 gives us 5. We call this property the commutative property. Hence, we say that addition is commutative. This means that, given any two numbers, say a and b, a + b = b + a. When we consider subtraction, however, we get a different result because 2 – 3 is not the same as 3 – 2. In fact, the first is -1 while the second is 1. We can actually generalize this to say that a – b and b – a are negatives of each other. We often say that subtraction is anticommutative.

When we move to multiplication and division, we see quite similar things. For example, we realize that multiplication is commutative because a × b = b × a. However, we say that division is noncommutative because a ÷ b and b ÷ a are not negatives of each other but reciprocals of each other.

We have, therefore, seen how the four basic operations function. Now we have to ensure that our sequence of operations maintains this feature.

So let us consider 2 + 5 × 3. Since we normally perform operations from left to right, let us do this here. Let us also give preference to the addition operation and perform it before multiplication. With this approach, we will first add 2 and 5 to get 7 and them multiply by 3 to get 21. However, we know that addition is commutative. Hence, if it was true that we should do the addition first, we should get the same answer if we did 5 + 2 × 3. This does prove to be the case. However, we know that multiplication is commutative. So swapping the 3 and the 7 (from 2 + 5 or 5 + 2) should give us the same answer. Now we have 3 × 2 + 5. But this gives us 6 + 5 = 11. And if we swap the 2 and 5 we have 3 × 5 + 2, which gives us 17.

Since we are getting different answers with different approaches, let us now give precedence to multiplication over addition. Hence, if we are given 2 + 5 × 3, then we need to perform the multiplication first, to get 2 + 15, which then gives us 17. But again, we recognize that addition is commutative. So, we could write 5 + 2 × 3, which gives 11 if we perform the multiplication first.

What we can see is that there is no sequence that is inherent to the operations themselves. After all, multiplication itself is ‘repeated addition’! So one would not expect anything inherent to the two operations than can actually make a distinction between them.

An Alternate Convention

But what this means is that we need to decide upon a ‘convention’ that all of us will follow, which will remove the ambiguity concerning which operations need to be done first and which ones last.

For example, we could propose an alternate order, namely SAMD, just for the four primary operations. Then if we have to calculate 4 – 5 × 6 + 8, we would perform the subtraction first, to get -1 × 6 + 8. Then we would perform the addition, resulting in -1 × 48. Finally, we would perform the multiplication to get -48. Similarly, if we had 6 – 2 × 3 ÷ 4, we could get the following steps 4 × 3 ÷ 4 = 12 ÷ 4 = 3. As long as everyone followed the convention we would all get the same answer all the time.

The Need for Conventions

Conventions are crucial in any area of knowledge. For example, in the sentence, “The cat climbed the tree” it is only by convention that we accept that ‘the cat’ is the subject of the verb ‘to climb’, which ‘the tree’ is the object. There is nothing inherent to the order of the words that tell us this. That is why in many languages, the adjective comes after the noun it qualifies, while in English it comes before.

Similarly, in chemistry we may come across the symbol Na2CO3. Only convention tell us that Na represents Sodium, C represents Carbon and O represents Oxygen. Only convention tells us that the subscripted 2 and 3 indicate the number of atoms of the element preceding it that constitutes the molecule.

The same is true about mathematics. The symbols do not interpret themselves. We need to accept conventions that everyone agrees to follow in order to communicate mathematical knowledge reliably.

Unfortunately, most of us mathematics teachers do not recognize the complete arbitrariness of the order of operations since we have become so used to the convention that we cannot see it as arbitrary. However, as I have attempted to show, mathematicians could have adopted another convention for the order of operations without there being any confusion. I think that, if mathematics teachers spent some time asking students to arrive at a new convention they could follow for a time, it might be a good exercise in helping students realize that there is a consensus that has been adopted, which everyone needs to follow so that we can communicate mathematical ideas reliably and without confusion.

Leave a comment