The Presenting Problem

Recently I came across a video on YouTube that asked the question, “Which is bigger: 99! or 5099?” There are so many such questions on YouTube and I wonder why. After giving it some thought, I realize the truth in the saying, “Give a woman a fish and you feed her for a day. Show a woman to fish and you feed her for a lifetime.” Ok, fine, the original had ‘man’ instead of ‘woman’! But you get the point. When we teach people how to solve a particular problem rather than show them the principles that would enable them to solve problems in general, we are giving them a fish that will last them a day.

So I’m going to treat problems like this under a single umbrella. You see, the question could have been, “Which is bigger: 101! or 51101?” or “Which is bigger: 199! or 100199?” and the approach would have been exactly the same. Since I’m saying this, try to determine a pattern in the numbers involved in each of the questions before you proceed.

The Pattern

What we should be able to see in the pairs {99! 5099}, {101! 51101}, and {199! 100199} is that the number whose factorial forms the first part of the pair shows up as the exponent in the second part of the pair. And these are odd numbers. Also, the base in the second part is half of one more than the exponent (50 = (99 + 1)/2, 51 = (101 + 1)/2, and 100 = (199 + 1)/2). So we can generalize the question to, “Which is bigger (2n-1)! or n(2n-1).

Breakdown

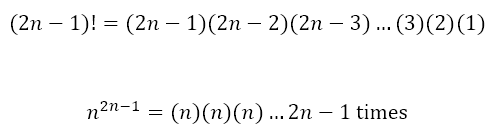

We can recognize that (2n-1)! and n(2n-1) are each the products of 2n-1 numbers. Hence,

Now, the middle number in each product is n. Moreover, the sum of the first and last terms in each product is 2n. And the sum of the second and second last terms is also 2n. In fact, every pair made of numbers equidistant from the ends (or the center) will add up to 2n.

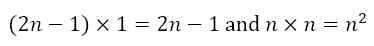

Let us consider the first pair from the ends. From (2n – 1)! we have 2n – 1 and 1 and from n2n – 1 we have n and n. Now, while the sum is the same for both pairs, the products are not the same.

In fact

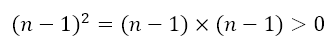

Now, from the previous post (and elsewhere, of course!) we know that the product of two positive numbers or two negative numbers is a positive number. Hence,

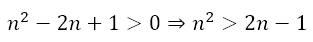

as long as n is not 1. We can expand the square to get

Generalization

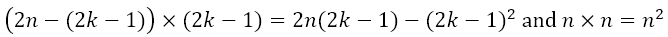

Now, if we chose a general pair (say, the kth pair), we would have 2n – (2k – 1) and (2k – 1) from (2n – 1)! and n and n from n2n – 1. Now if we take the products we get

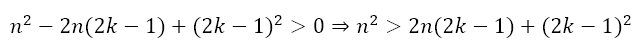

Once again, let us consider the product of two numbers as below

Expanding the square we get

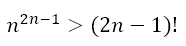

In other words, no matter which pair we pick, the product of the pair from n2n – 1, in which all terms are n, will be greater than the product of the pair from (2n – 1)! It follows, therefore that

Hence, we can conclude that 99! < 5099, that 101! < 51101, and that 199! < 100199.

Stepping Back

What we did in looking at the above was identify patterns between as many numbers involved in the question as possible. Here, specifically four things were crucial. First, both sides consisted of products of n numbers. Second, even though I did not explicitly mention it, the factorial contains all natural numbers from 1 to a particular higher number (n). However, on the other side we had n copies of the same number, the base. Third, the sum of numbers equidistant from the ends was a constant. And fourth, the base happened to be half this sum.

Recognizing these patterns allowed us to frame the issue in terms of the product of pairs of numbers whose sum is constant. From there it was an issue of recognizing that we can use something we knew about products, namely that the product of two numbers having the same sign is always positive, to produce the inequality that would allow us to proceed to a solution.

Now, it must be noted that not all solutions will involve identical steps. However, for most problems pattern recognition is crucial. Further, as I have shown here and here, mathematics is a coherent body of knowledge. This means that things we learn in one area can be reframed to be applicable in another area. Hence, in this post, something that a student might learn in a chapter on inequalities turns out to be applicable to algebra in general and number theory in particular.

The willingness to ‘borrow’ knowledge from another area of mathematics to make it applicable in a new area is something that we realize is important as mathematics becomes more complex. And speaking of that which is complex, I will be starting a new series on complex numbers next week. But next week’s post will only be a beginning. Till then, try proving that, for all n > 3, nn + 1 > (n + 1)n. If you need something to point the way, the series on e might be helpful.

Leave a reply to Primer to Complex Numbers – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply