A Promise Remembered

At the end of the previous post, I had announced that I will be starting a series on complex numbers. The name ‘complex numbers’ is unfortunate. Mathematics is already surrounded by an aura of mystery. There was no need to name something that would heighten that mystery and increase the trepidation of people – mostly teenagers – who are introduced to these numbers. In this series of posts, I wish to introduce you to the wonders and power and beauty of complex numbers. Along the way we will make some necessary pit stops that might seem irrelevant. But believe me, all of it will be beautifully relevant.

However, what I am going to cover in this post might be too trivial for some readers. If this is you, you might be wondering why I am beginning our journey here and with such ‘simple’ ideas. Well, it’s always best to start with a firm foundation rather than presume that everyone is on the same page. Hence, bear with me.

Our journey into the realm of complex numbers begins with a property of numbers that I highlighted two weeks back: The product of two positive or two negative numbers is always positive. “So what?” you may ask. “What’s the big deal?” you may wonder. “How is this relevant?” you may contend.

The Quadratic Equation

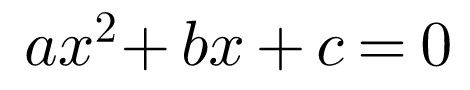

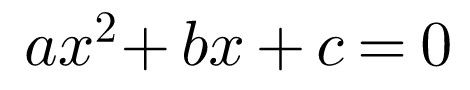

Let us begin our journey with the simple quadratic equation

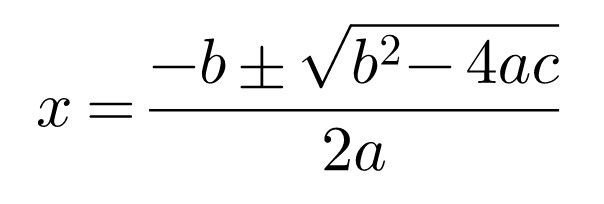

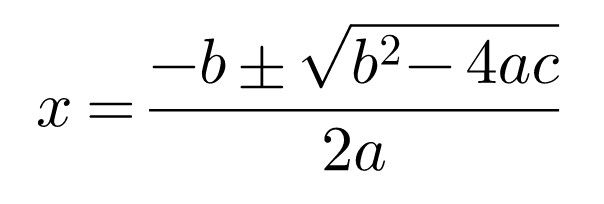

Students in grade 9 and higher may know that this equation can be solved by using the quadratic formula shown below.

But where does this formula come from? What kind of mathematical wizardry gives rise to it? I wish to devote much of the rest of this post simply to understanding how we get the quadratic formula. To this end, we start at a relatively innocuous result, the expansion of the product of two binomial expressions.

Product of Binomials

Since, I may have lost some of you, let me clarify some terms. In algebra, we encounter terms like ‘monomial’, ‘binomial’, and ‘polynomial’. These terms mean ‘one named’, ‘two named’, and ‘many named’ respectively. Expressions like a, m, and x, or even ab, ab2, and a3b5 are monomials because they have a single kind of term. Similarly, expressions like a + b, p + q, and x + y are binomials because they have two kinds of terms.

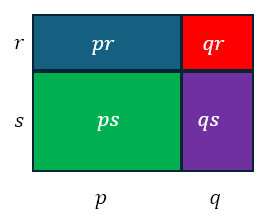

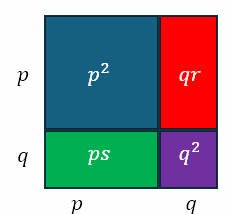

Now we can consider the product of p + q and r + s. We can visualize it as follows

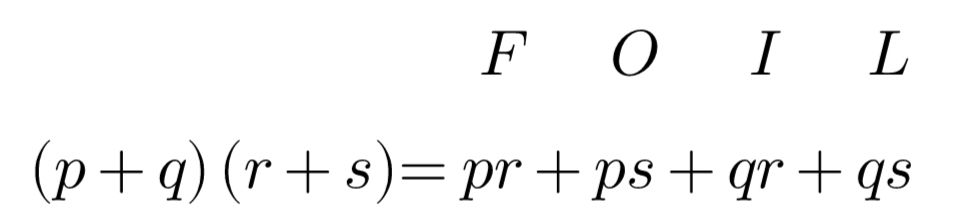

Algebraically, we can say that each term in the first binomial needs to be multiplied by each term in the second binomial. We can do this as follows.

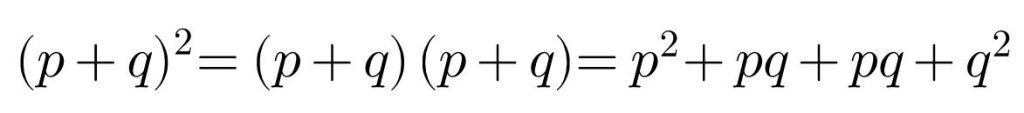

In the above, F represents the product of the first term in each binomial, O the product of the outer terms, I the product of the inner terms, and L the product of the last terms. We get the convenient acronym FOIL from this. When we use FOIL to the expansion of a perfect square, we get the following.

Perfect Square Expansion

When we use FOIL to the expansion of a perfect square, we get the following.

Students in grade 6 or 7 should be familiar with the above expansion. It is crucial to note that the perfect square expansion involves three terms. Hence only an expansion that includes all three terms can be considered a ‘completed square’. Unfortunately, as a high school teacher, I come across students ‘expanding’ the square as

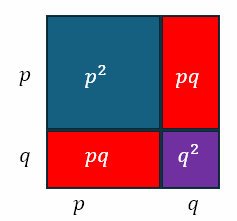

all too often, causing considerable grief and anxiety to me. We could, of course, visualize the expansion geometrically as follows:

The above figure shows that the expansion includes the two rectangles, each with area pq, which are excluded when a student ‘expands’ in the aforementioned way that causes me grief and anxiety.

Deriving the Quadratic Formula

Anyway, now we know the perfect square expansion, let us use that to solve the quadratic equation

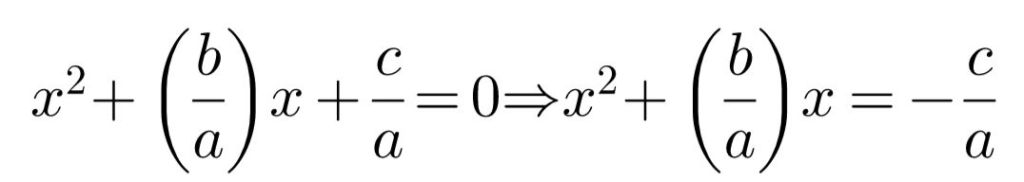

Let us first divide the whole equation by a and then move the constant term to the right. This will give us

Now we consider the two terms on the left to be the first two terms of the perfect square expansion. This gives us

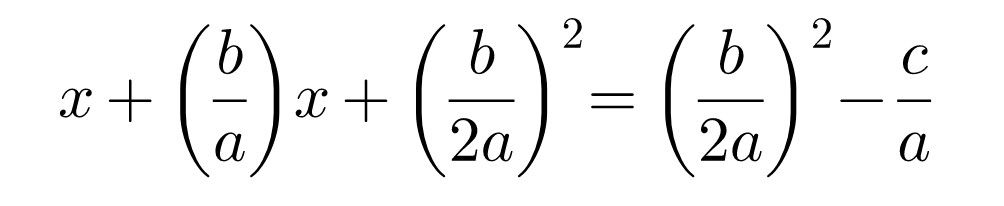

Now, in order to complete the square on the left, we need to add the third term. We need to do this on both sides so the equation has the same solutions. This gives us

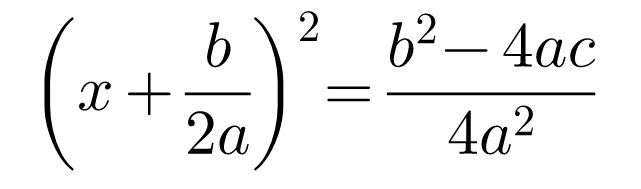

Now, the left is a perfect square. Hence, we can write the equation as

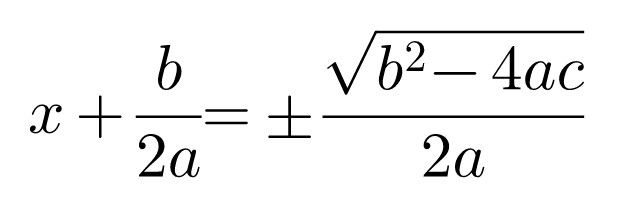

Now, we can take the square root on both sides to get

Now, moving the second term on the left to the right we get

The Promise of the Discriminant

Now, we observe that the quadratic formula just derived has a term under a square root symbol. This term is called the discriminant because it allows us to discriminate between the kind of solutions the equation will have. In particular, if Δ > 0 then we will have two distinct real solutions and if Δ = 0 then we will have one real solution. But what happens when Δ < 0? Till now we have only encountered non-zero numbers that are either positive or negative. And when we multiply two numbers with the same sign we always obtain a positive number. What sense can we make of a negative number under the radical sign? We will look at this in the next post. Stay tuned.

Leave a reply to A New Kind of Number? – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply