Brief Flashback

My mathematical world was thrown wide open when, in the ninth grade, my classmates and I were introduced to the study of trigonometry. Following that, when I studied at IIT – Bombay, I wrote a research paper titled The Synthesis of Coupler Curves and designed a mobile industrial robot, both projects requiring the use of trigonometry in the extreme. Hence, this post and the next couple are ones that I have actually been looking forward to.

Of course, this post forms a part of the ongoing series on complex numbers. However, this post forms the first in a pit stop that I had forewarned the readers about in the first post of the series. Yes, I said ‘first in a pit stop’. You see, unlike in an F-1 race, this pit stop will take some time!

The Theorem of Pythagoras

The journey into trigonometry begins with the ubiquitous theorem of Pythagoras or the Pythagorean theorem. This is not the place to debate where the theorem was first discovered or used or even if Pythagoras himself was an actual historical person or just a mythic figure concocted by the school that bore his name. Pythagoras’ theorem (as we call it in India) or the Pythagorean theorem (as people in North American tend to call it) states that, in a right angled triangle, the square of the length of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the lengths of the other two sides. Students are often instructed to memorize

However, without knowing what the symbols a, b, and c denote, the above equation is meaningless. In particular, without recognizing that c represents the length of the hypotenuse, the equation is not even valid! However, in my years of teaching students in high school, I have realized that many students are not even taught what the hypotenuse is!

An Unfortunate Realization

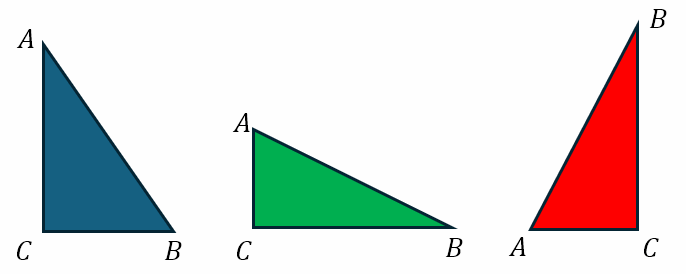

Most students are introduced to right angled triangles with figures like the ones below

In all three triangles, the side AB is the hypotenuse. However, the unfortunate fact is that in the above three figures AB is oblique (that is, neither vertical nor horizontal). And so many students have come to me after middle school with the understanding that the hypotenuse is the oblique side. So consider the figures below.

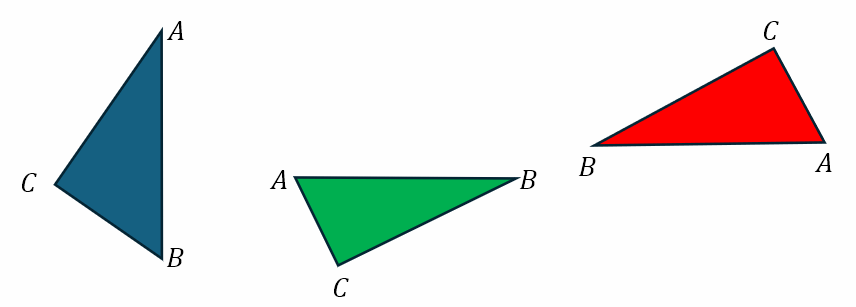

All I have done is rotate the earlier triangles. The hypotenuse should not change. In all three cases it is still side AB. However, now AB is either horizontal or vertical. And some students have understood that the hypotenuse is oblique. Hence, they conclude that the hypotenuse is AC or BC. The hypotenuse, however, is the side opposite to the right angle. This is something that teachers in the middle school need to ensure students understand. It is not the orientation of a side that makes it the hypotenuse but its relation to the right angle.

Pythagorean Triples

Anyway, returning to the equation for Pythagoras’ theorem, we have

I remember when I was introduced to this theorem back in my middle school days. My teacher introduced us to Pythagorean triples like (3, 4, 5), (5, 12, 13), etc. I remember spending a lot of time trying to find patterns to these triples. “Was there a way of finding new triples?” was the question I asked myself.

My search for patterns revealed that

That is, the square of the smallest number was the sum of the two larger numbers in the triple. Did this always hold true?

I discovered that

with (7, 24, 25) and (9, 40, 41) forming Pythagorean triples. Hence, it seemed that the pattern I had discovered did form Pythagorean triples. Could this be formalized in any way?

Formalizing the Sequence

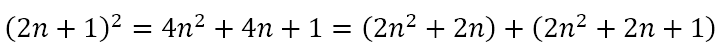

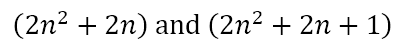

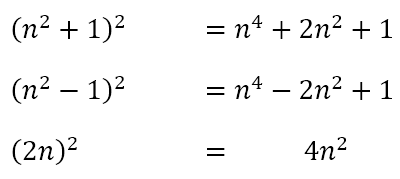

Later introduction to sequences and series allowed me to recognize that, in all the triples I was dealing with, the smallest number was an odd number. Moreover, the two larger numbers happened to differ by 1, the smaller being even. Knowing that 2n + 1 is always an odd number if n is a natural number, we can do the following

So, the square of the smallest number 2n + 1 can be split into

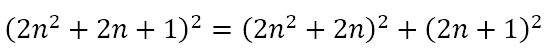

where the two numbers differ by 1 and the smaller is even. But do these three numbers satisfy Pythagoras’ theorem? Let’s check.

It is clear that

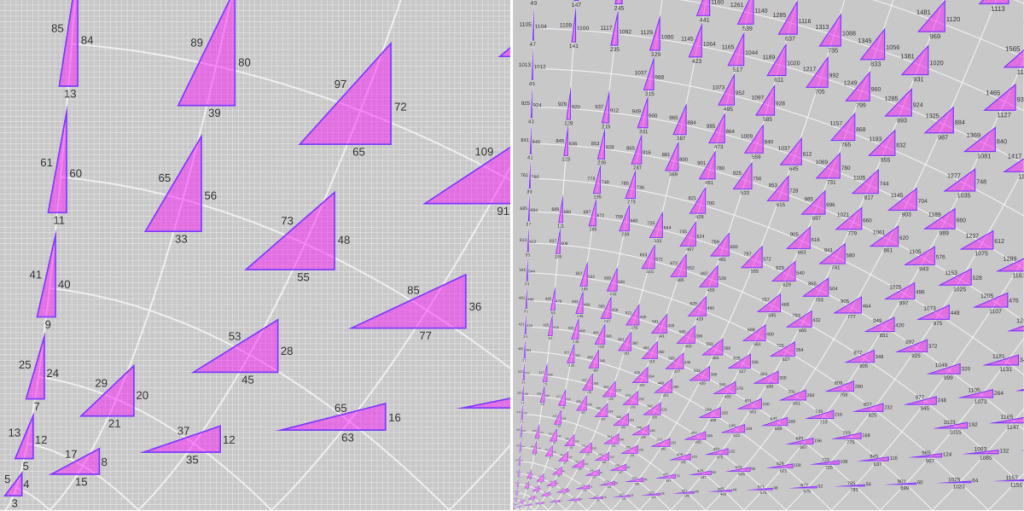

meaning that I had found a way to generate Pythagorean triples. Using this we can generate the triples (11, 60, 61), (13, 84, 85), (15, 112, 113), etc.

Another Sequence of Triples

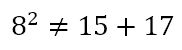

However, it was clear from the triple (8, 15, 17) that I had not found a way for generating all the Pythagorean triples. Indeed, this triple does not satisfy the original premise for the triples because

Was there a pattern that governed these three numbers? And could that pattern be extended, as before with the first pattern, to generate a new sequence of triples? Trying different patterns, I realized that the square of 8 was equal to twice the sum of 15 and 17. That is,

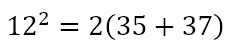

Was this something important? Using this pattern, I discovered that (12, 35, 37) was also a Pythagorean triple in which

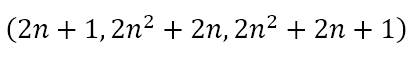

Could this be generalized? Like before, where 2n + 1 is an odd number, 2n will be an even number, which happened to be the case with the smallest numbers in each of the new triples. Further, the two larger numbers differ by 2 and are one less and one more than the square of half the smallest number. So let’s test this. If the smallest number is 2n, then the square of half of 2n would be n2 and the two larger numbers would be n2 – 1 and n2 + 1. When we test these three numbers we get

We can see that we have found a way of generating a new sequence of Pythagorean triples. Using this method, we can generate (16, 63, 65), (20, 99, 101), etc.

Yet Another Sequence

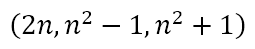

However, the presence of the triple (20, 21, 29) indicates that this second sequence of triples also does not exhaust all the possible Pythagorean triples. Despite this, I tried my hand at many such patterns, just to entertain myself. The first sequence consisted of triples having the form

The second sequence has the form

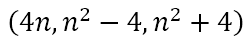

The third sequence is formed with the triples having the form

from which we can obtain (20, 21, 29), (28, 45, 53), and (36, 77, 85), etc.

Next Steps in the Journey

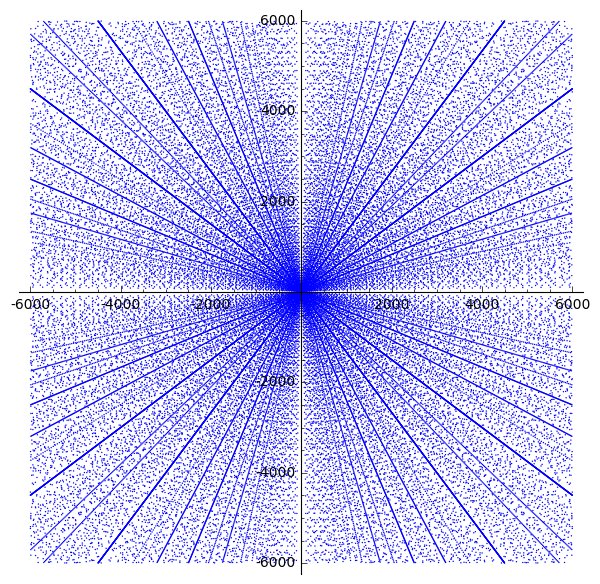

This was all recreational mathematics in the service of some higher understanding of how these triples, which have a geometric significance could relate to each other. There are, of course, other sequences of triples than the three we have uncovered. For example, the triples (33, 56, 65), (39, 80, 89) and (65, 72, 97) do not fit into the three sequences we have uncovered. I leave the reader to think of other possible ways of characterizing Pythagorean triples. And perhaps also think about the question, “While it is true that each sequence for generating Pythagorean triples generates infinitely many triples, is the number of such sequences also infinite? And can it be proved either way?”

Our journey into complex numbers required a pit stop at which we will learn some trigonometry. However, the journey is way too exciting, as we have hopefully seen in this post. The simple idea of trigonometry based on the right angled triangle, presented an opportunity to look into Pythagorean triples and some patterns with which an infinite number of triples can be generated. This, of course, is not strictly the study of trigonometry, but rather just my idiosyncratic diversion within this pit stop. Most of us know that trigonometry begins with defining ratios like sine, cosine, and tangent. Such strange names, especially the first two. Ever wonder how we got them? Keep your eyes glued for the next post.

Leave a reply to A Mathematical Partnership – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply