Looking Back, Looking Forward

In the previous post, we began our first pit stop during our journey into the wonderful realm of complex numbers. We looked at Pythagorean triples and some ways of generating sequences of triples. I admitted at the end of the post that this was not strictly a study of trigonometry and that we normally begin by defining the ratios since, cosine, and tangent. I promised you that I would tell you how we got these weird names. That is the agenda for this post. We will consider the ratios in the reverse order because the story of sine will take us on two globetrotting journeys that I am sure many, if not most, of you have never undertaken before this.

Triangle Nomenclature

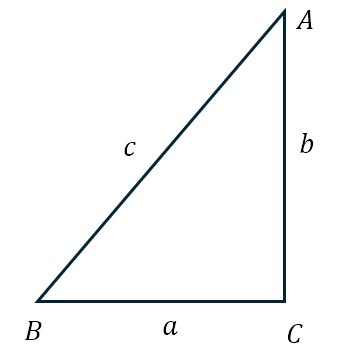

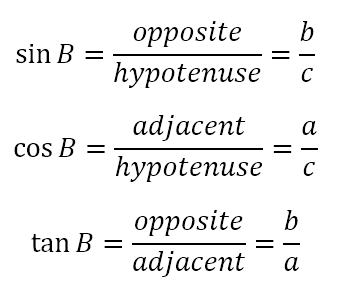

We begin our journey by considering some nomenclature. In what follows, I will assume that the triangle is ABC and that the right angle is at vertex C. Further, the length of the side opposite a given vertex will be denoted by the lower case letter of that vertex. Hence, the length of side BC, which is opposite vertex A, will be denoted as a. The figure below should clarify the nomenclature we will use in the discussions from now on.

Now the trigonometric ratios for angle B are defined as follows

How did we get these names?

Off on a Tangent

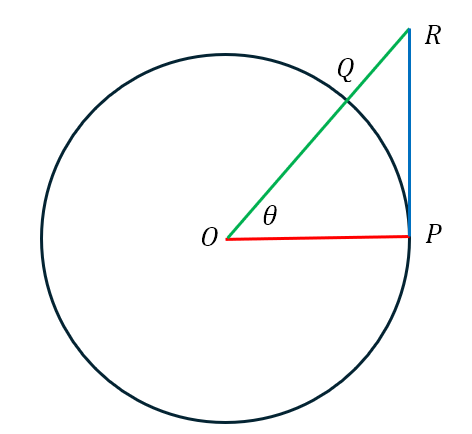

For the definition of the tangent, we begin with a unit circle. This is simply a circle with radius equal to 1 unit. Let us consider a unit circle with center at O. A point, P, is chosen on the circumference of the circle and a tangent is drawn at that point. From what we know about circles, this tangent is perpendicular to the radius OP. Now consider another point, Q, on the circumference of the circle, such that the angle made by the radius OQ with the radius OP is θ. Now we extend the radius OQ and the tangent at P so that they intersect at point R. All of this is shown in the figure below.

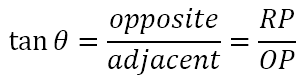

Now it is clear that ΔOPR is a right angled triangle with the right angle at vertex P. Now, with respect to the angle θ, RP is the opposite side while OP is the adjacent side. Hence, per the definition of the tangent above it should be clear that

However, OP = 1, since we are considering a unit circle, hence we obtain

However, RP is the length of the tangent corresponding to the points P and Q, the radii of which makes the angle θ. Hence, the name of the ratio. The tangent of an angle is the length of the tangent formed as above in a unit circle.

Cosplay Anyone?

Now, that’s all well and good. What about the cosine and sine? We go back to our original right angle triangle. However, now we focus on the vertex A. With respect to angle A, the trigonometric ratios will be as follows:

Note that

However, since C is a right angle, it follows that

In other words, A and B are complementary angles. When we say that

We are saying that the sine of an angle is the cosine of the complementary angle and vice versa. In other words, cosine is simply a shorthand for complementary sine, that is, sine of the complementary angle. But how in the world did the ‘sine’ get its name?

A Journey from Sanskrit to Latin

The ratio of the opposite side to the hypotenuse was used in many parts of the world. However, the name ‘sine’ strangely has its roots in the Indian subcontinent.

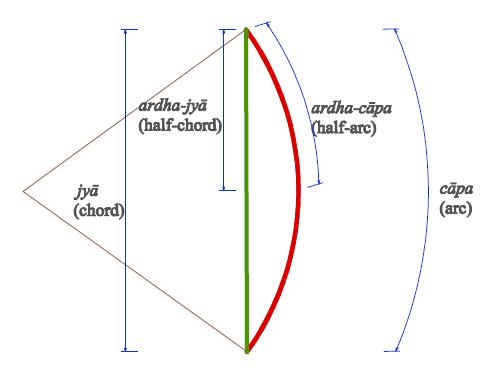

With reference to the figure above, the red arc and the green chord can be seen as a bow and string. Hence, Indian mathematicians named the string, that is, the chord, jyā, which is the Sanskrit word for ‘bowstring’. The half-chord was called ardha-jyā, which means ‘half bowstring’. Over time, the mathematicians realized that the ardha-jyā had more common use in the study of the triangles than did the jyā. Hence, they dropped the prefix and began calling the half-chord jyā.

From here we have two stories, equally fascinating, and equally plausible (or implausible).

One pathway indicates that a synonym for jyā in Sanskrit is jīvá. This term was adopted by Arabic scholars, who simply attempted to transliterate it into Arabic script as jība. However, since Arabic is not written with short vowels, this was rendered simply as jb. However, jība is not an Arabic word. In time, jb came to be pronounced as jayb, Arabic for “bosom”. When Latin scholars found these Arabic works, they were reluctant to use the word for “bosom” in a mathematical work. Instead, they chose the word ‘sinus’, the Latin word for the hanging fold of a toga over the breast, from which we get the final form ‘sine’.

The second pathway also observes the synonym jīvá but recognizes that jīvá also means ‘life’ in Sanskrit. From here the proposal is that the transformation happened earlier, when the word jīvá, now understood to mean ‘life’, was translated as ‘zind’, the Old Persian word for life. From there the name went westward to the Latin world where, unfortunately, the final ‘d’ of the name was misread as a breathing mark. This is understandable since, in Old Persian the letter for ‘d’ is 𐭣 and the breathing mark is 𐭥, making for a very small difference. Hence, the name got transliterated as ‘sine’, with the initial ‘z’ getting replaced with a ‘s’.

Both the above pathways are based on hypotheses concerning when the Sanskrit texts were translated into either Arabic or Old Persian. We do not possess any extant manuscripts that indicate which pathway was taken. It is also possible that both pathways were taken a few centuries apart from each other, leading to a strange convergence when the various corruptions and mistranslations reached the Latin world. However, both pathways indicate that the origin of our name ‘sine’ is from the Sanskrit word jīvá.

Knowledge Transcends Borders

People from the Indian subcontinent may express pride at the fact that the main trigonometric ratio (sine) obtains its name from a Sanskrit word and from the imagination of some native mathematician who saw a segment of a circle as a bow and string. While there is no denying this, the length corresponding to the ardha-jīvá was used in many places, from Egypt to Persia. In other words, the usefulness of the length of the half-chord in relation to the angle formed by the half-chord was recognized by mathematicians the world over. For me, the journey, regardless of the pathway we decide upon, indicates that the world has always been one in which knowledge moved across all artificial national borders. Beginning with a Sanskrit word jīvá we have ended with a Latinized word ‘sine’. And I can only hope that this permeability of knowledge continues despite all the obstacles that are being introduced.

Having seen how the trigonometric ratios received their names, we will continue our pit stop in the next post to understand how we decided to measure angles. Why do we have multiple units – the degree and the radian? Which one do I prefer? It will be pi day and I think the next post will be an appropriate one for the occasion. Stay tuned.

Leave a reply to Trigonometric Identity Crises – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply