A Triggered Review

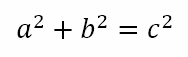

We have reached a remarkable junction in our journey through complex numbers. We are in the middle of a pit stop in which we are looking at some trigonometric ideas. And on the occasion of Pi day 2025, I think this post makes a lot of sense. Two weeks back, in My Trigger, No Metric, Beginnings, I introduced the idea of right angled triangles and Pythagorean triples. As a reminder, Pythagorean triples are sets of three integers that satisfy the Pythagorean theorem

In that post, I looked at different ways of generating these triples, an exercise with which I occupied myself shortly after I was introduced to these triples. Last week, in A Mathematical Partnership, we looked at how the common trigonometric ratios are defined. We also understood how the ratios – tangent, cosine, and sine – obtained their names.

It is time now to understand how we humans have decided to measure angles. After all, that is precisely what the trigonometric ratios deal with – the ratios of the lengths of sides of a triangle corresponding to the measure of the angle being considered.

A Degree of Definition

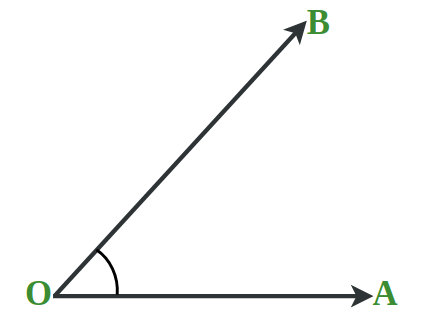

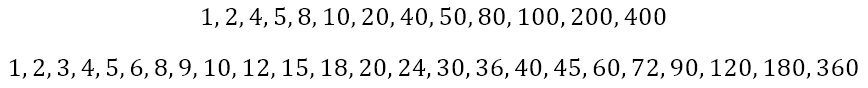

Most of us would have started our journey into angle measurement with the knowledge that a right angle is equal to 90 degrees, where the ‘degree’ is the unit of measuring angles. However, when I have asked students how to define a ‘degree’, many, if not most, of them are flummoxed. They know that 90 of these units give us a right angle. And some students may be able to then say that a degree is one-ninetieth part of a right angle. And while this is perfectly correct, the definitions are circular since the degree is defined in terms of the right angle and the right angle in terms of the degree. I could just as well define the angle below as a right angle and obtain a different measure of a degree than what we conventionally use.

You may object and tell me, “That angle is not a right angle.” But I could very well respond, “How do you know?” Indeed, since the definition of each term – right angle and degree – depended on the other, there is no way of deciding what each measure actually is.

Of course, there is a better way out. Unfortunately, none of my mathematics teachers told me this. And given the flummoxed expressions on the faces of most students when asked to define the degree or the right angle without reference to the other, it seems that this unfortunate practice continues to date.

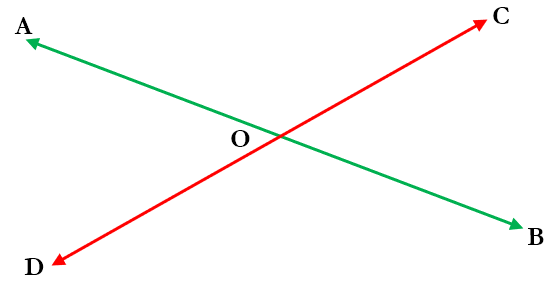

So let us begin with two intersecting straight lines as shown below

Now, apart from their location and orientation, there is nothing that differentiates the line AB from the line CD. Hence, the angle form by each of these lines at the point of intersection, O, must be identical. In other words, since ∠AOC + ∠BOC forms the straight line AB and, since ∠BOC + ∠BOD forms the straight line CD, the two measures should be equal. So we can write

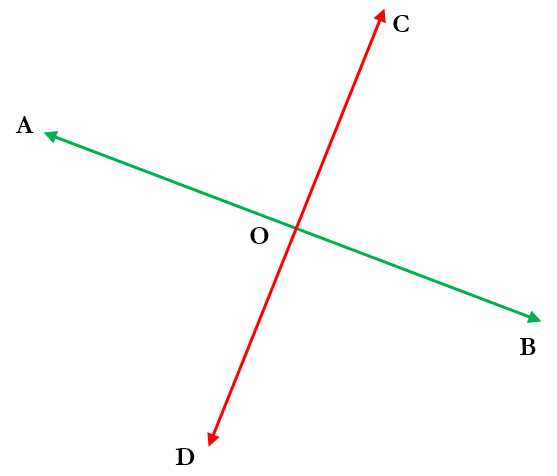

This is nothing other than saying that vertical angles (or vertically opposite angles) are equal. Now note that ∠BOC is adjacent to both ∠AOC and ∠BOD. These pairs of adjacent angles (∠AOC and ∠BOC or ∠BOC and ∠BOD) have the same angle sum, as we have stated above. However, there is only one configuration in which the adjacent angles will have equal measure. This is shown below

We can now define the four angles formed, all of which will have equal measure, to be right angles. From here, we can define the degree to be one-ninetieth part of the right angle and have no circularity in our definitions. But why do we define a right angle to be 90°? Why not a neat, nice round number like 100°? Of course, there is a unit of angle measure, the gradian, that is defined as one-hundredth part of a right angle. But I bet not too many people know about it. Why, when 100 is a part of the decimal system, being a power of 10, has this unit not caught on? And why do we function with the right angle being defined as 90°? The answer to this is two-pronged.

Celestial Constraints

We live on a strange planet, the only one we know of that can sustain the kind of life that we are accustomed to. Our planet revolves around an unimpressive, medium sized star in a orbit that takes it about 365.25 of its own rotations about its axis. That’s just a convoluted way of saying that one earth year is equal to approximately 365.25 earth days. The earth also has one natural satellite – the moon – which revolves around the earth in an orbit, which when viewed from earth, takes between 29 and 30 earth days to traverse.

The seasons are, for the most part, governed by the solar cycle of the earth. That is, the earth’s position relative to the sun has a greater impact on the seasons than does the moon’s position relative to the earth. However, it is difficult to determine exactly where in the solar cycle we are, since measuring exact times for sunrise and sunset is impractical almost everywhere. This means that determining the exact dates for the equinoxes, where the length of daytime and nighttime are equal, or the solstices, where the lengths of daytime and nighttime are extreme, is practically impossible.

Due to this, most human cultures have found it easier to mark the progress through the year ironically with the lunar cycles. After all, it is quite easy to look into the night sky and realize that the moon is not visible! Hence, most cultures have measures this progress through the year by starting months when the new moon cycle began.

However, as mentioned earlier, the moon takes 29 or 30 days to complete one cycle around the earth, as viewed from earth. This means that we encounter a new moon once every 29 or 30 days. Hence, most cultures have measured the progress through the year in terms of months that are 29 or 30 days long, following the lunar cycles. However, this results in a shortfall of about 11 days when compared with the solar cycle, resulting in a drift. To compensate for this, most cultures have the practice of adding an extra month every 2 or 3 years to get the calendar synchronized with the solar cycle.

So what we have is a solar cycle of approximately 365.25 days and a lunar cycle, twelve of which amount to between 353 and 355 days. The number 360, which is four times 90, falls neatly in this interval between the period of twelve lunar months and one year. The number 400, which is what we would get from the gradian, lies outside this interval and hence would not have been suitable for measuring anything on planet earth.

A Deliberation on Divisors

Of course, the second consideration, beyond what is forced upon us by the weirdness of the interaction between the sun, the earth, and the moon, is that we want a number that has a large number of divisors. This allows for dividing the year into many smaller fractions without having fractional days to account for. It is here that we see another advantage of 360 over 400. Here at their divisors

Apart from 1, which is a divisor of all numbers, and 400 and 360 respectively, since every number is automatically a divisor of itself, 400 has 11 divisors, while 360 has twice as many. In other words, 360 allows us to divide the year in 22 different ways without fractional days, while 400 only gives us 11 options.

Now, if we extricate ourselves from the realms of planetary rotations and revolutions and turn to geometry, we can see that dividing one complete rotation about a point into 360 parts gives us more options than dividing by 400 parts. On account of this and the link with the lunar and solar cycles, the degree was defined to be one-ninetieth part of the right angle.

However, we can see that it is an arbitrary division. Divisibility, which I discussed in Behind the Smoke and Mirrors, plays no role in determining the units of other quantities. Why should it play such a prominent role when it comes to measuring angles? In fact, let us look at how some fundamental units are defined.

Unimaginable Units

The second is defined as 9,192,631,770 cycles of radiation associated with the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the cesium-133 atom. If that number is strange, consider that the metre is defined as the distance traveled by light in a vacuum in 1/299,792,458 seconds. The kilogram is defined in an even more roundabout way by first defining Planck’s constant to be 6.62607015 × 10−34 joule second and then using the definitions of the second and the metre and the fact that one joule is equal to one kilogram times metre squared per second squared to arrive at the measure of the kilogram. What this lets us know is that, when it comes to units of measurement, divisibility is the least of our concerns.

What this means is that choosing a unit for angle measure based on divisibility is arbitrary. And since we understand that the twelve lunar cycles and one solar cycle are not sufficient grounds for measuring angles, any number we decide upon, whether 360 or 400, is going to be arbitrary at best. So, how do we decide on a better, more appropriate unit? We have seen earlier, in our series on e and π, that we are often forced to accept constants that are inconvenient. When I say inconvenient, I mean that we would never have thought to consider these numbers as significant. In fact, were these numbers not forced upon us, we would never in our wildest dreams have settled on anything even remotely close to their values.

So, how do we go about defining a unit for measuring angles? The previously mentioned units (second, metre, and kilogram) were all defined in terms of physical processes or quantities. We do not have anything like this for the angle since an angle is an idealized geometric entity. So, we are forced to consider other ways to define a new unit for angle measure.

Reining in Rotation

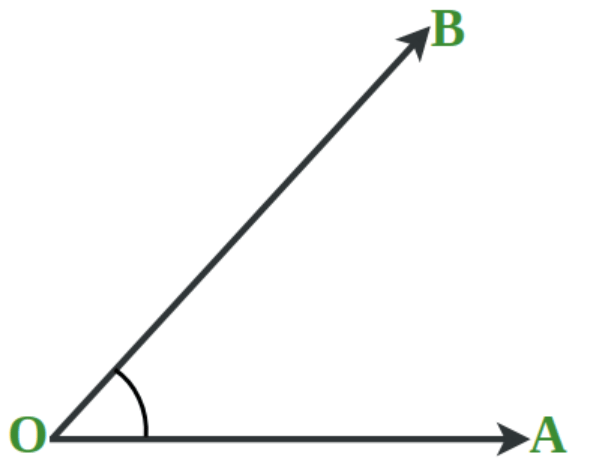

We start with the observation that an angle simply represents a rotation. So, for example, in the figure below, the angle AOB can be viewed as a rotation of OA in the counterclockwise direction with O being the center of rotation until A coincides with B.

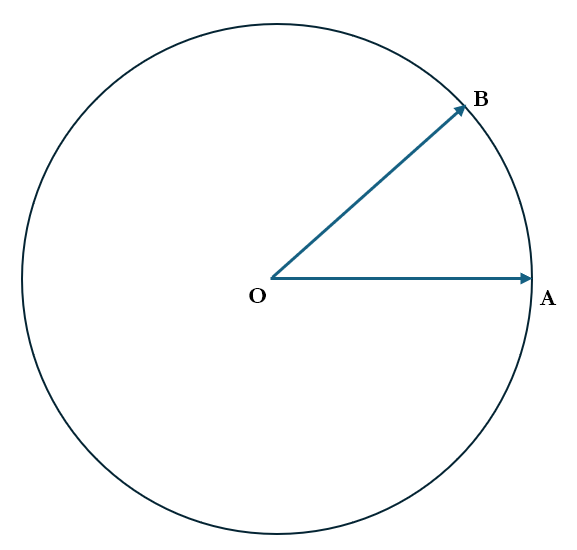

So the measure of the angle can be quantified as the amount by which we must rotate from the starting point until the angle is formed. We also recognize that a logical point would be one complete rotation about O, which would bring OA back to coincide with itself. Once we have done this, the point A would have traced the circumference of a circle with center at O and radius equal to the length OA as shown below

Now, we know that, if the radius of this circle is r, then the circumference is 2πr. We can also understand that, if point A traverses a distance that is twice the distance covered from A to B along the circumference, the angle by which OA would have rotated would be twice the original angle AOB. In other words, the distance covered is proportional to the angle through which OA rotates. We can also see that the distance is proportional to the radius. That is, if the radius is doubled, the distance covered would be double the original distance.

We now look at the formula

Since r represents the effect that the radius has on the circumference, we ask ourselves what the 2π represents. Remember that that distance covered during a rotation is proportional to both the radius and the angle of rotation. Since, r represents the proportionality to the radius, it must be the case that 2π represents the proportionality to the angle of rotation. However, the circumference itself represents a full rotation. Could it be then that 2π is the angle corresponding to the full rotation? What would that mean?

Now, while OA is rotating about O, point A traces arcs of the circle. Let the arc length corresponding to an angle θ be s. Since arc length is proportional to the angle of rotation, we can write

Now, if we keep the angle of rotation fixed at θ, then we can understand that, if the circle was twice as large, that is, if the circle had double the radius, then the arc length would be double what it was. Hence, the constant k must be none other than the radius r. This gives us

Realizing the Radian

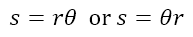

Comparing this with the equation C = 2πr we can see that, since C corresponds to the arc length for a full rotation, 2π does indeed correspond to the angle of rotation. Using the equation s = θr, we can see that, if we set θ = 1, we will get s = r. This gives us the definition of the new unit of angle measure, called the radian. The radian is the angle subtended by an arc of a circle that has length equal to the radius of the circle at the center of the circle. In other words, starting from OA, when we have rotated through an angle equal to 1 radian, the arc length involves would be equal to the radius of the circle. This is depicted below

With this definition of the radian, we can conclude the following

- One full rotation or the angle about a point is equal to 2π radians.

- A half rotation or the angle for a straight line is equal to π radians

- A quarter rotation or a right angle is equal to π/2 radians

From this we can also get the following conversion equation

The superscripted ‘c’ is the symbol for the radian, indicating ‘circular measure’ since the radian is the unit of angle measure defined solely based on the measurement of the circle. Of course, since the radian is the standard unit for angle measure, by convention it is often not indicated. Hence, in the equation

it is understood that the left hand side specifies π/3 radians.

Coming Full Circle

What we have seen in this post is that the degree measure is an arbitrary unit. It was adopted on account of two considerations – the orbital period of the earth (i.e. approximately 365.25 days) and the convenience introduced by the fact that 360 is a highly composite number with many distinct divisors. However, we saw that units for other quantities did not pay heed to any such requirements. This allowed us to think of the unit for rotations in terms of the features of the circle, leading us finally to the radian.

However, while almost all the other units have a certain degree (pun intended) of arbitrariness to them, the radian is completely defined in terms of the internal structure of the object it is designed to describe. For example, with the different measurement systems that humans have devised, we can imagine a world in which the standard unit of length is a cubit instead of a metre and the standard unit of mass is the pound instead of the kilogram. The second, based as it is on the period of rotation of the earth and the convenience of dividing successively by 24, 60, and 60, might have a slightly less amount of arbitrariness to it, at least for creatures who inhabit this planet. However, no matter where one may find oneself in the universe, all circles on Euclidean planes will yield the same measure for angles regardless of the name any extraterrestrial species may have given the quantity.

Having defined the radian, we will continue with our pit stop in the next post in which we will consider some trigonometric identities. Until then, hope you have seven turns for the better!

Leave a reply to Trigonometric Identity Crises – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply