The Seedbed of Mathematical Fecundity

Playing around with numbers is something that many, if not most, people who are fascinated with mathematics engage in. Most of the playing around does not lead to anything ‘productive’ in the sense that the results could find some practical application in real life. However, this does not stop people from just playing around with numbers. In a few cases, the playing around leads to some insights, as we saw in Arithmetic Doodling. In some cases, the insights seem so profound or intriguing that the person who reaches these insights decides to formalize it in a form of a conjecture.

In mathematics a conjecture is a statement that is offered without a proof. Since there is no proof, a conjecture is not taken as true. Conjectures are normally the result of uncountable hours of play with numbers. It is, in fact, impossible to start with a conjecture since one must have sufficient evidence to formulate a hypothesis, which would then require many more trials to test the hypothesis before a ‘dabbler’ or ‘doodler’ feels confident enough to propose a conjecture.

Once a conjecture is proposed it invites others to join in the play time by pooling their resources to proving or disproving the conjecture. Hence, conjectures have often been seedbeds for the development of other insights into mathematics and the properties of numbers. Indeed, if the conjecture is tantalizing enough, it can provide grounds for fruitful exploration of mathematics. Here, I wish to discuss two conjectures that have fascinated me for years.

The Goldbach Conjecture

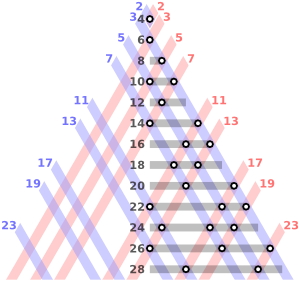

On 7 June 1742, Prussian mathematician Christian Goldbach wrote a letter to Leonard Euler. In this letter he proposed the following: “Every integer that can be written as the sum of two primes can also be written as the sum of as many primes (including unity) as one wishes, until all terms are units.” At that time, 1 was considered to be a prime number. However, in Cooking the Books I discussed why it is no longer considered to be prime. Goldbach’s initial proposition is quite puzzling. I means, every integer can be written as the sum of a series of ‘1’s! Of course, Goldbach himself recognized this and, later in the same letter, wrote, “It seems that every number that is greater than 2 is the sum of three primes.” Removing the idea that 1 is a prime number, we get the following, contemporary version of the conjecture: “Every even counting number greater than 2 is equal to the sum of two prime numbers.”

We can check these for some even numbers. For example, 4 = 2 + 2, 6 = 3 + 3, 8 = 3 +5, 10 = 3 + 7 = 5 + 5, 12 = 5 + 7, 14 = 3 + 11 = 7 + 7, and so on. As we consider larger even numbers, we are also reaching regions of the number line where the prime numbers are more sparse. Hence, it would seem that the conjecture could break down for sufficiently large even numbers. However, as of 2013, the conjecture has been shown to hold for prime numbers as large as 4×1017.

Why would this be important? What kind of use could the conjecture be put to if it could be proven? Today, most methods of encryption rely on large primes. For example, if I gave you the number 19939 and you knew that this was the product of two primes, then a short search would yield 127× 157 = 19939. If I gave you 2991119, you would take a bit longer to realize that 1549 × 1931 = 2991119. If we instead used two large even numbers, the key could be enhanced to involve appropriate factorization of the product and then selecting the larger prime of the Goldbach decomposition of the larger even factor and the smaller prime of the Goldbach decomposition of the smaller even factor (or the other way around), thereby increasing the complexity of the decryption.

The Collatz Conjecture

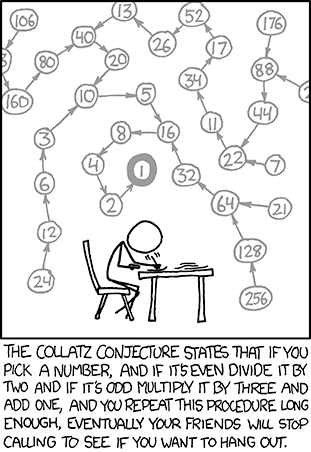

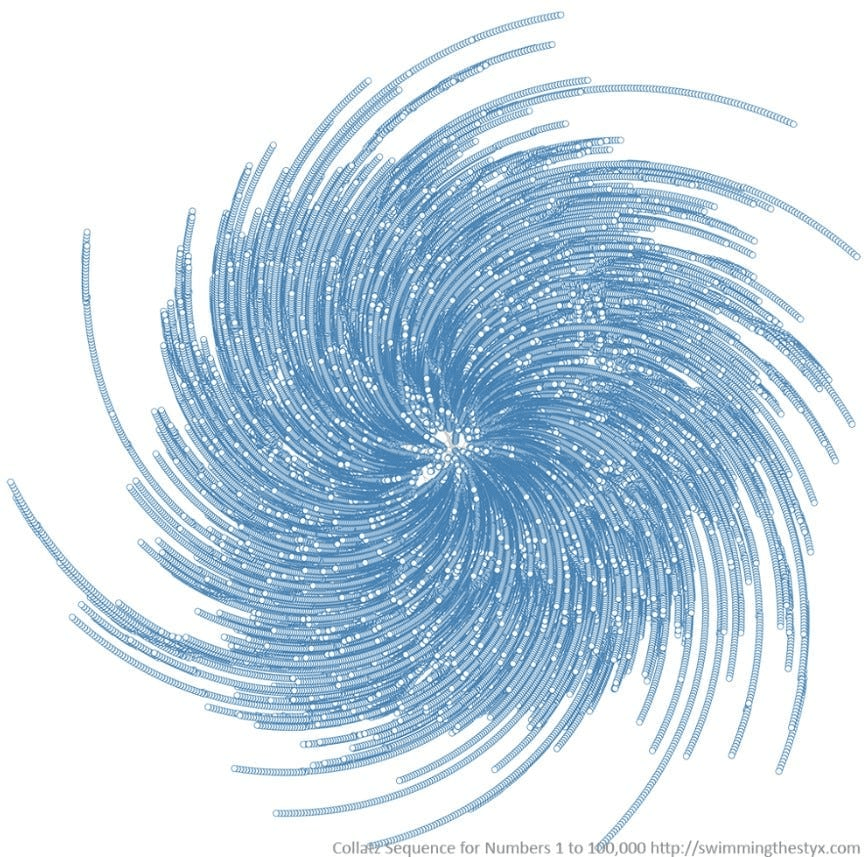

The second conjecture I wish to deal with was proposed by German mathematician Lothar Collatz in 1937. The conjecture involves a starting number and operations performed on the number to get the next number in the sequence. If the number is even, it is divided by 2. If the number is odd, it is multiplied by 3 and 1 added to the result. The question is: Does the sequence reach 1 no matter what the starting number is?

For example, starting with 15, we get 15, 46, 23, 70, 35, 106, 53, 160, 80, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1. Similarly, starting with 29, we get 29, 88, 44, 22, 11, 34, 17, 52, 26, 13, 40, 20, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1. And starting with108 we get 108, 54, 27, 82, 41, 124, 62, 31, 94, 47, 142, 71, 214, 107, 322, 161, 484, 242, 121, 364, 182, 91, 274, 137, 412, 206, 103, 310, 155, 466, 233, 700, 350, 175, 526, 263, 790, 395, 1186, 593, 1780, 890, 445, 1336, 668, 334, 167, 502, 251, 754, 377, 1132, 566, 283, 850, 425, 1276, 638, 319, 958, 479, 1438, 719, 2158, 1079, 3238, 1619, 4858, 2429, 7288, 3644, 1822, 911, 2734, 1367, 4102, 2051, 6154, 3077, 9232, 4616, 2308, 1154, 577, 1732, 866, 433, 1300, 650, 325, 976, 488, 244, 122, 61, 184, 92, 46, 23, 70, 35, 106, 53, 160, 80, 40, 20, 10, 5, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1

The Collatz conjecture has been shown to hold to 2.36×1021. However, as of today, no proof has been forthcoming. Indeed, no one has even suggested what its applications might be should the conjecture be proven at some stage. Despite this, the Collatz conjecture highlights the complex behavior of numbers that can be obtained using the simplest rules.

At its roots, the Collatz conjecture asks the question, “Can repeating the same sets of operations in an iterative manner always lead to the same result?” The fact that it is impossible to predict how many iterative steps it will take for a given starting number makes the Collatz conjecture particularly intractable.

An Invitation to Play

The two conjectures reveal how playing with numbers can yield deep insights. The Goldbach conjecture concerns the properties of numbers themselves. While it may have started in Goldbach’s mind as a simple though experiment, perhaps even a game, it has developed into something quite serious with possible applications in the protection of information. The Collatz conjecture concerns the properties of the basic operations on the numbers. It is still in the playful stage, with no real applications even being suggested. We can tweak the numbers to see if there are Collatz-like combinations of numbers and operations that share similar properties.

Both conjectures germinated in the ‘what ifs’ asked by the mathematicians to whom they owe their existence. Both are extremely simple to state. Both are quite straightforward to test for any given starting number. However, their simplicity belies the deep complexity at the heart of the conjectures.

Since conjectures are not theorems, they are not normally given the high place on a pedestal that theorems are given. However, once a theorem is proven, there normally isn’t much of a rush to find a different proof. There are, of course, some notable exceptions to this. However, conjectures, by their very nature, invite mathematical exploration. They present something that is still not settled and invite the dabbler or doodler to attempt to settle the matter one way or the other. I have briefly discussed just two such intriguing conjectures. I just hope I am alive when one of them is either proven or disproven.

Leave a comment