Defining a Circle

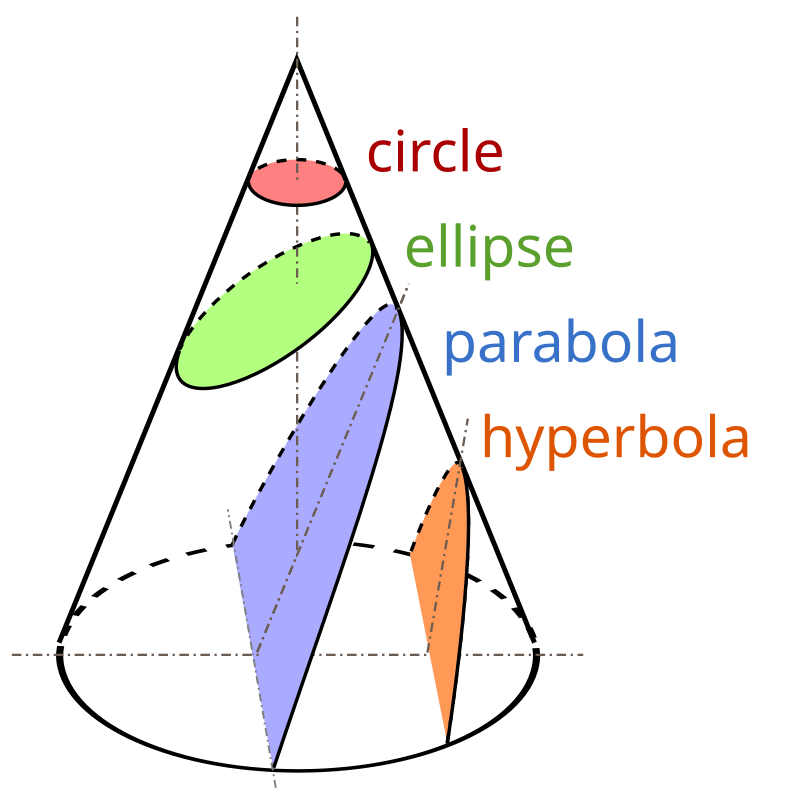

Three weeks back, I started a series on conic sections. I did not post the last two weeks due to being ill. We continue today with a study of the first conic section – the circle. Just as a reminder about conic sections, take a look at the figure below.

As is clear, a circle is the conic section obtained when a cone is cut by a plane that is at right angles to its axis. From the symmetry of the situation, it is clear that every point on the circle will be a fixed distance from the axis. Hence, when defining a circle in two-dimensions, we normally state, “A circle is the locus of a point that moves such that its distance from a fixed point is constant.” Here, the ‘locus of a point’ is the path traced by a point as it moves while satisfying one or more conditions. In this case, the condition is that the distance from a fixed point is constant. In particular, the fixed point is called the center of the circle while the constant distance is the radius.

The Equation of a Circle

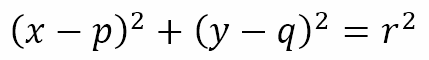

Suppose we have a circle with radius r and center at the point (p, q). If a point (x, y) lies on the circle, then by definition the distance of this point from the center must be r. This gives us

When we expand and rearrange, we will obtain

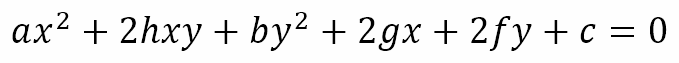

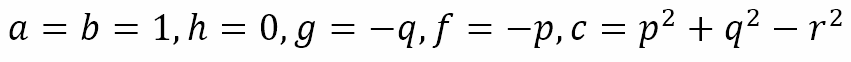

We can see that this is similar to the general second degree equation in two variables

with

Recall that, from the previous post, a general second degree equation in two variables describes a conic section. Since the equation we have obtained for the circle satisfies the conditions for such a general equation, our intuition that the circle is a conic section is validated.

We can also see that, if the center of the circle is at the origin, its equation will reduce to

Tangent at a Point

In our exploration of complex numbers, we determined that we can use polar coordinates to define the usual Cartesian coordinates. When we do this we get

Now, let us try to obtain the equation of the tangent to a circle at a point on the circle. Using Cartesian coordinates, we can say that a general point is (x1, y1) where

Now, it is known that the radius at a point on a circle is perpendicular to the tangent at that point. But how do we prove this? The traditional proof is by contradiction. Supposed we have a circle with center at O. Now let’s draw a tangent at the point A on the circle. Suppose radius OA is not perpendicular to the tangent. This means that there must be another point B on the tangent such that OB is perpendicular to the tangent. This means that triangle OAB is right angled at B. Hence, OA is the hypotenuse, meaning that OA > OB. However, since B is a point on the tangent other than the point of tangency (i.e. A), B must be further away from O than A is from O. This means that OB > OA. Since this leads to a contradiction, our assumption that the radius is not perpendicular to the tangent must be incorrect.

What would the equation of the tangent be at the point (x1, y1)? We will derive this in three different ways to show that the body of mathematical knowledge is internally consistent.

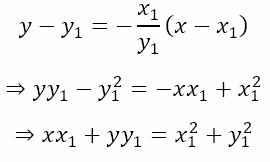

Derivation 1: Using Coordinate Geometry

Let us begin with the circle

The center is at the origin (0,0). Consider the point (x1, y1) on the circle. The radius will have a gradient (slope) equal to y1/x1. This means that the gradient (slope) of the tangent is –x1/y1. Hence, the equation of the tangent must be

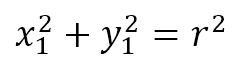

However, since the point (x1, y1) is on the circle, it follows that

Hence, the equation of the tangent becomes

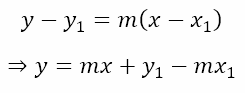

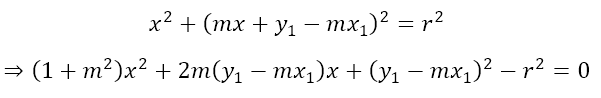

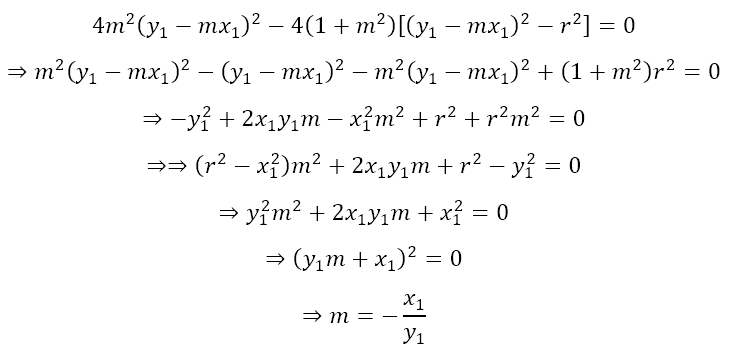

Derivation 2: Using Quadratic Equations

Now let us suppose a line through (x1, y1) with gradient (slope) of m is tangent to the circle. Then if we try to solve the equation of the line and the circle by eliminating y, we should obtain a quadratic equation in x. Now, the line through (x1, y1) with gradient (slope) of m is

Substituting this expression for y in the equation of the circle we get

Since the line is a tangent, this quadratic equation must have only one solution, meaning that its discriminant must be zero. Hence, we get

Since we have obtained the same value of the gradient (slope) as earlier, the rest of the solution proceeds as before and we will obtain the same equation for the tangent.

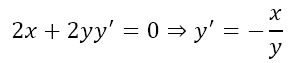

Derivation 3: Using Calculus

Now suppose we proceed by differentiating. In that case, we obtain

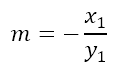

Now if we substitute the coordinates of the point of tangency, we will obtain

Again the gradient (slope) is the same as obtained earlier. Hence, we will obtain the same equation for the tangent.

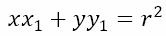

Equation of the Tangent

In all three cases, we obtained that the tangent at the point (x1, y1) to the circle x2 + y2 = r2 is

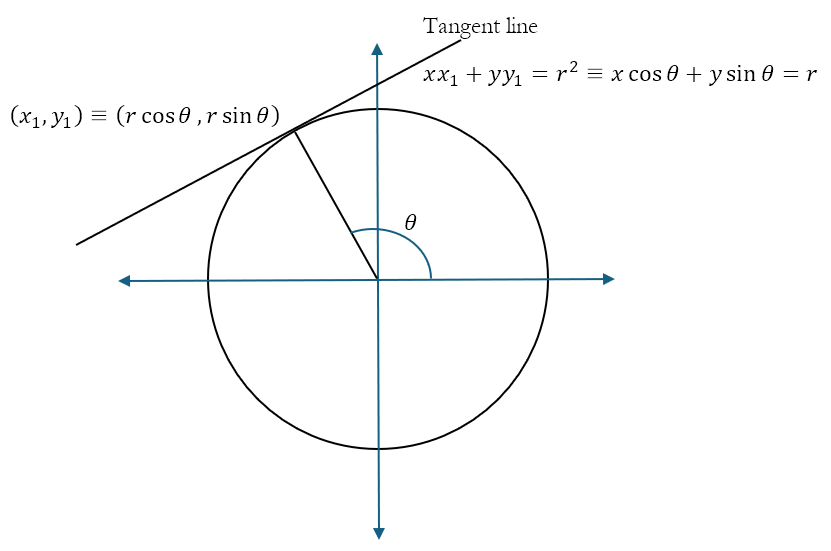

If we substitute the polar coordinates we will get

Here it is important to remember that θ is the angle made by the radius at the point (x1, y1) ≡ (r cos θ, r sin θ) and the positive x axis. This is depicted in the figure below

What this equation tells us is also the distance of the tangent from the origin, which happens to be r as expected. In other words, when expressed in polar form, the equation of any tangent to a given circle will lie at a fixed distance from the origin.

The Road Less Travelled

There is much more to student about the circle. However, I do not want this to simply be a regurgitation of things the readers were taught in school. Hence, in the next post, we will look at two not to common ideas related to curves in general and conic sections in particular. We will introduce them in the context of the circle, which is the conic section most of us are already familiar with. This will allow us to expand on these ideas when we deal with the other conic sections.

Leave a reply to Contacting Circular Polarity – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply