Starting the Parabolic Path

Those who know me well, know that I have two main areas of interest. Since you are reading this blog, you probably know or have surmised that mathematics is one of those areas. If you do not yet know, the other area is the exploration of my Christian faith and to fulfill that interest I blog at Purposes Crossed. If the title of this post seems strange, it is because I have intentionally combined the two areas. Obviously, this is a mathematics focused blog. Hence, the first word. For the second word, we need to understand that a parable is a pedagogical tool used widely by many teachers in the past, including Jesus.

But why do I add this word about parables? Well, a parable is a story in which there is one main point, one focal point, one could say. And as we turn to the second of the conic sections, the parabola, we realize that this geometric figure too has one focal point. Of course, we need to ask ourselves what a focal point would mean for a geometric figure. We will get to that later. However, before we begin our study of the parabola, it pays to realize that the Greek word for parable is parabolé (, which happens to be the word used by Euclid for the parabola. Hence, it is either a strange coincidence or an ongoing Greek joke that has lasted for two and a half millennia! Could it be that Euclid wanted us to see that the parabola is a conic section with a story? What could its story be? Or could it be that he wanted us to think of parables as strangely constructed word parabolas, whatever that could mean? Let us try to determine that.

Profligate Oddballs

We began the series on conic sections with a study of circles. There was much more we could have covered. However, I dealt with a few ideas that are not normally taught in high school curriculums around the world. As we turn from the circle to the other conic sections, namely the parabola, the ellipse, and the hyperbola, we need to introduce a new idea, the eccentricity of the conic section. We will see that the circle is simply a degenerate form of the ellipse. The previous two sentences should give you an idea of how mathematicians couch their jargon with tongue in cheek terms. I mean, we are talking about eccentric and degenerate geometric figures as though these inanimate squiggles on the page had personalities and moralities, as though they were oddballs and profligates! We will address the first of these terms, the eccentricity, shortly. The idea of the degeneracy of a conic section will have to wait till we discuss the ellipse.

The Eccentricity

All non-degenerate conic sections are defined by a point and a line. The point is said to be the focus and the line is called the directrix. For any general point on the conic section, the ratio of its distance from the focus to its distance from the directrix is a constant, which is called its eccentricity. The eccentricity of the parabola is 1. A conic section with eccentricity between 0 and 1 is an ellipse, with the circle having and eccentricity of 0. Finally, a conic section with eccentricity greater than 1 is a hyperbola. Let us proceed to derive the equation of a parabola in standard form.

The Equation of the Parabola

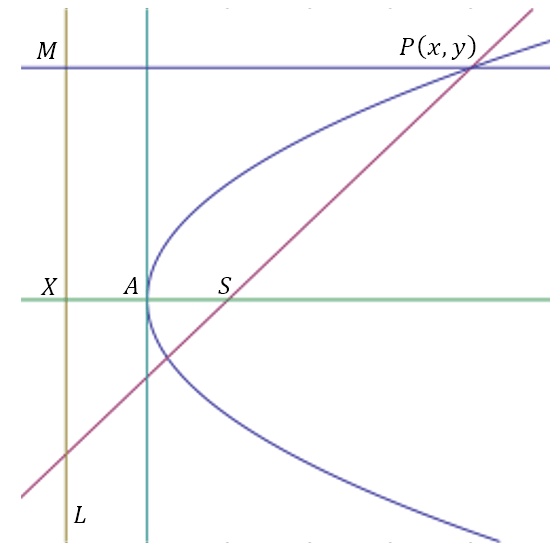

Consider a point, S, given to be the focus of a parabola and a line, L = 0, given to be the directrix of the parabola. Drop a perpendicular from S onto L and let the foot of the perpendicular be X. Let us define the distance SX to be 2a. Let A be the midpoint of SX. Then AS = AX = a, which by the definition of the parabola implies that A is on the parabola. Since A is the midpoint of the perpendicular from the focus to the directrix, A is said to be the vertex of the parabola. Let A be the origin of the coordinate system and let AS produced be the positive x axis. This is depicted below.

Then the coordinates of A are (0,0) and of S are (a,0). The coordinates of X will be (-a,0). Hence, the equation of L would be L = x + a = 0. Let P(x, y) be any point on the parabola. Let M be the foot of the perpendicular from P onto L. Then the coordinates of M are (-a, y). Then by definition of the parabola SP = PM. This gives us

Hence the equation of the parabola with axis along the x-axis, vertex at the origin, directrix formed by x + a = 0 and focus at (a, 0) is y2 = 4ax.

Now the latus rectum is the chord through the focus and perpendicular to the axis. Hence, the equation of the latus rectum is x = a. Substituting x = a in the equation of the parabola gives y = ±2a. Hence, the endpoints of the latus rectum are (a, 2a) and (a, -2a), giving that the length of the latus rectum is 4a.

The Riddle of the Parameter

When we dealt with the circle, we said that the coordinates of any point on the circle of radius r and centered at the origin would be (r cos θ, r sin θ), where θ is the angle formed by the radius joining the point to the origin and the positive x-axis. In this case, θ is said to be a ‘parameter’ and the aforementioned coordinates are said to be the parametric coordinates.

The parabola y2 = 4ax also can be described in terms of a parameter as follows. Suppose x = at2 and y = 2at. Since (2at)2 = 4a(at2 ), the point (at2,2at) lies on the parabola y2 = 4ax for all values of t, where t is a parameter. We will discover what the significance of t is shortly.

Equation of the Tangent

Before we get to that, let us obtain the equation of the tangent to the parabola at an arbitrary point (x1, y1) . Differentiating the equation y2 = 4ax we get

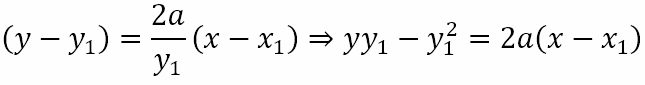

Hence, the slope of the tangent at (x1, y1) is 2a/y1. This means that the equation of the tangent will be

But (x1, y1) lies on the parabola. Hence,

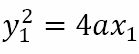

So, the equation of the tangent becomes

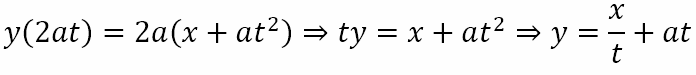

Substituting the parametric coordinates x1 = at2 and y1 = 2at, we get

Condition for Tangency

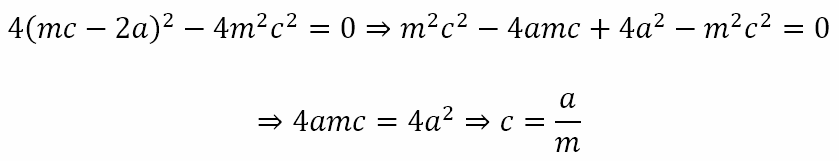

We can also obtain the equation of the tangent in terms of the slope of the line. Let the line y = mx + c be tangent to the parabola y2 = 4ax. Solving the two equations we get

Since the line is a tangent, the above quadratic equation should have a repeated root. Hence,

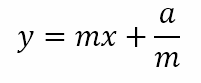

The last equation is the condition under which the line y = mx + c will be tangent to the parabola y2 = 4ax. In other words, replacing c with a/m we obtain that the line

is always a tangent to the parabola.

Answering the Riddle

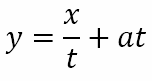

However, if we compare this with the parametric equation of the tangent

we can see that the two lines will be identical if t = 1/m. This tells us that the parameter t at a point on the parabola is nothing but the reciprocal of the slope of the tangent at that point. In other words, what seemed like a parameter introduced just to satisfy the equation of the parabola, actually turns out to have a deeper significance for the parabola itself. In other words, the parameter itself describes an essential property of the parabola. Or to put it in words with which I began this post, the parameter tells a story about the parabola. It is a parabolic way of describing the parabola.

In the next post we will look at some more properties of the parabola, including the chord of contact and the polar. If you have forgotten what those words mean, please refer to Contacting Circular Polarity. Till then, stay focused! And remain profligate oddballs!

Leave a reply to Contacting Parabolic Polarity – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply