Brief Recapitulation

In the previous post, titled Mathematical Parables, I introduced us to the parabola. Just to jog your memory, a conic section is a a geometric figure such that, for any point on the conic section, the ratio of its distance from a fixed point, called the focus, to its distance from a fixed line, called the directrix, is a constant, known as its eccentricity. A parabola is a conic section which has an eccentricity equal to 1.

In the previous post, we derived the equation y2 = 4ax as that of the parabola in standard form, obtained the parametric coordinates (at2,2at) for a general point on the parabola, derived the equation yy1 = 2a(x + x1) of the tangent at a point (x1, y1) on the parabola, and the condition c = a/m under which the line y = mx + c is a tangent to the parabola. In this post, we will deal with the chord of contact and the polar of a point with respect to the parabola.

Chord of Contact

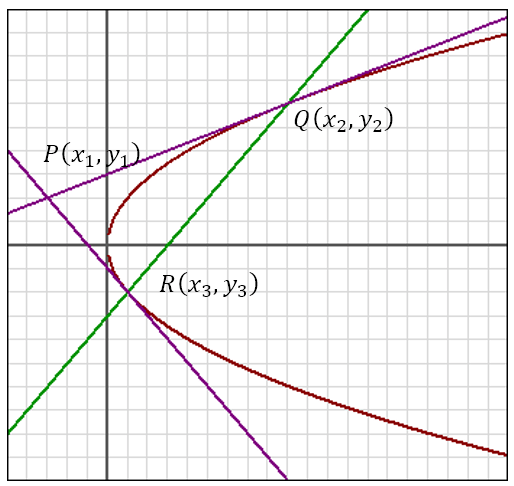

Let P(x1, y1) be a point outside the parabola y2 = 4ax. From point P tangents are drawn to touch the parabola at Q(x2, y2) and R(x3, y3). This is shown in the figure below.

Since PQ is the tangent at Q, its equation must be yy2 = 2a(x + x2). Since P lies on this tangent, its coordinates must satisfy this equation. Hence, y1y2 = 2a(x1 +x2)

Since PR is the tangent at R, its equation must be yy3 = 2a(x + x3). Since P lies on this tangent, its coordinates must satisfy this equation. Hence, y1y3 = 2a(x1 + x3)

It follows then that Q(x2, y2) and R(x3, y3 ) satisfy the equation yy1 = 2a(x + x1) and since two points determine a straight line, the equation of the chord of contact QR must be yy1 = 2a(x + x1).

Pole and Polar

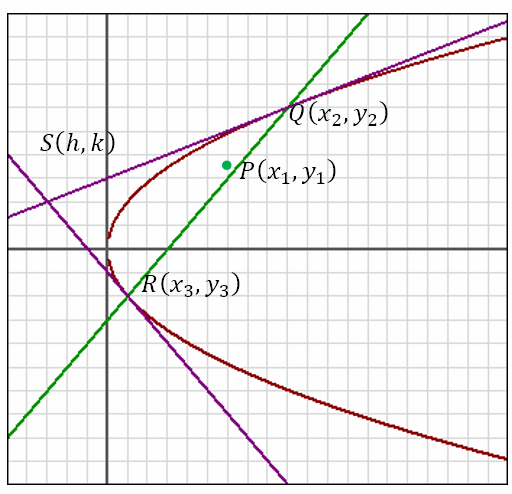

Having derived the equation of the chord of contact of the point (x1, y1) with respect to the parabola y2 = 4ax let us derive an equation for the polar of the same point with respect to the parabola. Let P(x1, y1) be a fixed point placed anywhere relative to the parabola y2 = 4ax. A line through P is free to pivot about P. In general, this line will cut the parabola at two points. Suppose these points are Q(x2, y2) and R(x3, y3). Tangents are drawn to the parabola at the points Q and R. Let these tangents intersect at S(h, k).This is shown in the figure below.

It is clear that at the line pivots about P, the points of intersection, Q and R, of the line with the parabola will vary. This means that the tangents at Q and R will vary. Hence, the point S where the two tangents intersect will move. The locus (fanciful name for ‘path’) of S is known as the polar of P with respect to the parabola and P is known as the pole of the polar with respect to the parabola. It can be seen from the diagram that QR is the chord of contact of S wrt the parabola. Hence, its equation should be yk = 2a(x + h). However, P lies on QR. Hence, y1k = 2a(x1 + h). Generalizing, we obtain the locus of S to be yy1 = 2a(x + x1).

Tangent, Chord of Contact, and Polar

Once again, as in the case with the circle, we can reach the observation that the same equation represents the tangent at the point (x1, y1), the chord of contact of the point (x1, y1), and the polar of the point (x1, y1) with respect to the parabola y2 = 4ax. In this case, the equation is yy1 = 2a(x + x1). Once again, it is the context within which the equation is used that tells us what the equation represents.

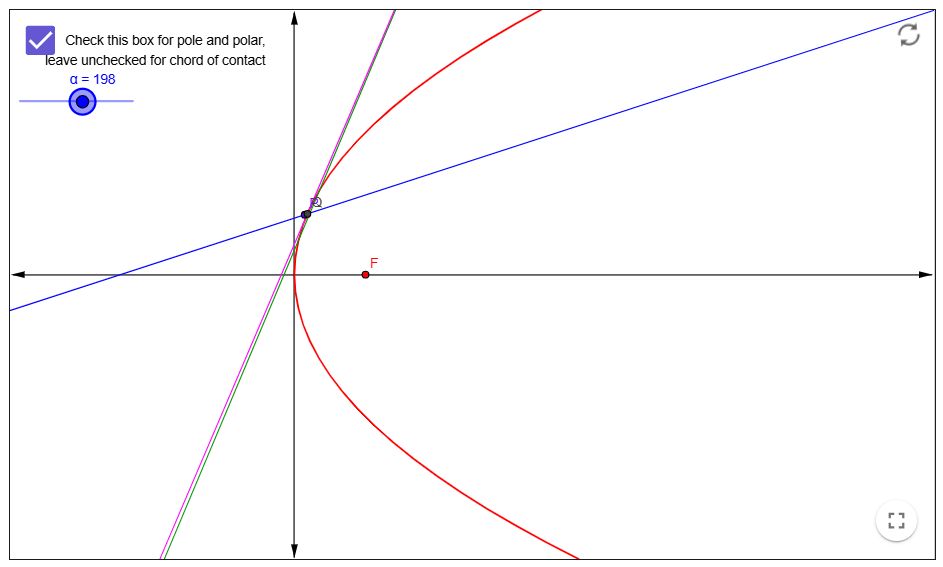

If you wish to see how the chord of contact, pole and polar relate to a parabola, you can click here for a Geogebra App that I created. With the checkbox on the top left unchecked, you can see how the chord of contact varies. Just click on the point P and drag it around! If you check the checkbox on the top left, you can explore how the pole and polar vary. Again, just click on the point P and drag it around to position the pole. Then move the slider for α to change the orientation of the line through P. This will change the positions of Q and R and, therefore, the bright pink tangents at those two points. The point of intersection of these two tangents will move, tracing the green line, which is the polar.

Once again, from the applet you will notice that the chord of contact technically only represents the part of the line that is inside the parabola which the polar represents the part that is outside the parabola. And when P is on the parabola, the chord of contact degenerates to the point P, meaning that the tangent itself is the polar. This is why all three features of the parabola, as in the case of all the conic sections, share the same equation.

A Bone Picked

In the post Contacting Circular Polarity I had expressed my dismay that concepts such as chord of contact and pole and polar are not taught in most (any?) contemporary curriculums. However, just the past week, I came across a post on LinkedIn in which the author was lamenting the return to archaic topics like analytical geometry in India’s mathematical education. I wanted to refer to that post here. However, the Amazon delivery guy came when I was reading the post on my phone and when I returned to LinkedIn I was unable to locate the post. The author claimed that a number of mathematics teachers or professors had voiced their disapproval of this return to such archaic concepts. The author argued that we should instead be focusing on AI and Data Science. Given that I have embarked on this series on analytical geometry, I had to address the issue raised by the post. If any reader can locate the post, please share it with me.

As mentioned in earlier posts, analytical geometry helps us link geometry, which can be quite abstract, to algebra, which is less so. This allows us to obtain a geometric interpretation of algebraic equations and an algebraic interpretation of geometric phenomena, both of which help link disparate sides of mathematical knowledge. While algebra is very left brain focused, geometry is more right brain focused. This gives the student an ability to visualize arcane algebraic equations from a geometric perspective and to rationalize geometric insights from an algebraic perspective. Hence, those who seem to think that analytical geometry is archaic have failed to appreciate what this branch of mathematics brings to the table.

However, in very few other fields do we find a rejection of the archaic. Physics students learn about Newton’s corpuscular theory of light and the ether theory of light even though both have been conclusively disproven. Chemistry students still study Dalton’s and Thomson’s atomic models even though they are now demonstrably wrong. I have mentioned four theories, each proven to be incorrect, that science students still learn to this day. And people complain about analytical geometry not because it is wrong (it is not) but because it is archaic? I wonder how many English teachers would say that English students should not study Shakespeare or Blake, Dickenson or Brontë because they are archaic and we have contemporary poets to study!

Since I am unable to locate the post, it may be that I have misrepresented the views of the author. In that case, I will be willing to apologize. Not for the stance I take concerning analytical geometry, but for misrepresenting him/her. My stance on analytical geometry remains unwavering. It is an essential part of mathematical education and probably the only relatively easy part of mathematics that is able to bridge the gap between the two hemispheres of the brain. I hope that, through this series on conic sections, I am able to communicate just this.

Leave a comment