Setting the Stage

I have long been fascinated by patterns that exist in numerical sequences. Early exploration led me to the discovery of the Fibonacci series and the associated Golden Ratio. I also came across Pascal’s Triangle, which remains a source of intrigue. Hence, when I was introduced to the tests for divisibility, I devoured them with a voraciousness unmatched till then in my life. By some accounts, I stumbled upon the tests for divisibility by 3 and 9 all by myself, without the direct involvement of my teachers.

And when my teachers ‘failed’ – or so it seemed to my young mind – to give me a test for divisibility by 7, I attempted to derive one such test. Of course, I failed at the task. Try as I might, I could come away with no universal test that would hold true for a number having any number of digits. What was it about 7?

You see, we have tests for divisibility by 2 (number ends with 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8), 3 (sum of digits is divisible by 3), 4 (last 2 digits are divisible by 4), 5 (number ends in 0 or 5), 6 (number satisfies conditions for 2 and 3), 8 (last 3 digits are divisible by 8), 9 (sum of digits is divisible by 9), 10 (number ends with 0), 11 (difference of the sums of alternate digits is divisible by 11), and 12 (number satisfies conditions for 3 and 4). Why was 7 so stubborn?

Moreover, why did these tests work out the way they did? Perhaps if we uncovered the reasons for which the tests for 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, etc. are what they are, we can gain some insight into why 7 refuses to submit to our efforts.

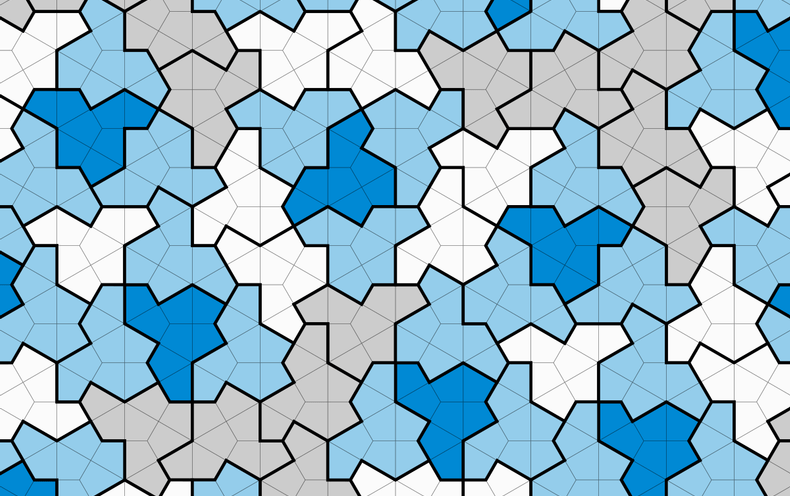

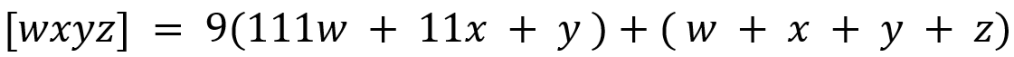

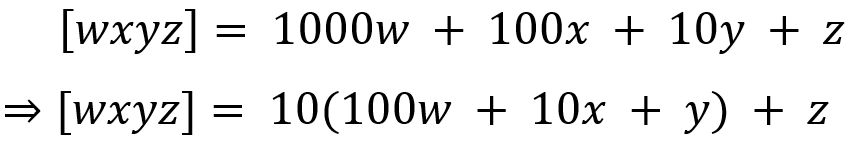

In what follows, I will use the notation [wxyz] to denote a 4 digit number which has w in the thousands position, x in the hundreds position, y in the tens position, and z in the units position. Hence, the value of the number

Divisibility by 2

Naturally, the first test of divisibility is that by 2. In order to derive this test, we do the following:

Here it is clear that the sum of the first three terms is divisible by 2. Hence, the number [wxyz] as a whole will be divisible by 2 if and only if z is divisible by 2, which happens when z = 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8, giving the test for divisibility by 2.

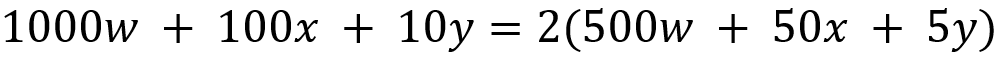

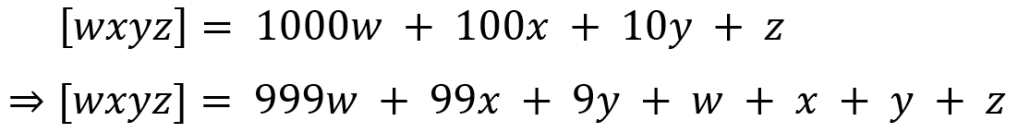

Divisibility by 3

When we reach divisibility by 3, we can do the following:

That is

Here it is clear that the first term is divisible by 3 and 9. Hence, the number [wxyz] as a whole would be divisible by 3 or 9 if the second term, that is the sum of the digits, is divisible by 3 or 9 respectively. This gives rise to the tests for 3 and 9.

Divisibility by 4

For the test for divisibility by 4, we manipulate our number as follows:

Here it is clear that the first term is divisible by 4. Hence the number [wxyz] as a whole will be divisible if the second term, which is the number [yz] formed by the last two digits, is divisible by 4. This yields the test for 4.

Divisibility by 5

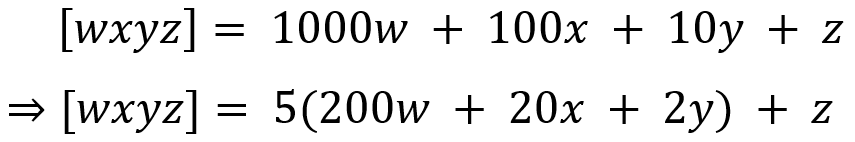

The test for divisibility by 5 is easy to remember. But it is obtained by doing the following:

Here it is clear that the first term is divisible by 5. Hence, the number [wxyz] as a whole will be divisible by 5 if z is divisible by 5, which happens when z is either 0 or 5, giving us the test for 5.

Divisibility by 6 and 12

Since 6 is the product of 2 and 3, a number that satisfies the condition for 2 and 3 will be divisible by 6. Similarly, since 12 is the product of 3 and 4, a number that satisfies the condition for 3 and 4 will be divisible by 12.

Divisibility by 8

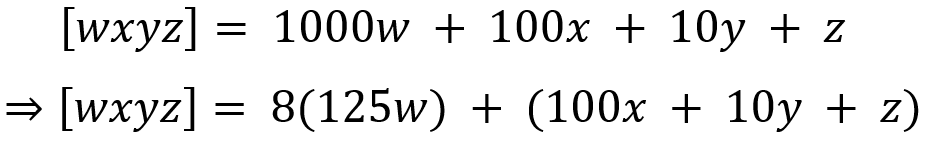

The test for divisibility by 8 is an extension of that derived for 4. We proceed as follows:

Here it is clear that the first term is divisible by 8. Hence, the number [wxyz] as a whole will be divisible by 8 if the second term, which is the number formed by the last three digits, is divisible by 8. Hence, we get the test for 8.

Divisibility by 10

The test for divisibility by 10 follows the same logic as that for 5. In order to derive it we do the following:

Here it is clear that the first term is divisible by 10. Hence, the number [wxyz] as a whole will be divisible by 10 if z is divisible by 10, which happens when z is0, giving us the test for 10.

Divisibility by 11

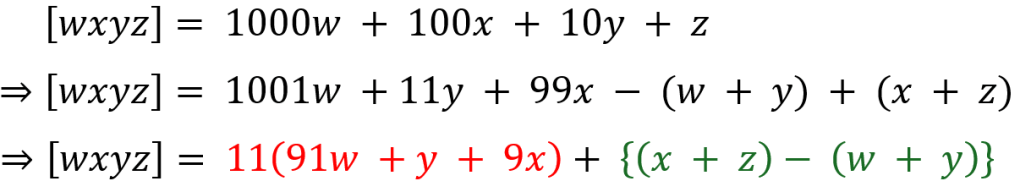

When we come to divisibility by 11, we realize that it is not as straightforward as the ones that came before. Indeed, while the test for divisibility by 11 was taught when I was in school, it has mostly been removed from the mathematics curriculum today. Nevertheless, the test for divisibility by 11 is quite instructive. So let us see what we can learn from it. Given the number [wxyz],, we can do the following:

Here it is clear that the term in red is divisible by 11. Hence, the number [wxyz] will be divisible by 11 if the term in green, which is the difference or the sum of alternate digits, is divisible by 11, yielding the test for 11.

Divisibility by 7

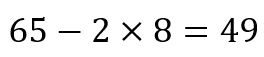

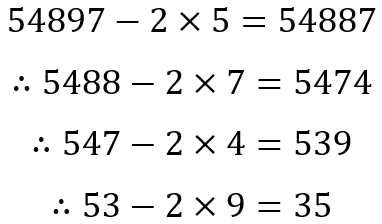

When we come to the number 7, there is indeed a test for divisibility by 7. It goes as follows. Suppose we have the number […xyz]. Then if […xy] – 2z is divisible by 7, the original number is divisible by 7.

For example, consider the number 658. We can proceed as follows:

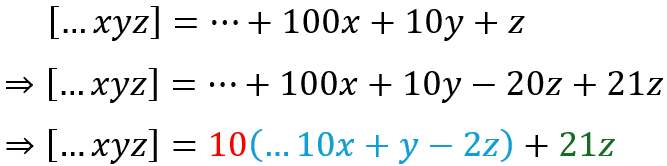

Since 49 is divisible by 7, it follows that 658 is divisible by 7. But how does this work? Consider the number […xyz]. We can proceed as follows:

Here the term in green is obviously divisible by 7. The term in blue is the one we are asked to test for divisibility by 7. If it is divisible by 7, then the whole number is divisible by 7. But what if we had a much larger number? How would we proceed? Suppose, for example, that we were testing for 548975. We would have to proceed as follows:

Since 35 is divisible by 7, we can conclude that 548975 is divisible by 7. This is a recursive method that is fool proof. It is also easy to remember. However, due to the recursion and the fact that most of us probably barely remember multiples of 7 that are 3 or more digits long, for a number with n digits, we will have to perform n – 2 recursions before reaching a 2 digit number that we could recognize as a multiple of 7 or not.

Each recursion involves a multiplication and a subtraction. This results in 2n – 4 operations for the n – 2 recursions.

Attempt at Divisibility by 7

We can see that in most of the tests, we generate 2 terms, the first of which is automatically divisible by the number under consideration. Then the test devolves into testing if the second term is divisible by that number. For the tests for 3 and 9 we saw that one less than a power of 10 is automatically divisible by 3 and 9. For the tests for 4 and 8 we saw that multiples of 100 and 1000 are automatically divisible by 4 and 8 respectively.

Even for the test for 7 we followed the same basic idea indicated by the 21z term. However, while the other tests yielded the answer in a single step, the test for divisibility by 7 involved a recursive approach. Hence, for a 6 digit number, we had to perform 4 recursions to obtain a 2 digit number for which divisibility by 7 can be placed in memory.

The test for 11 was most illuminating. We saw that some powers of 10 (i.e. 10 and 1000) are 1 less than a multiple of 11 while other powers of 10 (i.e. 1 and 100) are 1 more than a multiple of 11. Could we use a similar approach to obtain another test for divisibility by 7?

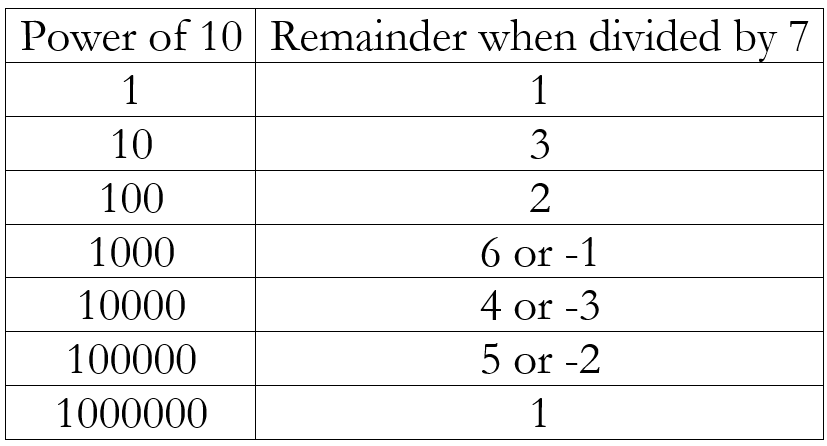

To attempt that, let us see how we fare when we divide powers of 10 by 7. The table below shows the remainders.

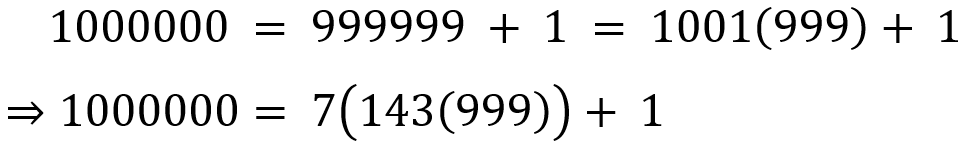

After the 6th power of 10, that is 1,000,000, the patterns repeats. And this is because

Hence, when we have a number of the form [xyzxyz] it is necessarily divisible by 7. Since 1,000,000 is 1 more than a number that follows this pattern (i.e. 999999) the pattern of remainders will repeat after every 6th power of 10.

Now we observe that the first three powers of 10 give remainders of 1, 3, and 2 respectively. The next three powers of 10 give negative remainders in the same order.

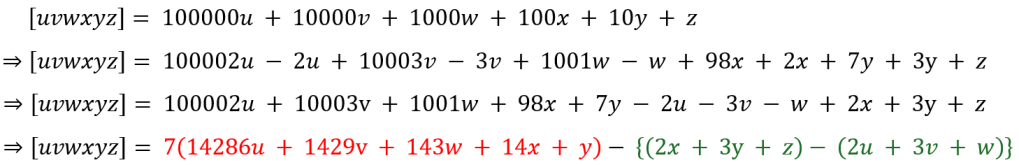

So if I had the number [uvwxyz], we can rewrite it as

Here the term in red is obviously divisible by 7. Hence, the whole number [uvwxyz] is divisible by 7 if the term in green is divisible by 7. Let’s put this to the test and let’s label the term in braces as D.

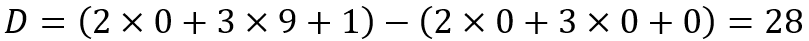

Consider a 2 digit number (say 42). Here, u = v = w = x = 0, y = 4 and z = 2.

Since 14 is divisible by 7, 42 is divisible by 7.

Consider 91. Here

Since 28 is divisible by 7, 91 is divisible by 7.

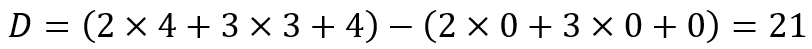

Consider a 3 digit number (say 434). Here, u = v = w = 0, x = 4, y = 3 and z = 4.

Since 21 is divisible by 7, 434 is divisible by 7.

Consider a 4 digit number (say 2072). Here, u = v = 0, w = 2, x = 0, y = 7 and z = 2.

Since 21 is divisible by 7, 2072 is divisible by 7.

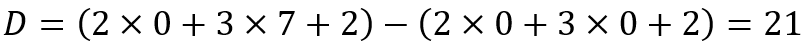

Consider a 5 digit number (say 24962). Here, u = 0, v = 2, w = 4, x = 9, y = 6 and z = 2.

Since 28 is divisible by 7, 24962 is divisible by 7.

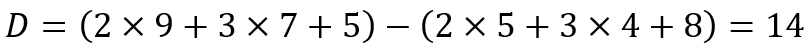

Consider a 6 digit number (say 548975). Here, u = 5, v = 4, w = 8, x = 9, y = 7 and z = 5.

Since 14 is divisible by 7, 548975 is divisible by 7.

Now I grant that this process is not intuitive. There is no identifiable uniformity that would allow it to function as a test that is easy and quick to use as the other tests. There is, of course, a pattern. In each block of 3 digits, the digits are multiplied by 1, 3, and 2, respectively going from right to left. Alternate blocks are to be added and once all that is done, the difference between the sum of alternate blocks is to be evaluated. The resulting number, which will, in all likelihood, be a 2-digit number, is tested for divisibility by 7 and the result here tells us about the divisibility by 7 of the original number.

If we counted the number of operations involved, we will see that each of the parentheses in the green term above, involves 4 operations. For a number that has 3m digits, we will have m groups with m – 1 operations linking the groups, yielding 5m – 1 operations in all. With the previous test, a number of similar length (i.e. 3m), would require 6m – 4 operations. It is clear, then, that the second test will be quicker than the first. However, the first test is more straightforward than the second.

Stepping Back

However, despite the fact that the second test is not intuitive, such a process reveals the logic behind the other tests. Those tests are quite easy to implement, allowing us to take for granted their efficacy. And if my memory serves me right, none of my teachers ever really explained to me why those tests work, as I have done above. Hence, these algorithms come across to many students as some kind of mathematical wizardry, where reliable results are obtained by some numerical sleight of hand. Actually, I have a nagging feeling that many mathematics teachers themselves have no idea why the tests for 3, 4, 6, 8, and 9 work and most probably have no clue about the test for 11.

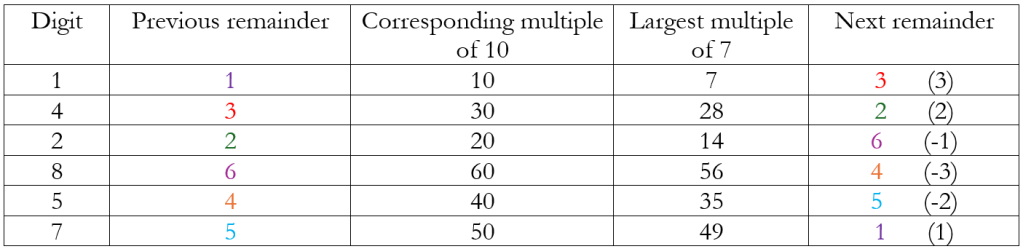

If we take a step back to understand what happened when we derived this test for divisibility by 7 we can see that, when we divided powers of 10 by 7, we obtained 6 different remainders. We took powers of 10 because that is precisely what the place value system of writing numbers shows us as we have seen when we expanded [uvwxyz] and other numbers. Concerning the remainders, we can further observe that in fact we obtain all the possible remainders we can get when we divide by 7. This is actually revealed in the recurring pattern ‘142857’ when we divide any integer that is not a multiple of 7 by 7. The increasing powers of 10 only shift this pattern rightward to give us the remainders as follows

Here the numbers with the same color indicate how the pattern is generated, that is, how one remainder morphs into the next as division is continued. Note especially the numbers in parentheses in the last column and compare them with the numbers in the second column of the previous table.

Since the recurring pattern for division by 7 is a string of 6 numbers (142857), we get 6 different remainders, which, in the case for 7, are all the remainders we could obtain. Due to this our test involved 6 different numbers u, v, w, x, y, and z. Since the pattern of remainders 1, 3, 2, -1, -3, -2 conveniently formed 2 blocks of 3 numbers, we were able to reduce the test to a replicating pattern involving the sum of 3 numbers for which the difference is finally taken.

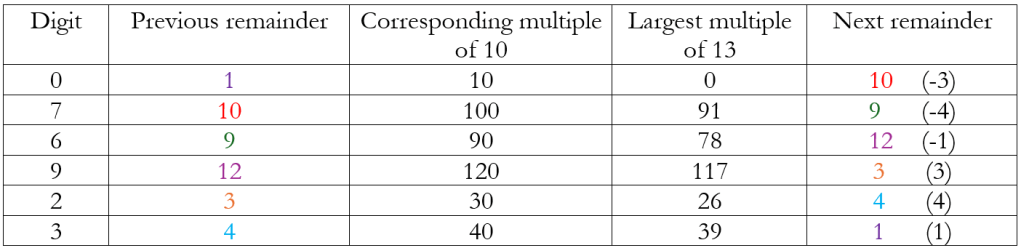

Now, when we obtain tests for divisibility, we need focus only on the prime numbers as seen in the very brief descriptions for divisibility by 6 and 12. Powers of 2 present a unique situation as seen in the tests for 2, 4, and 8. However, if we focus on the prime numbers, the next one we encounter is 13. What would a test for divisibility by 13 look like? It pays to note that the recurring pattern for division by 13 is ‘076923’ and then to generate the following table:

Now it helps to not rush to any conclusions. While division by 7 and 13 produced patterns of length 6, this is not the case for all primes, as we should expect. For example, division by 17, the next prime, produces the full complement of 16 possible remainders. Anyway, getting back to 13, I encourage the reader to use the table above and the ones before it to obtain a test for divisibility by 13. Also do attempt a test similar to the recursive first one. Please do put your findings in the comments. And I will see you next week.

Leave a reply to Round and Round – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply