Definitionally Limited

Almost everyone who has studied beyond Grade 4 has probably heard of the mathematical constant π. Students are told that π represents the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter. That is all well and good. But how do we calculate it? I mean, we could potentially use a piece of string to measure both the circumference and the diameter. Even assuming no error in determining one exact rotation around the circle (for the circumference) and diametrically opposite points (for the diameter), the experiment is limited by the measuring instruments.

Suppose, however, we have access to measuring instruments (necessarily hypothetical) that can measure to the accuracy of the Planck length (i.e. 1.616255)×10-35 m), we will still only get measurements with about 40 significant figures. Since the accuracy of a mathematical calculation cannot exceed the accuracy of the least accurate number in the calculation, we will get a result that has 40 significant figures for π. Actually, if we look at any measuring instrument, we will see that there are hardly any that give more than 4 significant figures. This means that even obtaining 3.1416 as a 5 digit approximation for π is a pipedream if we take the measurement.

However, we are told quite early on that π is an irrational number. This means that, when we attempt to write π in a decimal format, the expression continues endlessly without any pattern of repetition. What this means is that the definition of π cannot be used to determine its value! In fact, we should have known this precisely from the definition. If C÷D is irrational, at least one of the numbers, C and D, must be irrational. Otherwise, C÷D will give us a rational number. So we can see that the definition of π that is based on measurement is an impractical way of obtaining the value of an irrational number like π.

Now, if you refer back to our posts on e, especially the opening post, you will realize that this is exactly the opposite issue we faced there. The definition of e was able to give us results to as great an accuracy as we desire. While we had to do quite a bit of heavy mathematics before we obtained a usable infinite series, once we had obtained the desired infinite series, we could use it to obtain the value of e to any arbitrary level of accuracy.

Not so with π since its definition in terms of measured lengths renders it limited precisely because no measuring instrument can be indefinitely accurate.

Why the Symbol

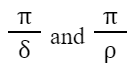

Before we proceed, however, it is interesting to make a brief detour concerning the history of how the Greek letter π came to be used to denote this ratio. The earliest known use of the π in a similar context was to designate the semiperimeter of the circle. With the Greek letters δ and ρ representing the diameter and radius of the circle, the many mathematicians used the ratios

to denote what we currently would denote as π and 2π respectively.

In his 1727 paper An Essay Explaining the Properties of Air, Euler used π to denote the ratio of the circumference to the radius. Just 9 years later, in 1736 in his book Mechanica, Euler used π to denote the ratio of the circumference to the diameter. From then on he consistently used the latter designation and, because he corresponded prodigiously with other mathematicians, his notation eventually was adopted though, even till 1761 there was quite a bit of fluidity.

Despite the confusing history of the symbol, something utterly lacking in the case of e, π has been the more popular number and more efforts have been made to calculate its digits than the digits of e. Obviously, this means that mathematicians have some other result, necessarily stemming from the definition of π, that allow the generation of different infinite series that can be used to calculate the value of π. The current record stands at 105 trillion digits, which required 75 days of dedicated computer time by a computer company. But if the definition ofπ is limited, how in the world do mathematicians calculate its digits?

The Polygon Method

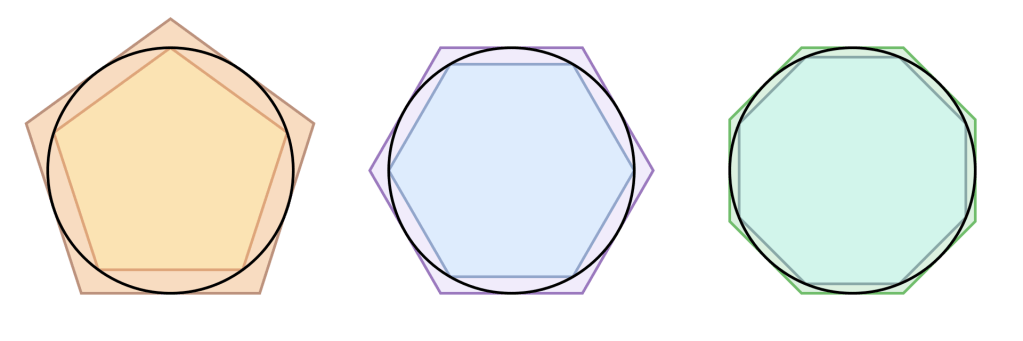

The original impetus came from the study of polygons, specifically regular polygons. In the figure below we see the same circle repeatedly inscribed and circumscribed by regular polygons. On the left we have pentagons. In the middle are hexagons. And on the right are octagons.

Here it is possible to define the circle as having a radius of 1 unit. Then the distance of the vertices of the inscribed polygon to the center of the circle will also be 1 unit. And the perpendicular distance of the center of the circle from the sides of the circumscribed polygon will also be 1 unit. Using this, the perimeter of both polygons can be determined. Also we can easily see that the circumference of the circle has a value between the perimeters of the two polygons. This allows us to place lower and upper bounds on the value of π. With polygons having more sides our accuracy becomes better and we can get tighter bounds.

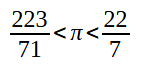

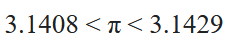

Using this method with 96-sided regular polygons, Archimedes, in the 3rd century BCE, obtained that

This gives us

which most students in middle school will realize are accurate only to 3 significant figures! 96 sides and 3 significant figures! I don’t know about you, but I think this is a really poor payoff. I applaud Archimedes for sticking with his 96-sided polygons.

Not to be outdone by the redoubtable Archimedes, Liu Hui from the Wie Kingdom used a 3,072-sided polygon and determined that the value of π was 3.1416. That’s a factor of 32 more sides yielding just 2 more digits!

Not having any other methods at the time, around 480 CE and using Liu Hui’s algorithm with a 12,288-sided polygon, Zu Chongzhi showed that π could be approximated by 355÷113, which gives 3.1415929…, accurate to 6 digits. In 499 CE, Aryabhatta used the value 3.1416, though, unfortunately, he does not tell us the method he used or if he was using someone else’s value.

Mathematicians continues using this polygon method for the next few centuries. In 1424 CE Jamshīd al-Kāshī determined 9 sexagesimal digits of π, the equivalent of about 16 decimal digits, using a polygon with 3×228 sides! Finally, Christoph Grienberger obtained 38 digits in 1630 CE using a polygon with 1040 sides!

I do not wish to detract from the achievements of any of these great mathematicians. The patience and perseverance they displayed is exemplary. Morover, they achieved what they did in an age before calculators and computers. They only had their hands and minds to work with. Despite their achievements – or rather precisely because of them – it is evident that the polygon method is wonderfully accurate, but also woefully inefficient.

The Path Forward

Apart from the slowness with which the polygon method converges to the value of π, it is evident that, when you have a finite number of terms, here represented by the finite number of sides of the polygon, regardless of how large the number of sides may be, the final result will only be achieved as a value between two bounds specified by the inscribed and circumscribed polygons. Due to this, mathematicians have devised what can only be described honestly as ‘workarounds’, methods that yield the value of π but not because of some direct application of the definition.

These methods fall into two large branches. First, we have the methods that rely on some kind of iterative formula. Second, we have methods that yield an infinite series. We must ask ourselves how an iterative formula or infinite series can be generated for a number that is defined in terms of the ratio of two lengths. In the next two posts we will see just how this is done.

Leave a comment