A Slice of the Pi

We are in the middle of a study of π. In the previous post, A Piece of the Pi, we introduced π. We saw how its definition itself, based on measurement, is inadequate for calculating the value of π to a great accuracy. We then saw how mathematicians circumvented this problem by using inscribed and circumscribed regular polygons to obtain lower and upper bounds for the value of π. We saw that that endeavor culminated with the efforts of Christoph Grienberger, who obtained 38 digits in 1630 CE using a polygon with 1040 sides! We realized that this method, while mathematically sound, converges too slowly to be of any long term practical use.

At the end of the post, I stated that there were two broad approaches to address this issue, one using iterative methods and the other using infinite series. We will deal with the infinite series approach here and keep the iterative method for later.

Snail’s Pace To Infinity

Since π is a constant related to the circle, it should come as no surprise that the most common infinite series are derived using the circular functions, a.k.a. the trigonometric functions. Specifically, since 2π is the measure of the angle around a point in radians, the inverse trigonometric functions, which map real numbers to angles are used.

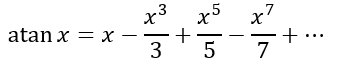

Now we haven’t yet dealt with deriving infinite series using calculus in this blog. I assure you I will get to that soon. For now, I ask you to take my word with what follows. Using what is known as the Taylor series, we can obtain

which is known as the Gregory-Leibniz series after James Gregory and Gottfried Leibniz, who independently derived it in 1671 and 1673 respectively.

Using the Gregory-Leibniz series and knowing that arctan 1 is π÷4 we can substitute x = 1 to obtain

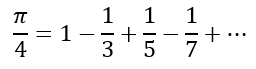

We can take increasingly more terms of this series to see how it converses. Doing so gives us the following

We can see that this series also converges quite slowly. Even after n = 10000, we only have π accurate to 2 decimal places! Unfortunately, even though I have a Wolfram Alpha subscription, the computational engine timed out for values greater than 10000. So that’s the maximum I was able to generate. But it should be clear that this series produces values that are no better than the ones generated using the regular polygons.

Machin-like Formulas

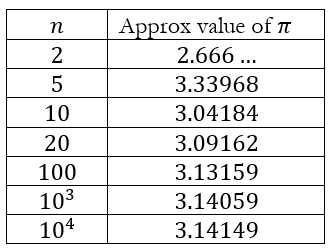

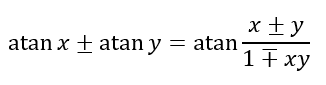

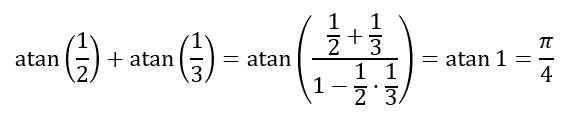

However, mathematicians are quite creative. Using the formulas

it is not too difficult to obtain

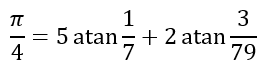

as derived by John Machin in 1706 or

as derived by Leonhard Euler in 1755. Of course, to evaluate the inverse tangent functions, both Machin and Euler would have had to use series similar to the one from the Maclaurin series. Using his equation, Machin obtained 100 digits for π, while Euler used his equation to obtain 20 digits of π in under one hour, a remarkable feat considering that this had to be done by hand!

Formulas such as the previous two are called Machin-like formulas and were very common in the era before computational devices like calculators and computers were invented. This finally led to the 620 digits of π calculated by Daniel Ferguson in 1946, which remains the record for a calculation of π done without using a computational device. Interestingly, in 1844 Zacharias Dase used a Machin-like formula to calculate π to 200 decimal places. And he did it all in his head! Now that’s not only some commitment, it’s a gargantuan feat of mental gymnastics!

Convergence of Machin-like Series

We can see why the Machin-like formulas converge more quickly than the original Gregory-Leibniz series. With x = 1, the powers of x are all identical. This means that the convergence is dependent solely on the slowly increasing denominators of the alternating series.

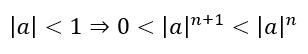

However, the Machin-like formulas, split x into smaller parts. And since

each subsequent term is dependent also on the convergence of a geometric series with common ratio between 0 and 1. Since the geometric series converges reasonably rapidly, all we have to do is determine an appropriate split, such as done by Machin and Euler. Naturally, the smaller the parts, the more rapid will be the convergence. Hence, even though

the Machin-like formulas use smaller fractions, like 1/5 and 1/239, as used by Machin, or 1/7 and 3/79, as used by Euler, to ensure much more rapid convergence.

Other Infinities

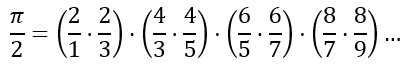

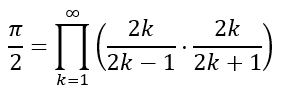

In addition to infinite series, which involve the summation of infinite terms, mathematicians have also derived infinite products. In 1655, John Wallis derived the equation involving the infinite product, known as the Wallis product, given by

which can also be written as

The derivation of this, however, requires an iterative formula. Hence, we will leave a further study of the Wallis product for the next post.

However, what we can understand from the study of π compared to what we discovered with e is that mathematicians are skilled at overcoming limitations by looking at things from a different perspective. There is a certain intuition and creativity involved in such innovative ideas and calls into question the unfortunately oft repeated untruth that mathematics is a purely left-brained activity.

Leave a reply to The Rewards of Repetition – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply