Coming Back Half Circle

We are in the middle of a series of posts on π. We began with A Piece of the Pi and followed it up with Off On a Tangent. In the first post I demonstrated that the definition of π is inadequate for the task of approximating the value of π. I then looked at a common approach to approximating the value of π using regular polygons. In the second post, I introduced the idea of infinite series methods to approximate the value of π and we saw what made some series converge quicker than others. In this post I wish to look at some iterative methods of approximating the value of π. The iterative methods, in general, tend to converge more rapidly than even the infinite series methods.

However, the mathematics behind these iterative methods is significantly higher than what I planned for this blog. Due to this, I will not give the details of the iterative methods but only give an outline to the methods, discussing how each step is accomplished and showing how the whole process fits together. However, that too will have to wait till the next post because laying the groundwork for the iterative methods will take the rest of this post!

Convergence of an Infinite Series

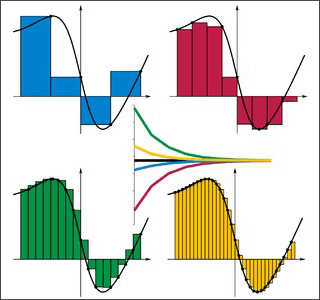

To begin with, let us consider the difference between an infinite series and an iterative process. In an infinite series, one must keep adding (or multiplying if the series if a product) more terms to bring the sum (or product) closer to the actual value of the number we are approximating. Since, for the series to be viable, it must converge, this means that each subsequent term of the series is smaller in magnitude. After all, given a sequence {an}, one condition for convergence is

This necessarily means that subsequent terms can only alter the approximation by increasingly smaller amounts, thereby essentially decreasing the speed with which the series converges. In other words, the very nature of a series means that it cannot converge as rapidly as we would want. A milestone calculation using an infinite series was in November 2002 by Yasumasa Kanada and team using a Machin-like formula (introduced in the previous post), resulting in 1,241,100,000,000 digits in 600 hours. In April 2009, the Gauss-Legendre algorithm that we will discuss in this post and the next was used by Daisuke Takahashi and team to determine 2,576,980,377,524 digits in 29.09 hours. We can see that this involves more than twice the number of digits obtained by Kanada and team in less than 1/20 of the time, indicating how fast the iterative process is. Why is this the case?

Convergence of Iterative Formulas

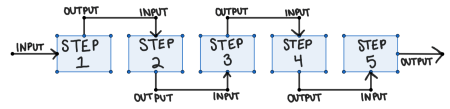

Iterative methods use current approximate values of the quantity to obtain better approximations of the quantity. To see how this works let us consider an iterative method used to obtain one of the iterative formulas for π.

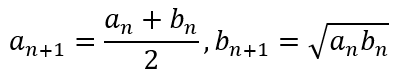

Given two positive numbers, a and b, the arithmetic mean (AM) and geometric mean (GM) of the numbers is given by

Now suppose we generate the iterative formula

All we need are starting values of a0 and b0 and we should be able to generate the iterative series.

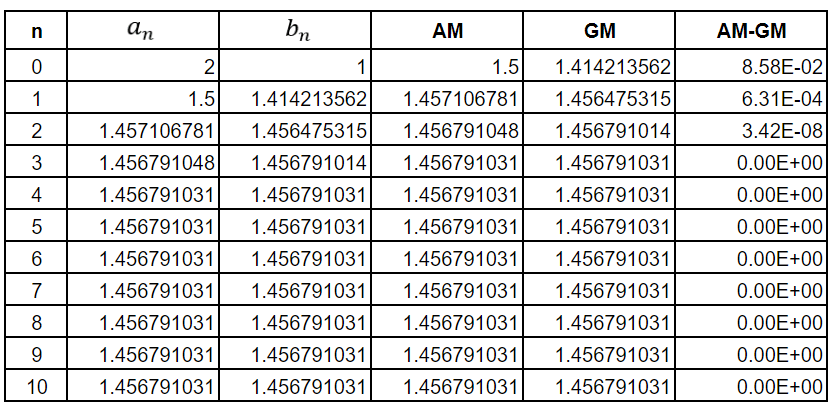

Suppose we choose a0 = 2 and b0 = 1. Then we get the following table

As can be seen from the last column, by the time we reach the third iteration, the AM and GM values have converged and are equal. Here I must observe that the final column betrays the inability of the Google Sheets computational engine to calculate beyond a certain lower bound for the error. Hence, the final column should be taken with a pinch of salt. The values of an and bn will never be equal if we start with different values of an and bn.

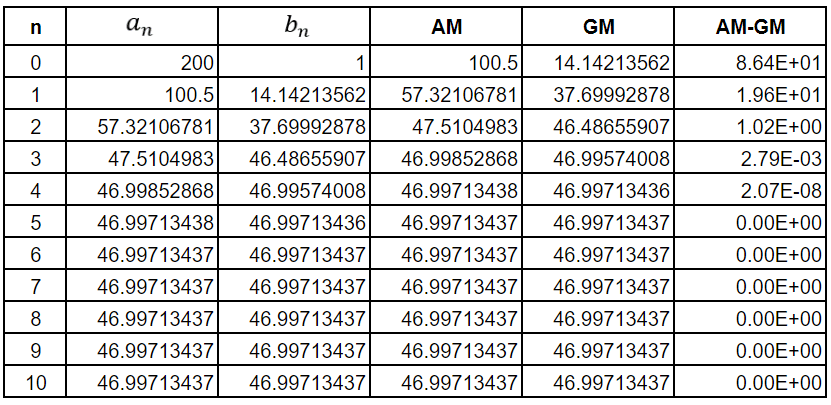

Suppose we start with the numbers a little further apart. Say a0 = 200 and b0 = 1. We would get the following table

As can be seen, the values of AM and GM have converged by the fifth iteration.

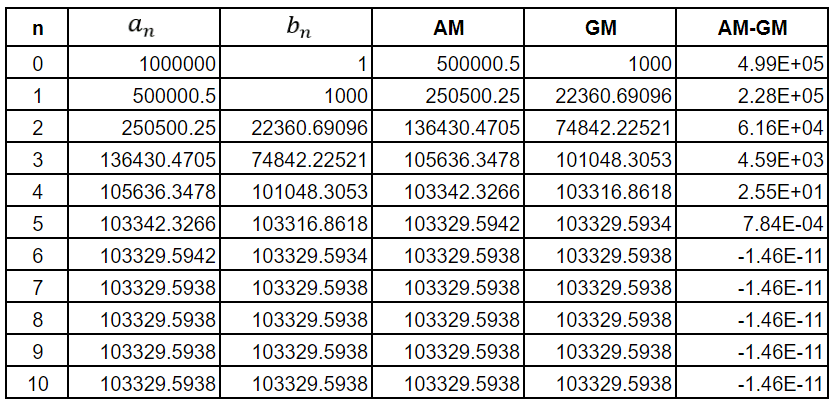

So what if we make a0 = 1,000,000 and b0 = 1? We would get the following table

This table reveals the limitations of the Google Sheets computational engine since all the errors after the 6th iteration are the same. This is impossible. However, you get the idea. The error between AM and GM has dropped to below 1 part in 10 billion by the 6th iteration.

The above tables demonstrate the rapid convergence of iterative formulas. And this fact of rapid convergence is used in most iterative methods for approximating π.

The Gauss–Legendre Algorithm

One of the first iterative methods is the Gauss–Legendre algorithm, which proceed as follows. We first initialize the calculations by setting

The iterative steps are defined as follows:

Then the approximation for π is defined as

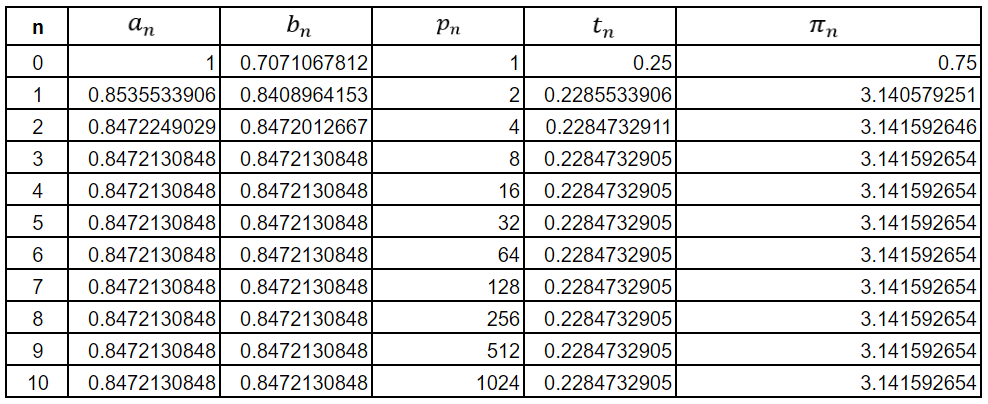

Using the algorithm, we get the following table

As can be seen, the Google Sheets engine is overwhelmed by the 3rd iteration itself. However, the approximation to π is already correct to 8 decimal places by then. In general, the Gauss–Legendre algorithm doubles the number of significant figures with each iteration. This means that the convergence of this iterative method is not linear, like the infinite series methods, but quadratic. The fourth iteration of the algorithm gives us

where the red 7 indicates the first incorrect digit, meaning that in 4 iterations, we have 29 correct digits of π, indicating how rapidly the method converges.

Wrapping Up

Quite obviously, many readers may be wondering how such iterative methods are found and how we can be certain that they are reliable methods for approximating π. In the next post, we will break down the Gauss-Legendre algorithm into the distinct parts. Some parts involve mathematics at the level of this blog and we will unpack those. For the other parts, which involve mathematics at a higher level than expected for this blog, I will only give broad outlines and the results. (I will provide links for readers who wish to see the higher mathematics.)

In the post after that I will look at some quirky infinite series and iterative methods that mathematicians have devised over the years. This will show us how creative mathematicians have had to be precisely because the definition of π is practically useless for approximating its value. This, of course, sets it apart from e, the definition of which is perfectly suited to obtaining accurate approximations of its value.

However, despite the rapid convergence of the iterative methods, most recent calculations, including the 202 trillion digit approximation of π done on 28 June 2024, use the Chudnovsky algorithm. We will discuss this powerful algorithm that involves a quirky infinite series in the post after the next. We will also consider why the Chudnovsky algorithm is preferred to iterative methods.

Leave a comment