A Brief Recap

Our journey into the wonders of complex numbers continues. In this series I hope to introduce the reader to the reality of complex numbers. In the previous post, we reached the stage where I introduced the square root of -1 as the unit of the imaginary numbers, parallel to the number 1, which is the unit of the real numbers. We looked at how addition, subtraction, and multiplication works with complex numbers. And I promised to look at division in this post.

Division of Irrational Numbers

Now, those who are familiar with mathematics taught till about grade 9 or 10, will know that the set of real numbers includes rational and irrational numbers. Further, a rational number cannot be irrational and vice versa. For example, numbers like

are rational because they can be expressed as the ratio of two integers. However, numbers like

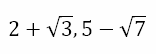

are irrational because they cannot be expressed as the ratio of two integers. Now, when we add or subtract one rational number and one irrational number, the result will be an irrational number. Hence, numbers like

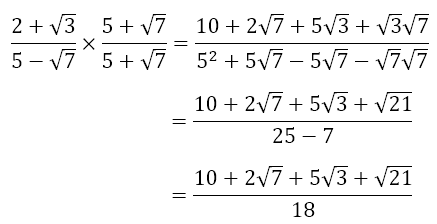

are irrational, with one part being rational and the other part being irrational. Now, if we were asked to divide one such irrational number by another, we would proceed with the method of rationalizing the denominator. So, if we were asked to evaluate

we would begin by multiplying the numerator and the denominator as follows to get

Note that the denominator has now become rational, which would allow us easier ways of manipulating the expression. The factor 5 + √7 is known as the irrational conjugate of the denominator 5 – √7.

Dividing Complex Numbers

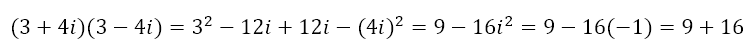

So, the irrational conjugate, when multiplied by the irrational factor results in a rational factor. Could it be, then, that a similar ‘complex conjugate’ could transform a complex number in the denominator into a real number? Before we try it on an actual division, let us see if the product of a complex number and its complex conjugate actually gives us a real number.

If we consider 3 + 4i, its complex conjugate (taking a hint from the irrational conjugate) would be 3 – 4i. When we multiply the two we would get

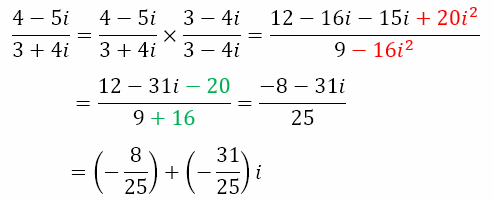

So, our intuition that multiplying a complex number and its complex conjugate would result in a real number was right. And this is because i2 = -1. Let us use this to divide one complex number by another. Let us divide 4 – 5i by 3 + 4i.

Note that the terms in red contain i2 and hence have a sign reversal, as indicated by the terms in green. Of course, the final result has the form a + bi, where a and b are real numbers. Hence, there is a real part, a, and an imaginary part, bi.

A New Perspective on Multiplication and Division

Now, it is all well and good that we managed to divide one complex number by another. However, whatever does the division mean? We know what division with real numbers means. For example 10 ÷ 5 can be viewed as the number of times 5 can fit into 10, giving the answer 2. We can also view it as a reduction of 10 by a factor of 5, giving 2. This allows us to see division and multiplication as, in essence, the same operation. Hence, division by 5 can be considered multiplication by 1/5. So both division and multiplication can be viewed as scaling a given number. Of course, as we have seen, negation, which can be viewed as a multiplication by -1, is nothing other than an anti-clockwise rotation about zero of 180°. And since division and multiplication are inverse operations, we can consider division by -1, which also is equivalent to negation, as a clockwise rotation about zero of 180°. Of course, a 180° rotation clockwise or anti-clockwise results in the same final position. However, we will see that maintaining a difference in direction of rotation makes sense when we consider complex numbers.

Now, while we have given some meaning, in terms of scaling and rotation, to multiplication and division of real numbers, how can this relate to complex numbers? From the previous post, we saw that we can visualize complex numbers on a plane with the horizontal axis depicting the real part of a complex number, while the vertical axis depicts its imaginary part.

The ‘Size’ of Real Numbers

However, viewing multiplication and division as scaling requires us to have some idea about the ‘size’ of the number. I mean it is only meaningful to say that division of 10 by 5 is a scaling of 10 by a factor of 1/5, resulting in 2, if we have some idea that the number 10 has 5 times the ‘size’ of 2.

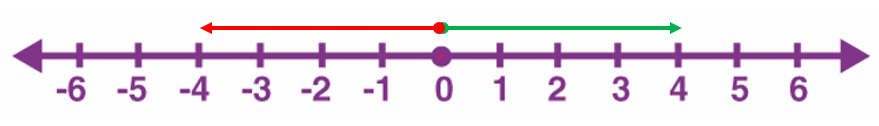

Of course, using the number line, we understand that the ‘size’ of a real number, also known as its absolute value, is the ‘distance’ of the point representing that number from the zero on the number line. Hence, the ‘size’ of both 4 and -4, shown below, is 4 units because the points representing 4 and -4 are 4 units away from the zero.

A Complex Cul-de-sac

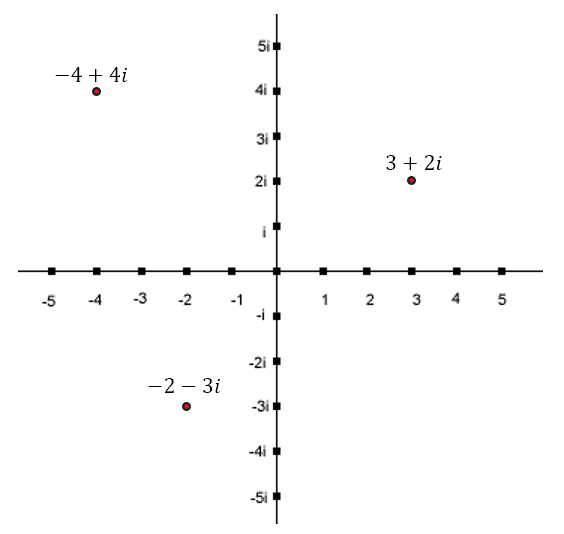

Now we saw that we can represent complex numbers on a two dimensional plane as below

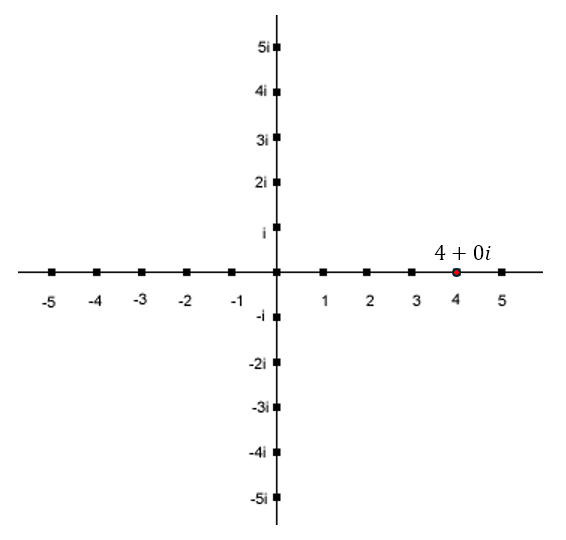

What ‘measure’ can we use to determine the ‘size’ of these numbers? We could simply add the distances moved in the real and imaginary directions. So the ‘size’ of 3 + 2i would be 3 + 2 = 5. Similarly, the ‘size’ of -4 + 4i would be 4 + 4 = 8. However, this measure is dependent on the orientation of the axes. For example, consider the point 4, depicted below

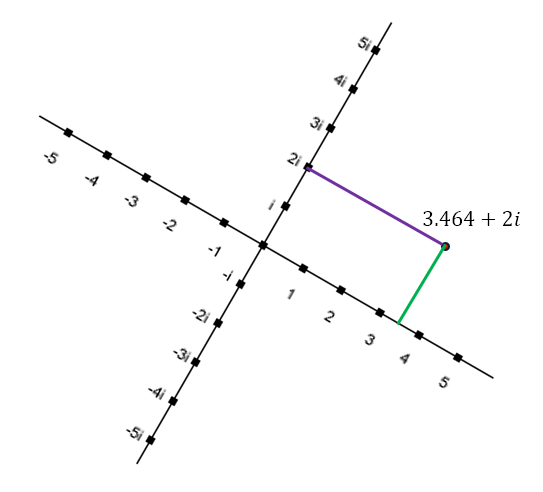

If we now rotate the axis by 30° clockwise, we will get the following

The distance from the imaginary axis will now be the length of the purple line, which happens to be 3.464 (rounded to 3 decimal places). The distance from the real axis will be the length of the green line, which is 0.5. Hence, as indicated, once we have rotated the axes, the new number becomes 3.464 + 2i, as indicated in the diagram. However, this means that the ‘size’ of the number is now 3.464 + 2 = 5.464. This means that a simple rotation of the axes has changed the ‘size’ of the number. We know that this is absurd. Changing the orientation of an object or our orientation with respect to an object should have no effect on the ‘size’ of the object. Hence, the measure involving simply adding the distances along the real and imaginary axes is a mathematically absurd measure.

Vectors Again to the Rescue

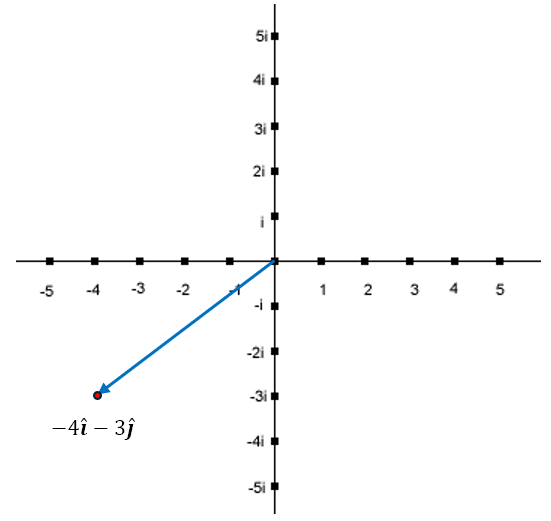

We could take a cue from the study of vectors, remembering that it was vectors that first gave us the intuition of adding another axis to depict the imaginary numbers. Now, the ‘size’ of a vector is known as its magnitude and is calculated using Pythagoras’ theorem. So if a vector depicts a move of 4 units to the left and 3 units down, we would first depict it as below

Please do not confuse i, the imaginary unit that is equal to √-1, and î, the unit vector along the x direction. While mathematicians have felt free to adopt letters from other scripts, such as α, β, θ, etc. from the Greek script, we still predominantly use the English alphabet. And there are only 26 symbols to choose from. So some overlap is to be expected.

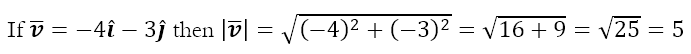

Anyway, the magnitude of the above vector (i.e. -4î -3ĵ) is determined using Pythagoras’ theorem as follows

The Modulus of a Complex Number

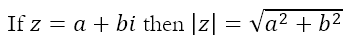

We now use the same method to define the ‘size’ of a complex number, which is called its modulus. Hence, the modulus of the complex number z = a + bi is defined as

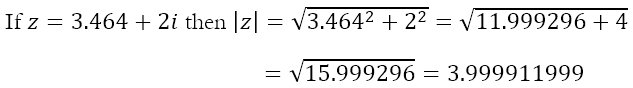

Does this hold up for the earlier experiment with rotating the axes? Recall that the original complex number was 4 + 0i. It is trivial to see that its modulus is 4. After rotating, the number became 3.464 + 2i. We calculate its modulus below

The final number, 3.999911999, might seem strange. However, this is the result of the rounding we had done earlier. Remember that the length of the purple line was 3.464 rounded to 3 decimal places. But how did I know if was 3.464? The measuring instruments I have at my disposal are an assortment of ruler, none of which has a least count smaller than 0.5 mm. So, if I used the rulers, I couldn’t have gotten anything better than 3.45 cm. What gives? Am I pulling the wool over your eyes? Absolutely not! You know I would not do that! So, there must be a way in which I have obtained the rounded value 3.464. Yes, indeed, there is. The actual value is 2√3, which the calculator gives as 3.464101615 and Wolfram Alpha gives as 3.46410161513775458705489268301174473388561050762076125611161395890386603381 to 64 decimal places. You can click on ‘More digits’ to get more digits, if that’s something you like to spend your time doing!

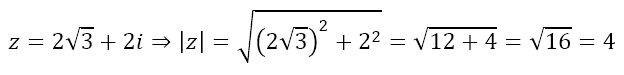

Of course, if the actual length of the purple line is 2√3, then the complex number is 2√3 + 2i, which would yield

Hence, with the exact value of the length, we get the same modulus for the complex number even after rotating the axes. Since, this is what we would expect, this definition of the modulus is what is accepted. But how did we obtain that the length was 2√3? In the first post of this series I had forewarned you that we would be making some pit stops along the way. Well, it’s time for one such pit stop, which I will deal with in the next post. Till then, modulate or remodulate yourself!

Leave a reply to Anticipating the Exponential Whirligig – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply