Recognizing a Limitation

As we continue with our pit stop in the series on complex numbers, let us remind ourselves where we have reached. In Trigonometric Identity Crises, we looked at some trigonometric identities. This followed on the heels of Round and Round, in which we saw why a right angle is defined to have 90°. We also defined the radian. Before that, in A Mathematical Partnership, we took a historical tour, starting from India and ending in Rome, during which we understood how the trigonometric ratios are defined and why they have their names. The pit stop began with the post that preceded it, My Trigger, No Metric, Beginnings, in which I explained my long standing fascination with trigonometry, beginning with my explorations with Pythagorean triples.

However, what we have seen so far is that the ratios are defined in terms of the lengths of sides of a right angled triangle. Now, students of Grade 6 (or maybe 7) and above will know that the sum of the angles of a triangle is 180°. This means that, in a right angled triangle, since one angle already is 90°, the other two need to add up to 90°. In other words, as defined, the ratios only work for angles that are acute, that is, strictly between 0° and 90°, not including both of them.

Now, since we can have angles that measure 0°, 90° and everything above 90°, including reflex angles, this means that the definitions of the ratios do not include most of the angles we may encounter. This is a serious drawback.

Descartes to the Rescue

Mathematicians do not like artificial restrictions. Hence, when faced with such an obstacle, they become creative and look for ways to circumvent the obstacle. In many such cases, the innovativeness involved is just mind boggling. Of course, since we are living some centuries after these innovations, we lack the ability to view them as something fresh that contributed to the advancement of mathematical knowledge. Indeed, hardly any teacher spends any time showing the students what the ‘before’ and ‘after’ of these innovations was, thereby impoverishing the students by depriving them of this knowledge.

In the case of extending the definition of the trigonometric ratios, the innovation involved is truly remarkable and underscores something I attempt to communicate to my students often, namely that the different branches of mathematics form one unified body of knowledge in which everything dovetails perfectly with everything else.

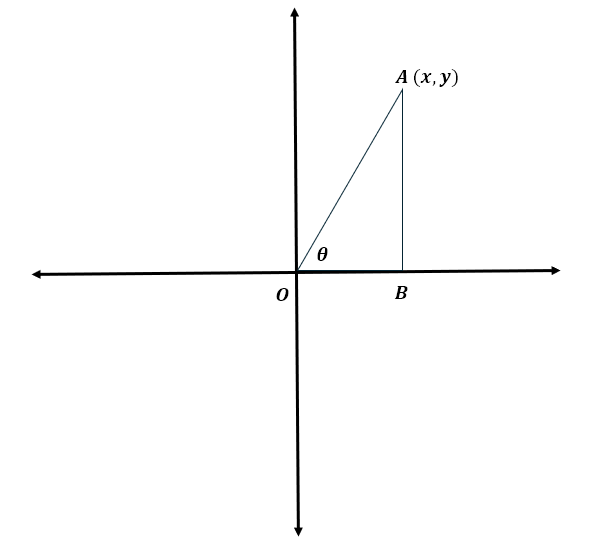

So let us see what they did. We begin with the Cartesian plane, named after René Descartes, the French mathematician. It consists of two number lines at right angles (we know what that means!) to each other and intersecting at their respective zero points. Now, let’s consider our right angled triangle. However, we place the vertex of interest at the origin of a two dimensional Cartesian plane, with one of the arms that forms the vertex aligned with the positive x-axis. This is shown below.

Beginning a Redefinition

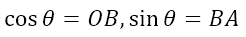

When we defined the ratios and understood why they have their names, we had considered a unit circle. In keeping with that, the hypotenuse of the triangle (side OA) is going to be 1 unit. Now, we can see that

Now, as indicated in the diagram, the point A has coordinated (x, y). However, the x coordinate of a point is the directed distance of the point from the y-axis. Similarly, the y coordinate of a point is the directed distance of the point from the x-axis. Since the term ‘directed distance’ may be unfamiliar to some, allow me to explain. If we start at the y axis and move toward the right to reach the point, then the distance is considered positive and the x coordinate will be positive. If, however, we more toward the left to reach the point, then the distance is considered negative and the x coordinate will be negative. In a similar way, starting from the x axis, an upward movement is considered positive, while a downward movement is considered negative. Hence, we can conclude that, to the right of the y-axis the x coordinates will be positive while they will be negative to the left of the y-axis. Also, above the x-axis the y coordinates will be positive while they will be negative below the x-axis.

However, with reference to the above diagram, it is clear that OB is the directed distance of A from the y-axis, while BA is the directed distance of A from the x-axis. In other words, the lengths OB and AB, both being positive in the above diagram, give the x and y coordinates of the point A. Hence, we can conclude that

In other words, with respect to the right angled triangle OAB, the cosine and sine of the angle at O are equal to the x and y coordinates of the point A.

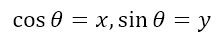

Now, let us revisit our Cartesian plane. Without any points on it, it would look like

Here, the Roman numerals (I, II, III, and IV) indicate the quadrant number. The signs below indicate the signs that the x and y coordinates have in that quadrant. Hence, in the second quadrant (i.e. II), the x coordinate is negative while the y coordinate is positive. This follows the directed distance convention we saw earlier – right/up is positive, left/down is negative.

Completing the Redefinition

We can see here that no quadrant has the same combination of signs for both the x and y coordinates. This allows us to extend the definition of the trigonometric ratios as follows. Consider a point (say P) on the circumference of the unit circle. Draw the radius joining P to the center O. Let the angle made by OP with the positive x-axis be θ. Of course, here we have the need for a further convention. Since any point on the circumference can be reached through a clockwise and an anticlockwise rotation, we define the anticlockwise rotation, that sweeps the quadrants in proper order, to be a positive angle measure. Hence, a clockwise rotation would be a negative angle measure.

Anyway, let the angle made by OP with the positive x-axis be θ. Then we define the cosine of θ to be the x coordinate of P and the sine of θ to be the y coordinate of P. We can depict this as follows.

Ratios for Allies

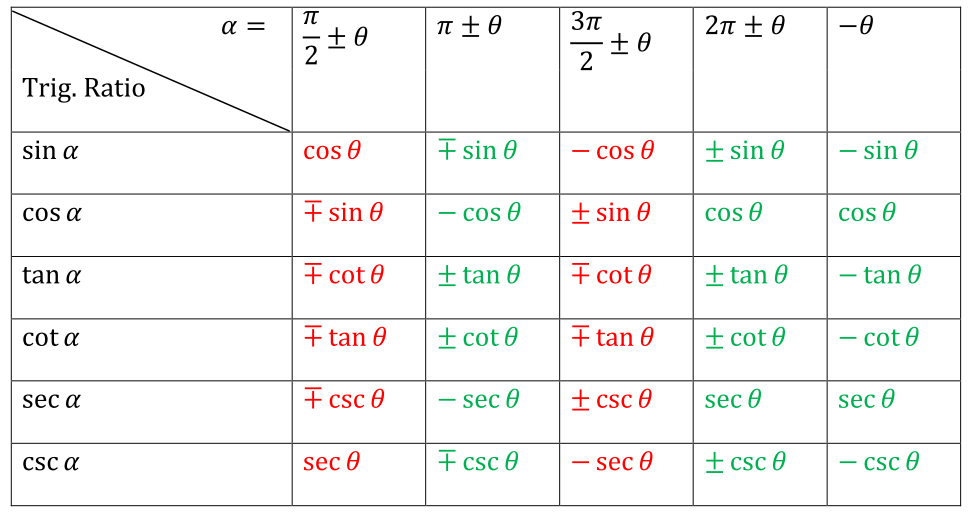

We can see that, since the angle made by the axes with each other is 90° (or π/2 radians), angles that differ by or add to multiples of 90° (or π/2 radians) will have trigonometric ratios that are related to each other. Such pairs of angles, which differ by or add to multiples of 90° (or π/2 radians) are called allied angles. Using these extended definitions, we can obtain the following results

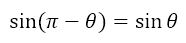

The above table may be a little confusing. For starters, I have used radian measures for the angles. Recall that 180° = π radians. So, let’s see how the table is to be read. Suppose I want to determine sin α, where α = π – θ. The row for sin α is the second row of the table, while π ± θ is the third column. The element in that cell is ∓ sin θ. Since I am interested in π – θ and the minus sign is second in the symbol ±, I take + sin θ, which is second in the term ∓ sin θ. Hence, I can conclude that

How do we obtain these results? If you are interested, you can find visual proofs using a general, not unit, circle here. With our extended definitions of the trigonometric ratios, we can obtain their values for any angle. If you wish to see this for yourself, you can check here, here, and here.

Rotations Without End

Now, of course, we are treating angles as though they were also on somewhat of a number line, just one that wraps around itself. We have adopted the convention that counterclockwise rotations are positive and clockwise rotations negative. Also, we realize that there is nothing that hinders a radius from continuing to rotate beyond the full cycle. So we could have angles that exceed 2π radians (360°) and angles that go below -2π radians (-360°). An angle of 7π radians, for example, would involve three full counterclockwise rotations, each of which accounts for 2π radians, followed by a further rotation by π radians. Similarly, an angle of -810° would involve two clockwise rotations, each of which accounts for -360°, followed by a further rotation of 90°. Of course, with each rotation, the point P will reach identical positions as in the previous rotation. This means that, after every rotation, the values of the trigonometric ratios repeat themselves. This is a feature known as periodicity, which is crucial in the study of complex numbers. Since it is a very important part of the study of trigonometry, we will turn to that in the next post. Till then, keep twirling!

Leave a reply to Concluding Uncomplex Pitstop – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply