Back on Track

As we continue our series on complex numbers, we return to the main series of posts, having concluded what I called a ‘pit stop’ last week. The pit stop introduced us to trigonometry. It should be observed that I have only introduced trigonometric ideas that contribute to our understanding of complex numbers. There is much more that we could have studied. Perhaps at a later date, I will revisit trigonometry and take us beyond to some fascinating results, such as conditional identities and the properties of triangles. Anyway, let us trudge back to our study of complex numbers.

Revisiting the Modulus

When we began our pit stop on trigonometry, we had just introduced the idea of the modulus of a complex number. Hence, we saw that, given the complex number z = a + bi, the modulus is defined as

We saw that this way of defining the modulus is not affected by the rotation of the axes. In other words, this metric is invariant to the rotation of the axes. Of course, if we rotate the axes, the orientation of the complex number with respect to the axes will change. In other words, even though the modulus is invariant, the orientation is not. This is only to be expected since the orientation is determined in relation to the axes and the axes are rotating.

Numbers on the Complex Plane

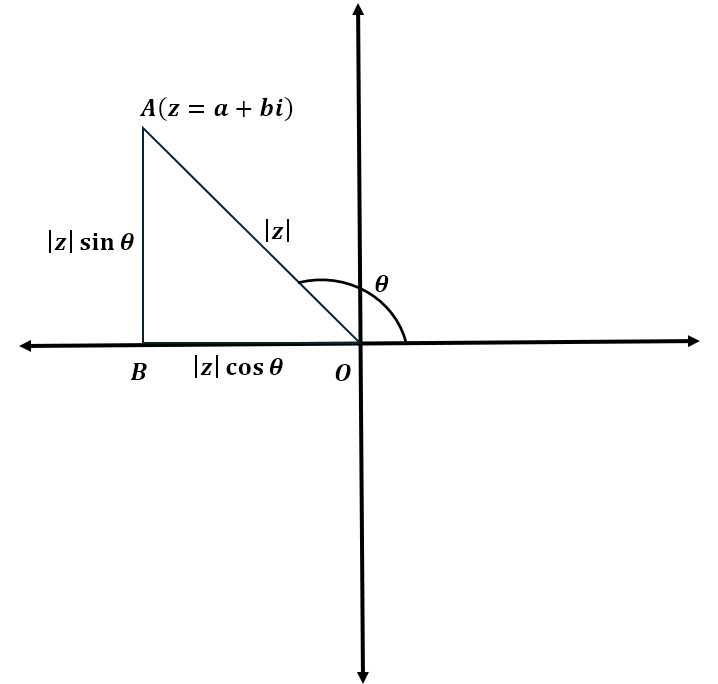

However, given a complex number z = a + bi, it is clear that this number represents a units in the real direction and b units in the imaginary direction. Hence, the point representing z on the complex plane is fixed. We can, therefore, join this point to the origin with a line that is unique to the point and, hence, this line makes a unique angle with respect to the positive real axis. This is depicted in below.

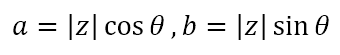

In the above diagram, we can see that the real and imaginary parts of z can be written as

Introducing the Argument

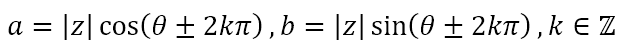

Hence, the above complex number has an orientation equal to θ with the positive real axis. This angle θ is called the ‘argument’ of the complex number. Now, since the trigonometric ratios are periodic in nature, we can also conclude that

In other words, due to the periodic nature of the trigonometric functions, which is something obtained from repeated rotations about the center, there are infinitely many values of the angle that will land us on the same point on the complex plane. However, there is a unique angle with the smallest magnitude that gives the same orientation. This angle is called ‘the principal value’ of the argument and will take values between –π and +π. Let us see how this works.

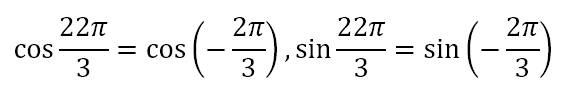

Suppose I have a complex number that I have obtained as follows: It has a modulus of 8 and an argument of 22π/3. Since the argument is great than π, I repeatedly subtract 2π to get

Due to this we can conclude that

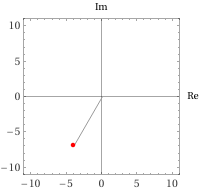

Since the angle now lies between –π and +π, it is the angle with the smallest magnitude that gives us the same orientation. Hence, while we can say that the same complex number can have arguments of 22π/3, 16π/3, 10π/3, 4π/3 and -2π/3, the principal argument of the complex number is -2π/3. Where would this complex number lie on the complex plane? All we have to do is calculate the real and imaginary parts and plot the point. This is shown below

Till now we have specified complex numbers in terms of their real and imaginary parts as a + bi. This is known as the Cartesian form, since it depends on the system similar to the normal Cartesian coordinates in which we have two axes intersecting at right angles. Of course, since the modulus and argument of a complex number specifies a unique point on the plane, we can represent the complex number in terms of these two numbers. Hence, the above complex number can be written as (8, 22π/2), where the first number specifies the modulus and the second the argument. This is known as the polar form of the complex number. By convention, the modulus is denoted by r, since the complex number having a modulus of r lies on the circumference of a circle of radius r centered at the origin.

Adding and Subtracting with the Polar Form

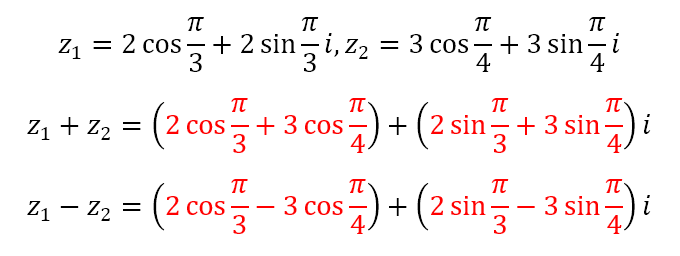

Now, let us see what happens when we add and subtract complex numbers using polar coordinates. Consider two complex numbers z1 = (2, π/3) and z2 = (3,π/4). Here, the complex numbers have been specified in polar form. We can obtain the following

Now, the terms in red are clunky. And there are no trigonometric identities that would help us reduce these to forms that are neater. So, why bother with the polar form if all it does is give us clunky terms? I’m glad you asked.

Multiplying and Dividing with the Polar Form

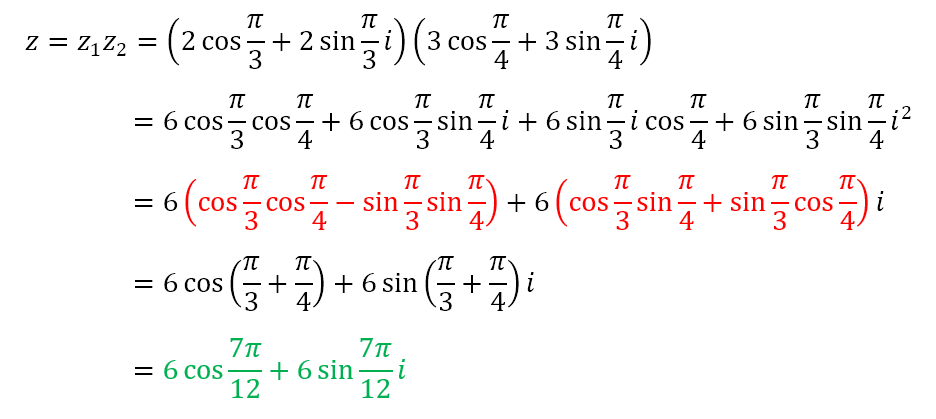

The power of the polar form lies in what it does when we multiply and divide complex numbers. Let us consider the same two complex numbers and see what happens when we multiply them.

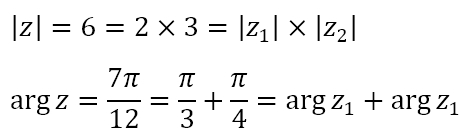

To get from the third to the fourth lines we used the sum formulas that we obtained in the previous post for the terms in red. Of course, from earlier in the present post we can recognize that the terms in green are simply the complex number z = (6, 7π/12). However, note the following

That is, when multiplying complex numbers, their moduli get multiplied and their arguments get added. That is really convenient and reduces the effort of multiplication considerably. Knowing the two moduli were 2 and 3, we could right away conclude that the modulus of the product is 6. And knowing that the two arguments were π/3 and π/4, we could easily determine that the argument of the product is 7π/12.

The same power is evident when we try to divide two complex numbers. We should be able to infer that, when dividing z1 = (2, π/3) by z2 = (3,π/4), the result should be a complex number with modulus equal to 2/3 and argument equal to π/3 – π/4 = π/12. Mimicking college mathematics textbooks, I leave the proof to the reader!

Looking Ahead

What we have seen is that the polar form of complex numbers significantly simplifies multiplication and division. Addition and subtraction, however, are not really improved at all and may, in many cases, be actually more tedious. However, the polar form has more advantages as we will see in the next post. That will be two weeks from today as I will be taking a break next week for Holy Week and Good Friday.

Leave a reply to Anticipating the Exponential Whirligig – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply