A Forty Year Fascination

I was in the eleventh grade when I was introduced to a part of analytical geometry (or coordinate geometry, if you wish) that would fascinate me over the years. Don’t get me wrong. When I first learned about this aspect of analytical geometry, which is now almost forty years ago, I did not give it much thought because the teacher I had made the subject so dry that it was a educational desert! All he did was rattle off formulas and derivations without pausing even a bit to explain the significance of what he was doing. And if someone like me, who really enjoyed mathematics, was bored out of his wits in those classes, I can only imagine how akin to some fantastical ‘undead’ many of the other students were driven to become.

The problem with mathematical education in high school, as I have explained elsewhere, is that the syllabus is bloated. It includes far too much that is superfluous or unnecessary for the development of mathematical skill and intuition. As a result, some parts of the syllabus, like the one I’m writing about, which combine different areas of the syllabus in a lyrical dance of mathematical insight, are often given short shrift, probably because the teacher himself/herself has failed to learn the dance steps.

I am, of course, referring to the study of conic sections. I am grateful to many of my own students who asked me many questions and served as catalysts to fuel the love for this part of mathematics in me. This love, however, was first kindled when I was in the second year at the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay. That was in 1988-1989 and I was doing a project for a professor on Synthesis of Coupler Curves. Anyway, my study of coupler curves led to an appreciation of the conic sections, which later helped me when I myself began to teach.

Some of you may be wondering what a ‘conic section’ is. Fair point. It’s not a mathematical term you often come across. In fact, unfortunately, there are many syllabuses around the world in which students study the conic sections without being told that they are studying things that are called conic sections. So, what is a conic section? Simply put, a conic section is a two-dimensional curve obtained by intersecting (hence ‘section’) the surface of a cone (hence ‘conic’) with a plane. That is, if you cut the surface of a cone with a plane, the resultant boundary of the surface of the cut cone is a conic section. This is shown in the figure below.

As the figure indicates, the commonly referenced conic sections are the circle, the ellipse, the parabola, and the hyperbola. I would add pair of lines to this, formed by sectioning the cone through its apex. In this series of posts I wish to study these five conic sections, introducing us to their properties and idiosyncrasies. In this post I simply want to deal with one issue – how do we represent a conic section analytically?

Enter the Equation

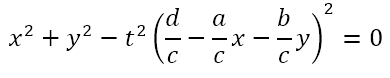

The teacher who first introduced me to the conic sections did not tell me and my classmates this. He simply told us that the general second degree equation in two variables is the general equation of a conic section. So he wrote

on the board, gesticulated at it and told us that this was a general second degree equation in two variables and that it represented all conic sections. Of course, if you give it some thought, you will realize that, since there are two variables (x and y), this was an equation in two variables. Further, since the highest power of either variable (x2 and y2) or variables combined (xy) was 2, this was a second degree equation. Finally, since it contains all possible terms containing x and y with degree not greater than 2, this was the most general form of a second degree equation in two variables.

But this did not explain why this represented all the conic sections. When I asked my teacher, he just repeated that it did! I was quite frustrated at having my curiosity snubbed in this manner. I laid the matter to rest and picked it up only many years later when a student asked me the same question. Given that I had been snubbed for asking the question, I could not do the same to m student. So I decided to understand why the above equation represents conic sections.

Unfortunately, none of the resources available explained the why behind the fact that the equation represented conic sections. So I decided that I would undertake this exploration myself. And I realized that the answer is actually quite simple. It is so simple that the resources must either simply be taking this understanding for granted or have themselves not bothered to understand why the equation represents all possible conic sections in the two-dimensional plane. So let us provide some clarity.

Understanding Intersection

We begin with the equation of a straight line. We can write it as

Here, m is the slope or gradient of the line and c is the y-intercept. What this equation tells us is that, if we are given the value of x, in order to find the corresponding value of y we need to multiply x by m and then add c. This will give the point (x, y) that satisfies the equation. Since the above equation is linear, that is the highest degree of the variables is 1, it represents a straight line. Hence, ‘linear’. Now, what if we have two lines, say

These are two linear equations. If we find the values of x and y that satisfy both equations, we are said to ‘solve’ the system of simultaneous equations. However, looking at this from the perspective of geometry, this mean that the solution x and y represents the point (x, y) that lies on both lines. This is a remarkable insight. What this tells us is that, if we have two curves that can be represented by

then solving the equation

will give us the values of x that satisfy both equations simultaneously. From a geometric perspective, the solutions represent the x coordinates of the points that are common to both curves. Of course, having obtained the values of x, we can use either equation to obtain the corresponding values of y. Suppose we obtain solutions

We can substitute these values of x into either equation to obtain the values of y as

This means that the points

are common to the graphs of both functions. They are the points at which the graphs of y = f(x) and y = g(x) intersect. In the language of conic sections, the graph of y = g(x) sections the graph of y = f(x) at the points listed above. Let’s keep this in mind for later when we start to section the cone with a plane.

Equation of a Plane

When we move to the plane and the cone, we need to describe them in a three-dimensional space. Let us first obtain the equation of a plane in general form.

Suppose we have just one number line. We can represent one variable, say x, on this number line. If we had the equation ax = b, this would represent a point. In other words, when we have a one-dimensional ‘space’, that is the single number line, a linear equation represents a zero-dimensional object – a point.

When we consider our normal two-dimensional space with x and y axes, we understand that an equation of the form ax + by = c represents a straight line. In other words, when we have a two-dimensional ‘space’, that is a plane formed by two number lines, a linear equations represents a one-dimensional object – a line.

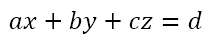

We can extend this and conclude that, given a three-dimensional ‘space’, that is one in which we can represent three variables, x, y, and z, then a linear equation ax + by + cz = d will represent a two-dimensional object, that is, a plane.

Equation of a Cone

Now that we have obtained the equation of a plane, let us do the same for a cone. What exactly is a cone? Most definitions online are absolutely useless because they define a cone in terms of what we know about a cone, namely that its surface is conical! Well, no resource actually has such an evidently circular definition. However, given the actual words they use, they might as well have had such a circular definition.

Technically a cone is obtained by fixing one point on a straight line and rotating it about that point at a constant angle with respect to a fixed straight line passing through the fixed point. The fixed point is then the apex of the cone and the fixed straight line is its axis.

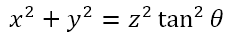

Let us consider a cone with apex at the origin and axis being the z-axis. Consider the generating line to make an angle θ with the z-axis. Then a point on this line with z coordinate of z, will have a distance from the z axis equal to z tan θ. Now when the line is rotated about the z axis, the point will trace a circular path with center on the z axis and radius equal to z tan θ. In other words, if the moving point has x and y coordinates equal to x and y respectively, then

Sectioning the Cone

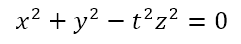

Suppose we replace tan θ with t, then the equation above becomes

Suppose we are sectioning the cone with the plane given by

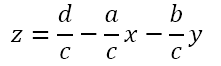

We can rearrange this as

Substituting this expression for z in the equation of the cone we get

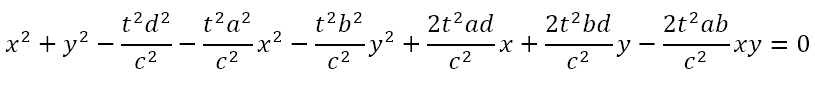

We can expand the square to get

Multiplying the whole equation by c2 and grouping terms we get

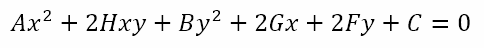

If we make the substitutions

the solution equation becomes

Search for Oases in the Desert

Apart from the upper case letters, it is clear that this equation is identical to the earlier general second degree equation in two variables. In other words, when we solved the equation of the cone with that of the plane, what we obtained was the general second degree equation in two variables. Since the process of solving two equations gives the points that satisfy both equations, this means that solving the equation of the cone and the plane will give the points that lie on the cone and on the plane. However, the points that lie on the cone and the plane are precisely the points on the surface of the cone that are sectioned off by the plane. In other words, the solution of the two equations must represent the sectioning of the cone, that is, the conic section.

Of course, there are six parameters (A, B, C, F, G, and H) that will affect the kind of conic section as well as the size, position and orientation of the resultant conic. In this series we will attempt to study each of the conic sections in the hope that this study will prove to be an oasis in the desert that analytical geometry can often be. We will continue the search for these oases in the next post, when we will look at the conic section that every student learns about in school – the circle.

Leave a reply to A Mathematical Straight Couple – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply