Revisiting the New Kind of Number

We are in the middle of a series on complex numbers. I started this series with Primer to Complex Numbers, in which I shared some basic algebra tools that we would need for our exploration of complex numbers, ending in a brief discussion about the importance of the discriminant. In the second post, A New Kind of Number?, I continued with the exploration by looking at what the discriminant tells us about the kind of numbers we are considering. That discussion included the idea that negation could be considered an anti-clockwise rotation about zero of 180° rather than a reflection in zero. Quite obviously, rotation would mean ‘stepping out’ of the constraints of the number line into a new realm. What would that entail?

Operations with the ‘Normal Numbers’

We begin by considering this new kind of number as something that cannot be combined in normal ways with the numbers we normally encounter. For example, we know that the basic mathematical operations can be performed on all our normal numbers. So, for example, we know that 11 and 12 can be added to give 23; that 13 can be subtracted from 10 to give -3; that 3 can be multiplied by 16 to give 48; and that 50 can be divided by 6 to give a quotient of 8 and a remainder of 2.

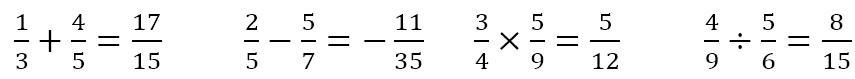

We do not have to restrict ourselves to integers, though. We know that the following are all valid

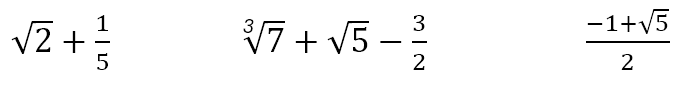

We do not even have to restrict ourselves to rational numbers. In fact, the expressions

can be evaluated to any desired degree of accuracy simply by calculating each irrational number and performing the necessary operations after that. This works even for the transcendental numbers, like e and π. For example, while it may be difficult to evaluate by hand, a computer could give us the value of the expressions below to any desired level of accuracy.

In all the above cases, the operations, while in some cases extremely tedious, we possible to carry out. Furthermore, we had a clear idea about what these operations meant since all the numbers could be located on the number line.

However, if we were now proposing that we escape the confines of the number line, what exactly are we attempting to do?

Assistance from Mechanics and Vectors

When students in school learn mechanics, either in the context of physics or mathematics, their study of motion is first confined to motion in a single dimension. A particle is considered to move along one axis, normally not even named since there is only one dimension of motion. However, since most motion in real life is three dimensional, the single dimension proves to be too unrealistic a constraint. Students are then introduced to motion in two dimensions, the most common case considered being that of a projectile, like a ball, being thrown at some angle of incline.

Students are taught a key concept when studying motion in two dimensions – the vertical and horizontal dimensions are orthogonal to each other. The basic meaning of this is that the vertical and horizontal dimensions are at right angles to each other. However, there is a deeper insight to be gained: No horizontal motion will contribute to vertical motion and vice versa. In other words, what happens horizontally does not affect and is not affected by what happens vertically. This allows the students to study the motion in each direction separately before combining the results to describe the motion as a whole.

This forms the basis of the study of vectors too. We conceive of mutually perpendicular axes so that we can isolate what happens along one axis from what happens along other axes. In both cases, what we are saying is that what happens in one dimension or axis is cannot be combined with what happens in another dimension or axis, but must be kept distinct.

We express this technically by saying that vertical and horizontal motion are independent of each other. Similarly, the x and y directions are independent of each other. And this is all because the directions are at right angles to each other.

The Imaginary Unit

We now use this same insight to think of this new kind of number, which when squared can give a negative result. We recognize that all the numbers we normally encounter do not change when multiplied by 1. In other words

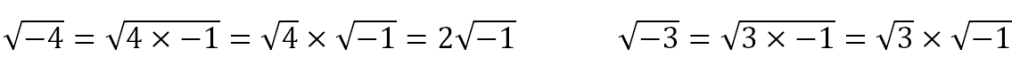

We, therefore, consider the number 1 as the ‘unit’ of the normal numbers. Further, when faced with the square root of a negative number, we recognize that we can do something like the following.

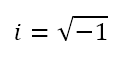

In other words, we recognize that any negative number can be written as the product of its absolute value and -1. Now, we proceed to define the square root of -1 as the ‘unit’ of the new kind of number. By convention, we will denote it as i. In other words,

Linking the Normal and New Numbers

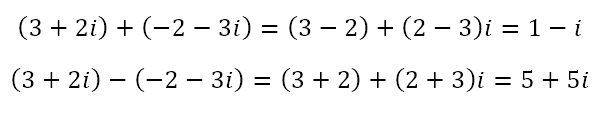

Now, we allow ourselves to perform operations with the new numbers as usual, but ensuring that the normal numbers and the new numbers are never combined to as to lose their distinctiveness. So, for example, we can do the following.

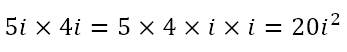

But what would happen if we tried to multiply these numbers? We would get the following.

The above rearrangement is legitimate because multiplication is commutative. However, note that we have the square of i at the end. From the definition of i as the square root of -1, we should have

However, note that -1 is a normal number. In other words, by squaring the new number, we get a normal number. But not just any normal number! Rather, we have obtained the negation of the ‘unit’ of the normal numbers. Recall that we had defined negation as an anti-clockwise rotation about zero of 180°. This would indicate that i, the unit of the new numbers, is obtained by an anti-clockwise rotation about zero of 90°, as a result of which squaring would involve two such rotations for a total of 180° as required by the result that

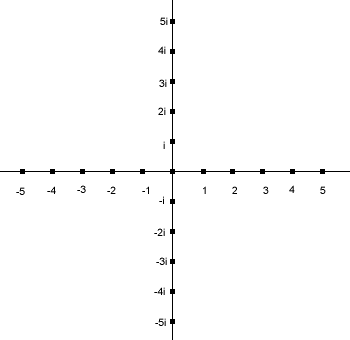

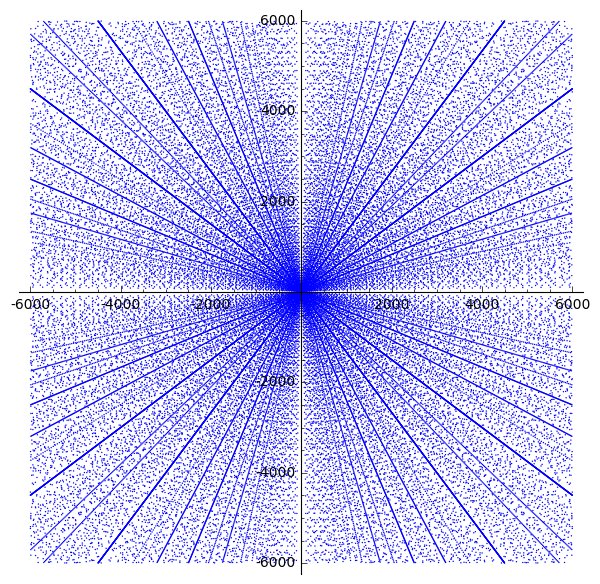

So what we have obtained in that 1, the unit of the normal numbers, and i, the unit of the new numbers, are oriented at right angles to each other! In other words, 1 and i are independent of each other. Since the normal numbers have their own number line, we define another number line for the new numbers that is at right angles to the original number line. Also, since

we realize that zero can be written as a normal number and as a new number. Hence, the two number lines will intersect at zero. We can depict this as below.

Operations in the Complex Plane

Now, I have to stop using ‘normal numbers’ and ‘new numbers’ simply because these are not the accepted conventions for referring to them. However, with respect the the above diagram, the normal numbers, known as ‘real numbers’, are represented along the horizontal or real axis, while the new numbers, known as ‘imaginary numbers’, are represented along the vertical or imaginary axis. The entire plane, consisting of the two axes, is known as the ‘complex plane’, another unfortunate term.

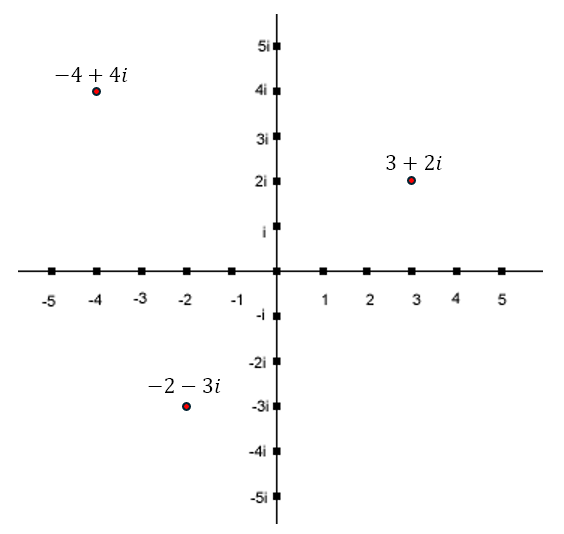

Numbers that are a combination of real and imaginary numbers can be located on the plane as shown below

We can describe the above numbers as follows:

- 3+2i : Starting from the zero on both axes, move 3 units to the right and 2 units up.

- -4+4i : Starting from the zero on both axes, move 4 units to the left and 4 units up.

- -2-3i : Starting from the zero on both axes, move 2 units to the left and 3 units down.

Since the real and imaginary axes are perpendicular to each other, they are independent of each other. Hence, we can add and subtract as follows

This is because moving 3 units to the right and 2 units up followed by 2 units to the left and 3 units down, is, in effect, to move 1 unit to the right and 1 unit down. Also, moving 3 units to the right and 2 units up followed by the reverse of (i.e. negation of) two units to the left and 3 units down, is, in effect, to move 5 units to the right and 5 units up.

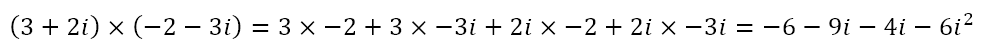

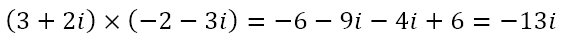

When it comes to multiplication, however, we encounter a new phenomenon. It is meaningless to talk about multiplying directions. Hence, it is absurd to say that two upward directions multiply to give a leftward direction. However, when it comes to numbers, we saw that negation can be considered as an anti-clockwise rotation about zero of 180°. Further, we saw that i can be considered an anti-clockwise rotation of 90°, allowing for the square of i to be equivalent to negation. This means that it is legitimate to multiply complex numbers and we can do this using FOIL (see Primer to Complex Numbers) as below.

However, since the square of i is -1, we can simplify the above as

The Fork Ahead

So far we have seen that it is possible to conceive of imaginary numbers and real numbers as two quite different species of numbers that are independent of each other. Due to this, they can be added and subtracted in the conventional way with the only restriction being that we keep the real and imaginary parts separate. However, when we conceive of the real and imaginary numbers as independent, we face a corollary that the square of i is equivalent to negation. This gives us the justification for multiplying complex numbers using conventional algebraic rules.

This also explains the title of this post. No, I did not make a mistake. Yes, I have combined two ideas – rocket science and brain surgery – that normally do not go together, much like the real and imaginary numbers. Not everything is smooth, as we will see. However, with the single insight that squaring the imaginary unit is equivalent to negation, we can actually make the two otherwise disparate elements work together.

Of course, there is much more to complex numbers. We still have to give further meaning to multiplication. We also have to see how division would work, not to mention exponentiation. And that is just the start. There is so much that the imaginary numbers open up for us and I hope you are as excited as I am for the journey ahead. In the next post, we will consider how division works with complex numbers. Till then, I won’t say, “Stay real” but “Stay true.”

Leave a reply to Concluding Uncomplex Pitstop – Acutely Obtuse Cancel reply