Presenting Problem

I recently came across the following problem: Eight lamps, each with an on-off switch, are arranged in a circle. A lamplighter can flip (in other words, change the state of) the switches, but he is not allowed to flip just one at a time. When he switches lamps on or off, he is required to flip the switches of three consecutive lamps simultaneously. (For example, he can flip the switches of lamps G, H and A at the same time.) Prove that no matter what set of lamps was turned on at the start, the lamplighter can turn all the lamps on.

Recognizing the Requirement

Since we are entering the Christmas season, which is a season of lights, I wish to tackle this specific problem and then extend it to a more general situation. Now, since the final state of all the lights is the same with all being on is accomplished regardless of the initial state of the lights, it must mean that it is possible to change the state of any particular light after a finite number of moves. Then we can repeat the process as needed to change the state of every light that is currently off so that it is on. In effect this means that we are able to transform any starting pattern to any other desired pattern with a finite number of steps, each of which consists of flipping three switches.

Initial Proof

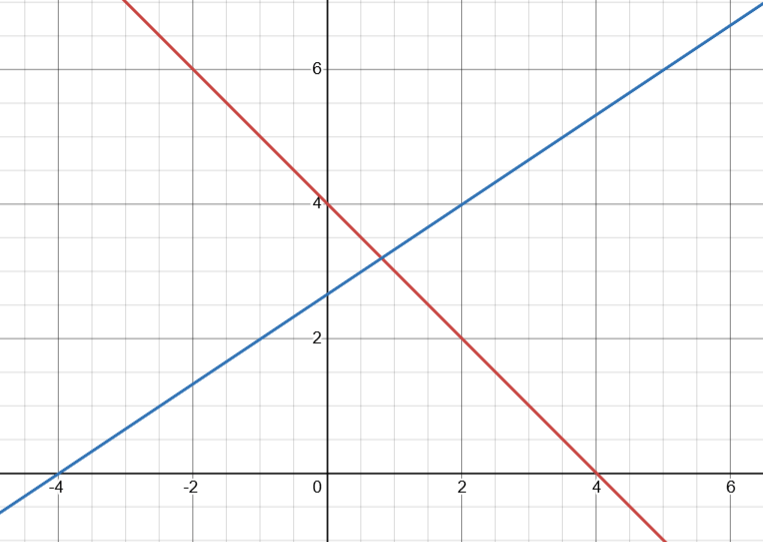

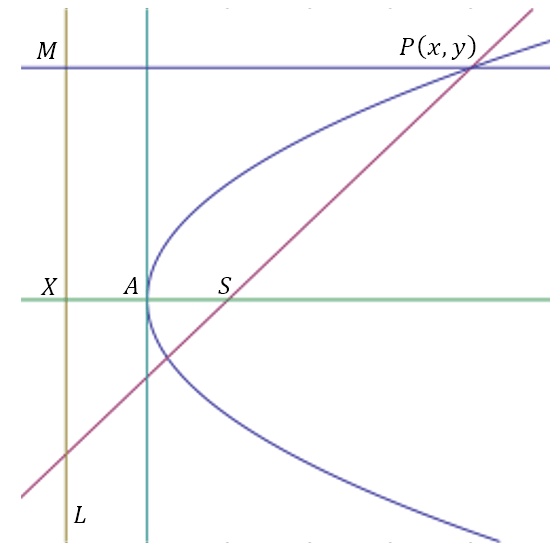

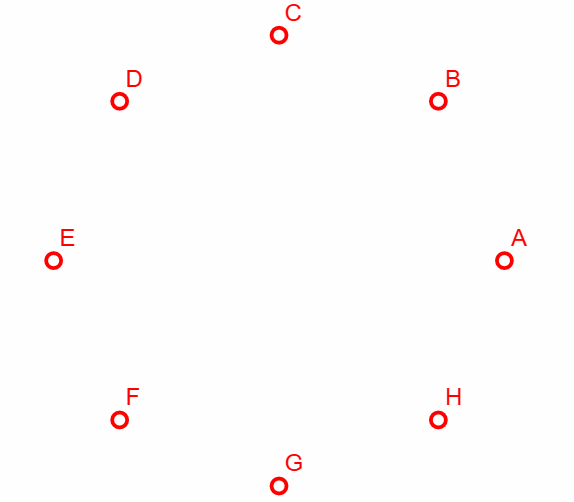

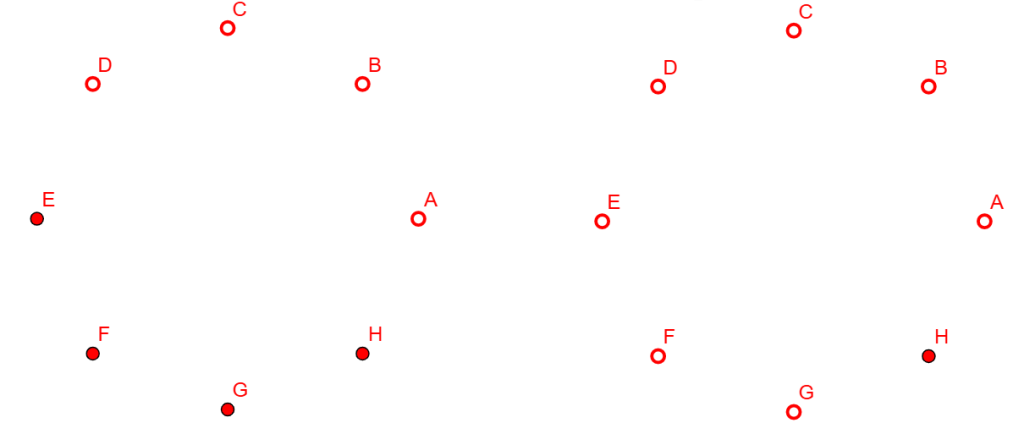

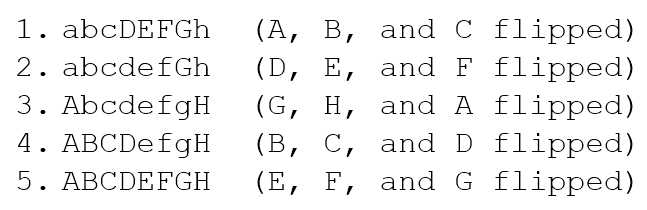

To begin with let us just assume that all the lights are off. This is shown in the figure below.

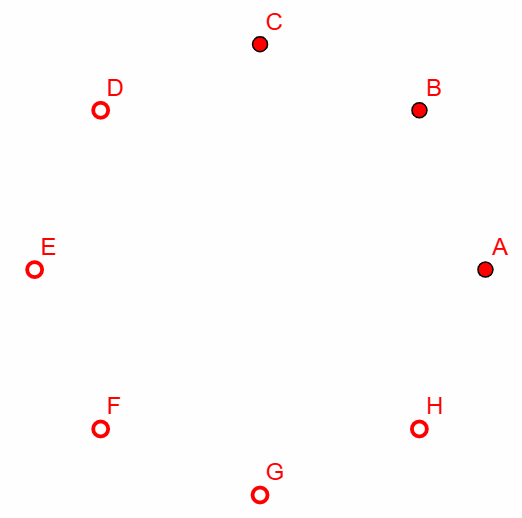

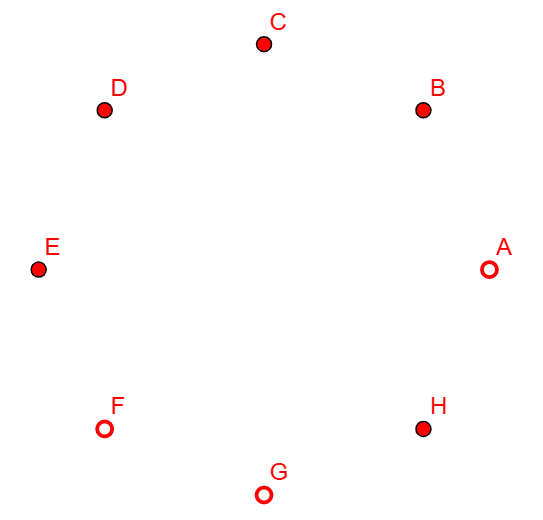

Here, I am adopting the convention that a filled-in circle represents a light that is on. Hence, an empty circle is a light that is off. Now, the challenge is to use a finite number of moves to change the state of one and only one of the lights. Let us arbitrarily start at A. Hence, we have to flip the switches A, B, and C. This will give us

Now, we can flip the switches D, E, and F to give us

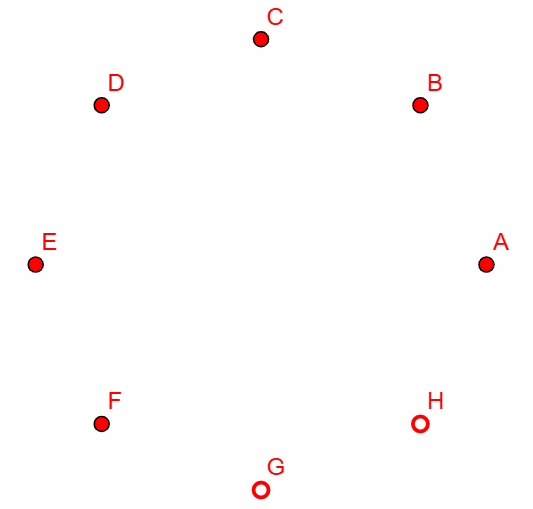

Finally, we can flip the switches G, H, and A to give

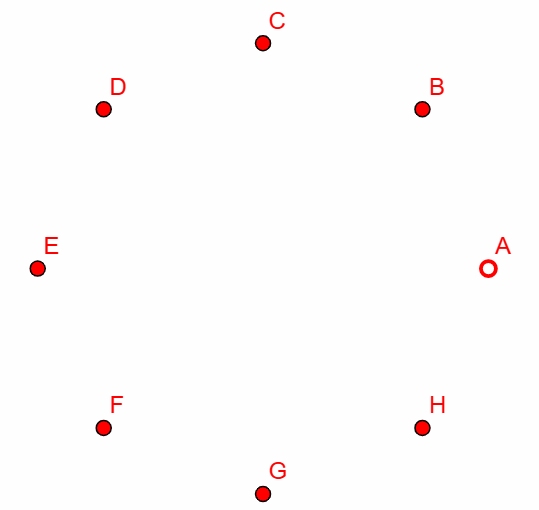

We can see that, after three switching sets we have actually managed to alter the state of all the lights except A. If we continue this process, the next two outcomes will be:

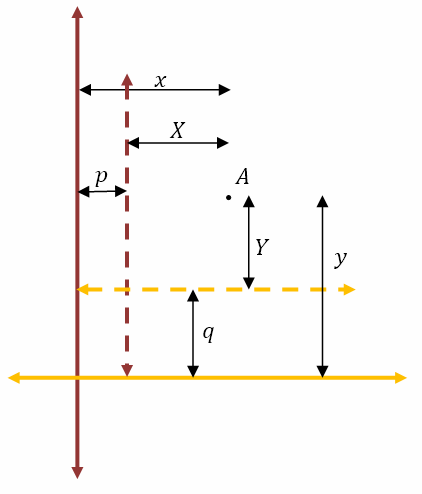

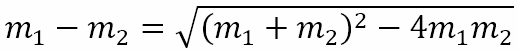

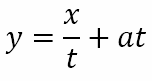

Note that, starting with A, after 5 switching sets, we have managed to alter the state of only H. This is because, 5 switching sets involves 15 switching elements, which is 1 less than 2 times 8. Hence, all the lights from A to G get switched twice, restoring them to their original state, while H gets switched only once, thereby flipping its state. In other words, if I desire to flip the state of one of the lights, all I need to do is start with its successor and perform 5 switching sets. Let us test this on an example.

Verification

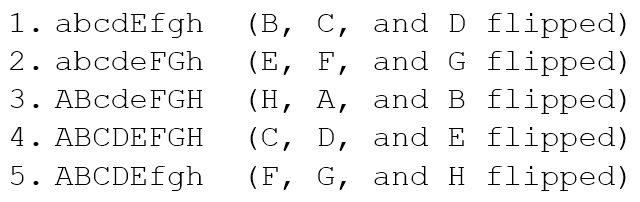

Since there are 256 (i.e. 28) different permutations of on and off lights in the set of 8, I used a random number generator to first choose a number from 1 to 256 and then iterated the random number generator that many times. The first number it spat out was 55 and I then generated 55 more numbers. This gave me 158, which in binary is 10011110. Hence, the starting case will be lights B, C, D, E, and H switched on. This is shown below.

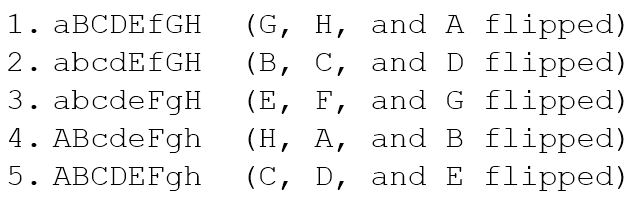

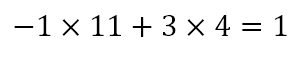

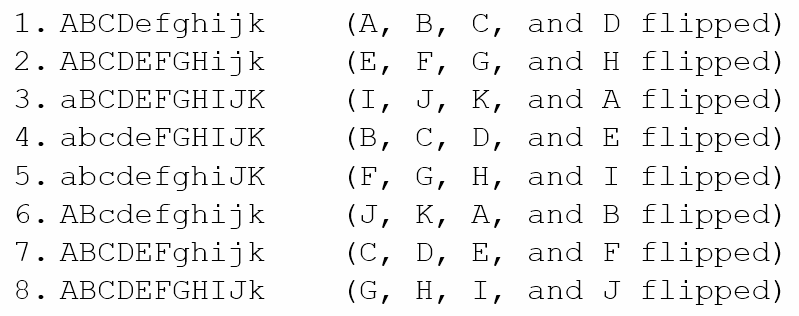

We will represent this state as aBCDEfgH, where the lower case letters indicate that the light is switched off and the upper case letters indicate it is switched on. Hence, we have to switch the lights A, F, and G on to achieve our goal. We will start with B, which is the successor of A. Performing 5 sets of switching we obtain the following states:

Note that, even though the goal was to change the state of only A, which we manage in step 5 as expected, step 4 actually gives us the final state we wanted. For now, we will ignore any occasions when the final state is accomplished in the middle and proceed only with the state after 5 sets are complete. Hence, we will continue with the state ABCDEfgh. Now F needs to be flipped. So we start with G and the next 5 sets will give us

Now, we need to flip G. So starting with H the next 5 sets give us

So, we have managed to flip light G on as well, leaving only light H off. Now, we start with A and the next 5 sets will give us

We have, therefore, achieved the final state we wanted with all lights switched on. Note, that the initial state I chose was done at random. Indeed, our algorithm indicates that, starting with any particular light, after 5 sets of switching its predecessor will be the only one to have changed states.

Bezout’s Identity

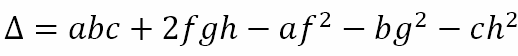

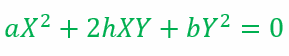

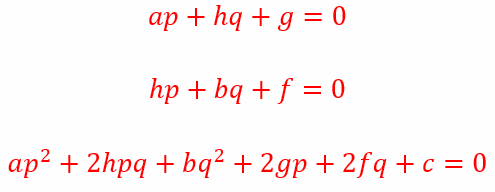

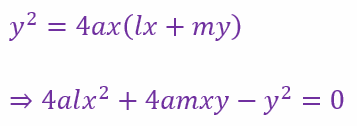

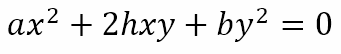

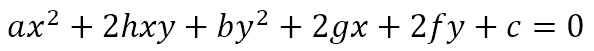

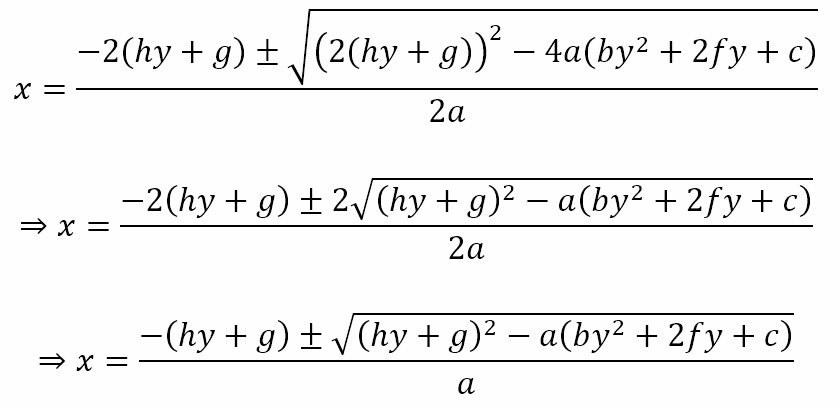

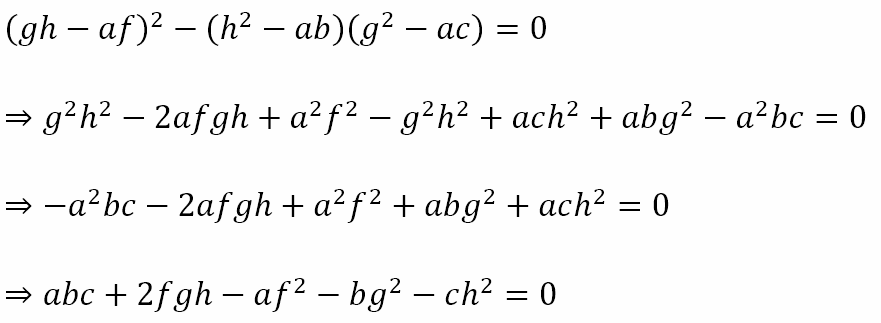

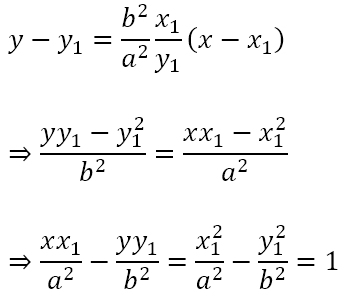

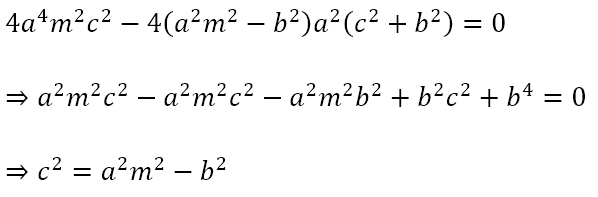

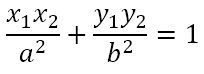

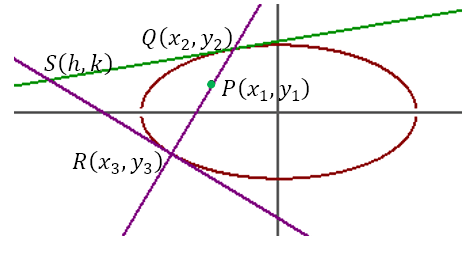

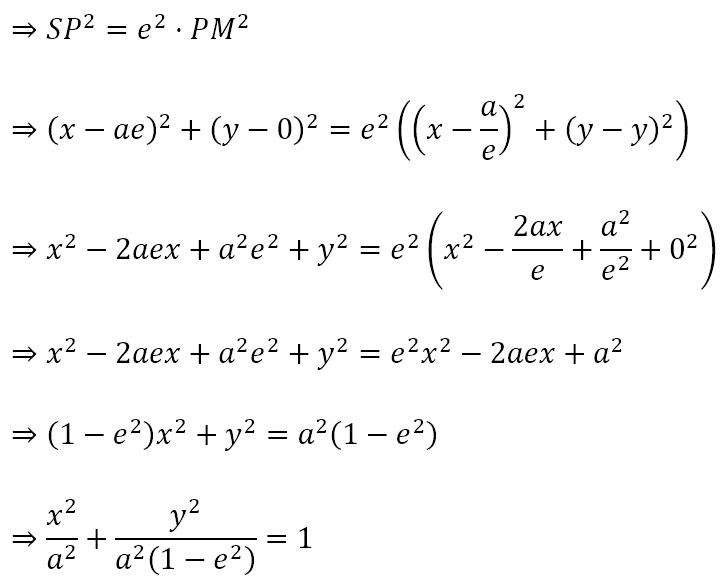

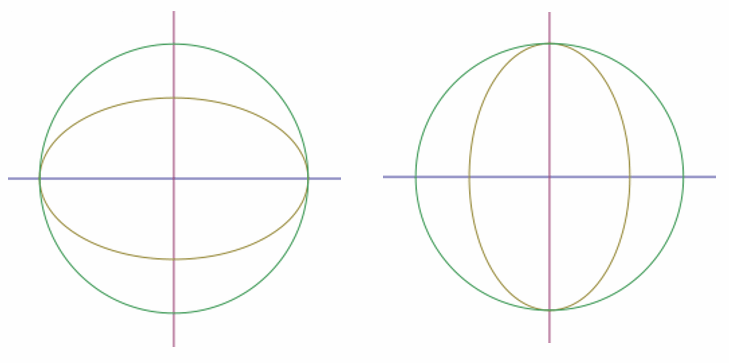

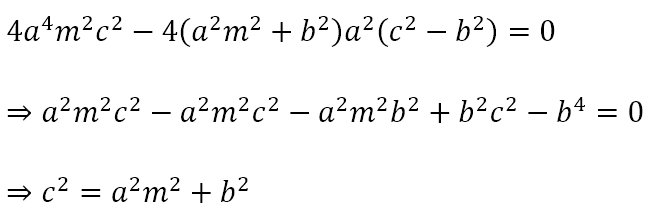

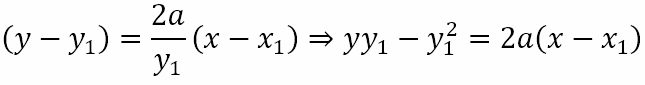

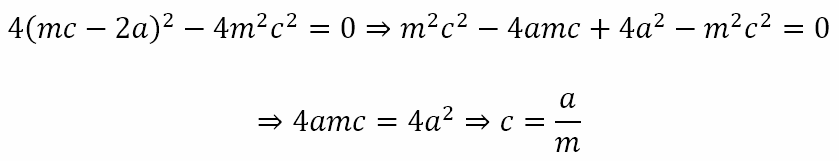

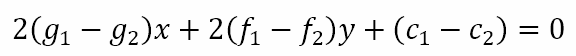

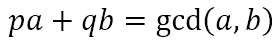

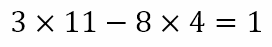

Why does this happen? Is this limited to the numbers 8 (for number of lights) and 3 (for number of consecutive lights in each set)? Of course not! Rather, what we see here is the fact that

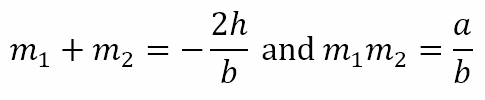

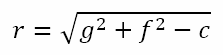

Here, the ‘2’ indicates the number of times all except one of the lights have their states changed and the ‘5’ represents the number of sets that need to be performed to isolate one light and flip only its state. Is it possible to generalize this?

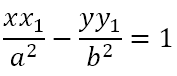

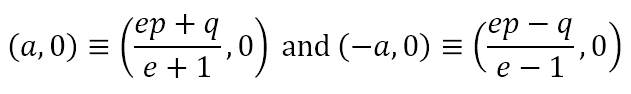

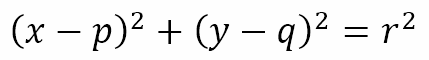

Indeed it is! This is an example of an application of what is known as Bezout’s identity. Étienne Bézout was a French mathematician who did significant work on number theory. He demonstrated that, if a and b are two natural numbers, then there exist integers p and q such that

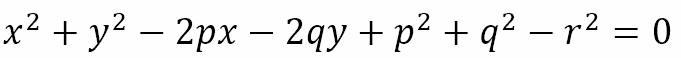

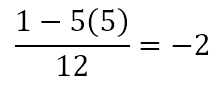

In our example, a = 8 and b = 3, for which gcd(8, 3) = 1. Here we have found p = 2 and q = -5 such that

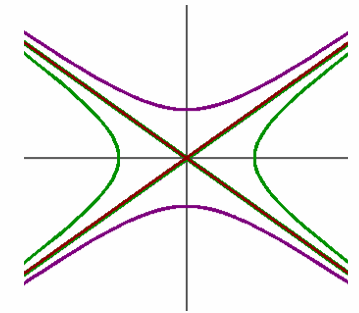

Testing a Hypothesis

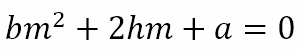

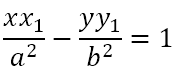

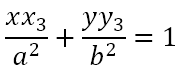

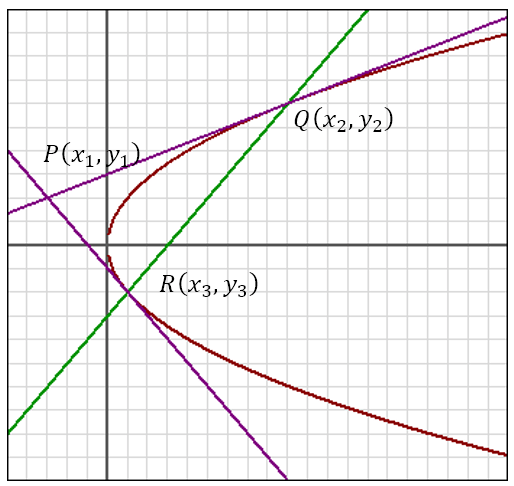

We can readily see that the reason we were able to isolate one of the lights was precisely because 5 sets of 3 each put us 1 short of a multiple of 8. Hence, can we propose that if we choose a lights and restrict ourselves to flipping sets of b consecutive lights, where gcd(a, b) = 1, then we should be able to isolate any light by conducting q set flips, which will accomplish p changes of state to all but 1 light? Let us test this hypothesis with an example.

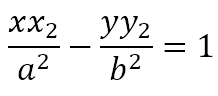

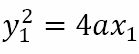

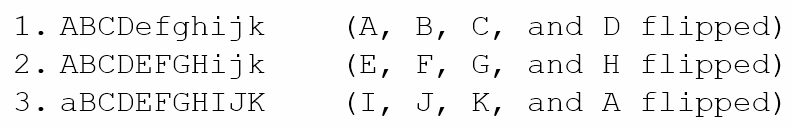

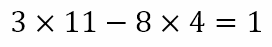

Suppose now we have 11 lights and restrict ourselves to flipping 4 consecutive lights. Let us begin with the state abcdefghijk, where all the lights are off. We observe that

Now, starting with A and performing 3 set flips, we will get

We have indeed isolated light A. However, rather than flipping the state of only A, we have managed to flip the state of all lights except A! Can we rectify this? Of course, we can! Bezout’s identity does not say that the pair (p, q) is unique. Indeed, we can observe that

This seems to indicate that we should be able to isolate A and change its state. When we perform 8 flip sets we will get the following.

Once again we observe that we have indeed isolated one of the lights, in this case K. And now too we have left it unflipped while flipping all the others. Are we stuck?

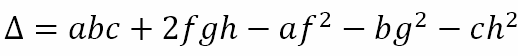

Let us try to interpret the numbers in the equation

The ’11’ and ‘4’ are clear. There are 11 lights and we are forced to flip 4 consecutive lights. The ‘8’ indicates that we will perform 8 flip sets. But the ‘3’ indicates that, when we have isolated one of the lights, all the others would have undergone ‘3’ state changes. Hence, all the lights, except the one we are focusing on actually change their states, leaving the one we are focusing on with an unchanged state. Hence, with 11 lights and flip sets of 4 consecutive lights it is not possible to isolate 1 light and change one its state. It is possible to leave only its state unchanged.

Indeed, if 11p + 4q = 1 has to hold for integers p and q then it is necessary for p to be odd. However, p indicates the number of state changes that all lights other than the one we are focusing on undergo. This means that all the other lights will change states and the one we are focusing on remains unchanged.

Modifying the Hypothesis

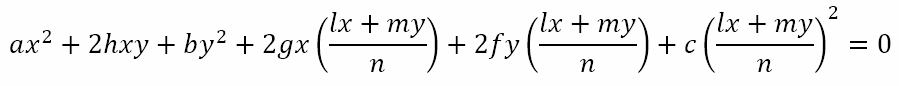

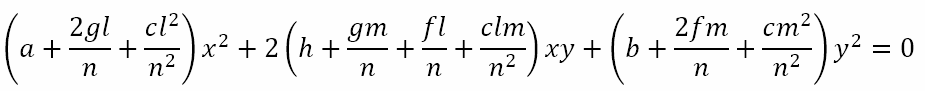

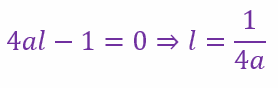

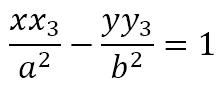

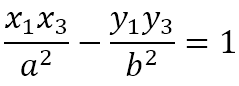

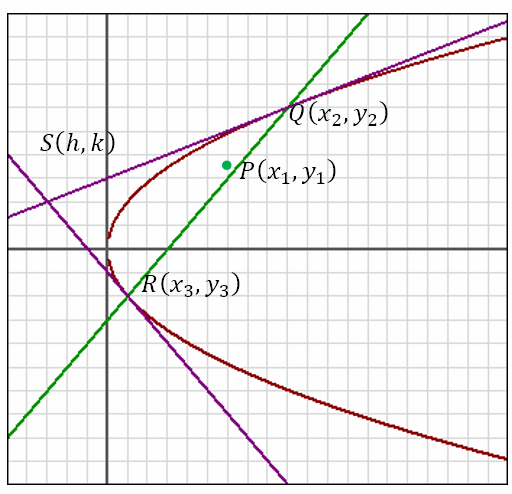

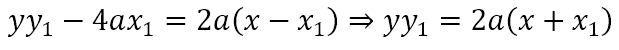

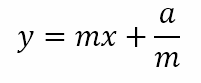

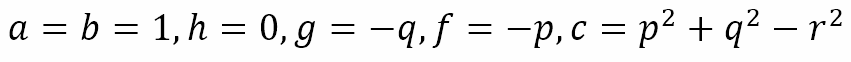

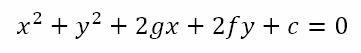

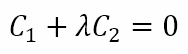

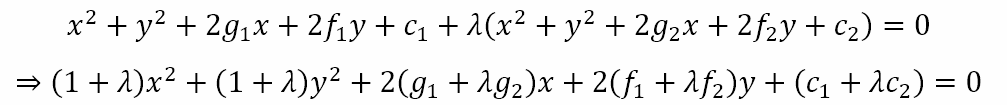

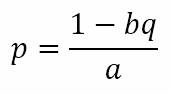

For us to be able to isolate 1 light for a state change, it is necessary but not sufficient that ap + bq = 1. In addition, p must be even so that all other lights return to their original states while the light we are focusing on changes its state. However, from ap + bq = 1 we obtain

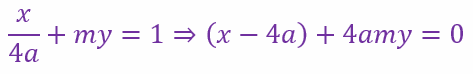

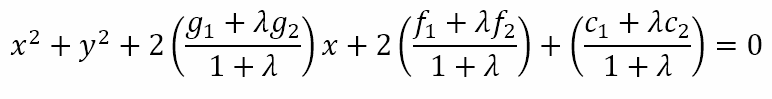

If p is even, this means that both b and q must both be odd because only then can the difference 1 – bq be even. So let’s assume that a = 12 and b = 5. The GCD of 12 and 5 is 1. Will that allow us to isolate any particular light? From the above formula, we can see that

Hence, with a = 12 lights and b = 5 being flipped each time, we should need q = 5 sets, each, except the one we start with, being flipped p = 2 times. Let’s test this starting with abcdefghijkl, the situation where all 12 lights are off. Carrying on with flip sets of 5, we can obtain the following

As can be seen, we have isolated light A and changed only its state without affecting the states of any of the others. This will allow us to change any pattern to any other pattern we desire.

Stringing Along

What we have seen is that, if the number of lights is odd, then we are not guaranteed that there is a strategy that could convert any given pattern to any other pattern. However, if the number of lights is even and the number we flip each time is coprime with the number of lights then we may be to alter any starting pattern to any other pattern. However, this is not guaranteed. Is there a way of obtaining a generalized solution to this? That is, can we determine the exact conditions for a, the number of lights, and b, the number of lights flipped each time, that will always give us the possibility of changing any starting pattern to any other pattern?