The Siege of Yodfat

In AD 67, in the middle of the first Jewish-Roman War, a rag tag band of forty Jewish revolutionaries managed to get themselves besieged in Yodfat. Realizing they were going to be captured and perhaps tortured, the group decided that they would commit mass suicide. However, given the Jewish aversion to committing suicide, none of them wanted to kill themselves. Also, some of them argued, if each person was given the responsibility of killing himself, there could be some squeamish rebels who would simply not carry through with the decision, leading to some of them losing their lives while others saved their own lives.

In order to avoid such rejection of their collective decision to kill themselves rather than being captured, they devised a plan where they cast lots and the lots told them how they were to arrange themselves. They would then arrange themselves in a circle in order of the lots. Then the first person would drive his spear through the second, killing him. Then the third person would drive his spear through the fourth, killing him. This would proceed until only one person was left and he was expected to kill himself. Hence, only the last person was expected to kill himself and end the mass suicide.

As it so happened, when thirty-eight of them had been killed, the last two decided that they would stop the killing and surrender to the Romans! One of the survivors was the Jewish historian Josephus, who narrates this story in The Wars of the Jews (Book 3, chapter 8, paragraph 7).

The Josephus Problem

This problem has come to be known as the ‘Josephus Problem’ because Josephus himself reports that he did not want to die but actually wanted to surrender to the Romans.

Hence, the problem can be framed as follows: Given forty people arranged in a circle, with each alternate person being killed by the person before him, what is the position you should be in to survive? We can generalize this as follows: Given n people arranged in a circle, with each alternate person being killed by the person before him, what is the position you should be in to survive? This involves skipping 1 person at each stage. However, the problem can be further generalized as follows: Given n people arranged in a circle, with k people being skipped and the person in position k+1 being killed by the person before him, what is the position you should be in to survive? Is there a solution to this general problem and, if so, how would we find it?

The Survivor Position

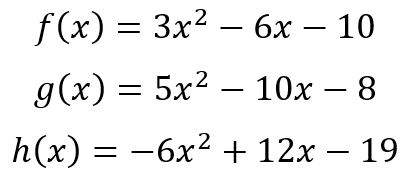

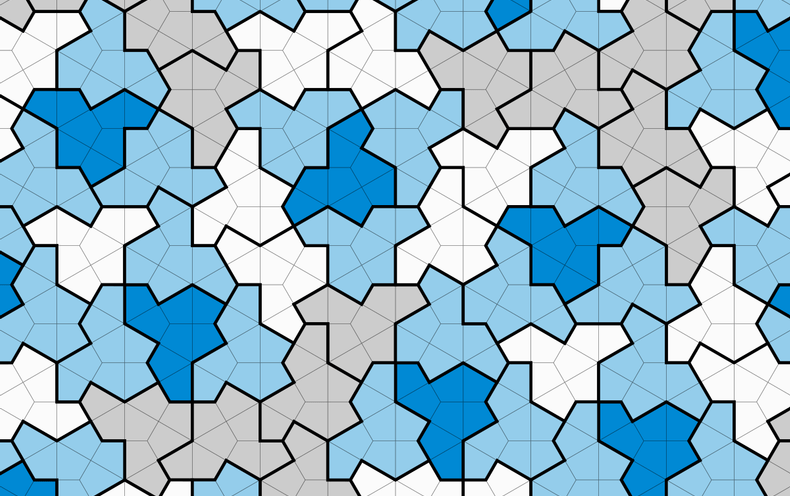

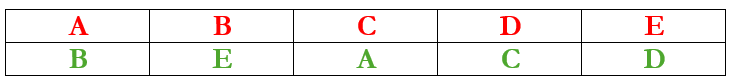

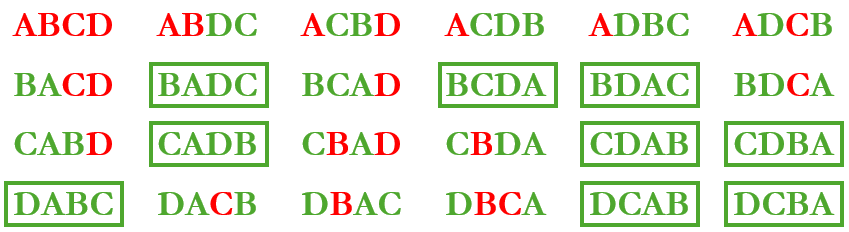

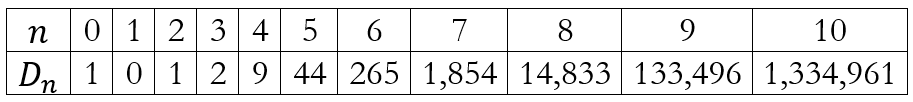

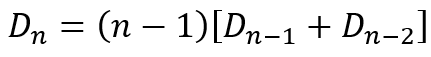

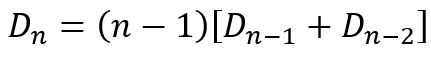

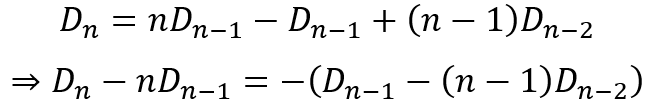

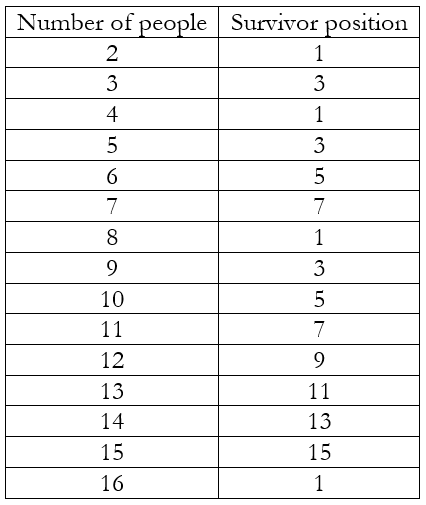

We start small! Suppose we have 3 people: A, B, and C. A kills B and C kills A. Hence, the survivor is in position 3. Suppose we have 4 people: A, B, C, and D. A kills B, C kills D, and A kills C. Hence, the survivor is in position 1. If we continue in this way we will obtain the following table

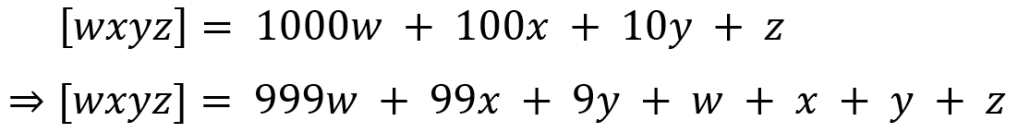

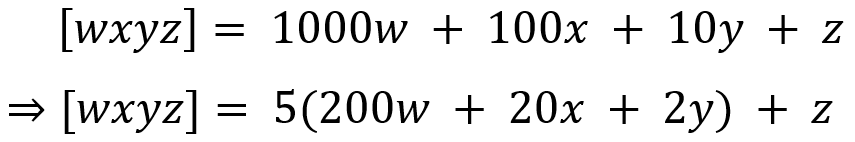

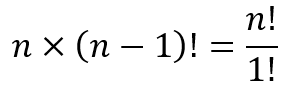

We should be able to observe some patterns here. No one in an even position is ever the survivor. This is because, when we skip just one person each time, all the even positions are killed in the first round itself. Next, whenever the number of people equals a power of 2 (i.e. 2, 4, 8, 16, etc.), the survivor is in position 1. Between two consecutive powers of 2 (i.e. 2 and 4, or 4 and 8 or 8 and 16, etc.), the survivor position proceeds according to successive odd numbers.

Hence, we can obtain the following algorithm:

- Given, the number of people (n), determine the largest power (say m) of 2 that is less than or equal to n.

- Calculate p = n – 2m + 1.

- The survivor will be in position s = 2p – 1.

Let’s test this algorithm. Say n = 13. Now 23 = 8 < 13 < 16 = 24. Hence, m = 3. This gives us p = 13 – 23 + 1 = 6. This gives, s = 2(6) – 1 = 11, which is the survivor position according to the table.

Say n = 16. Now 24 = 16. Hence, m = 4. This gives us p = 16 – 24 + 1 = 1. This gives, s = 2(1) – 1 = 1, which is the survivor position according to the table.

For the situation in which Josephus found himself n = 40. Now 25 = 32 < 40 < 64 = 26. Hence, m = 5. This gives us p = 40 – 25 + 1 = 9. This gives, s = 2(9) – 1 = 17. Hence, Josephus would have been safe if he had drawn the lot for the 17th position.

The Second Last Survivor Position

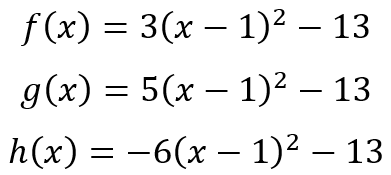

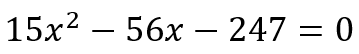

However, remember that Josephus was one of two who remained and who decided to renege on their commitment to the fallen comrades. So he need not have been the last man standing. He could have been the second last man, the one whose fate is would have been to be killed by the man in the 17th position. What position would this second last man have held? We can generate a similar table as before to obtain

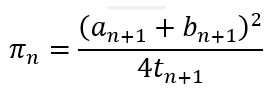

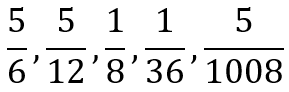

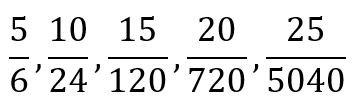

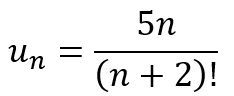

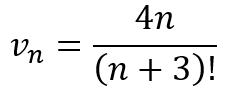

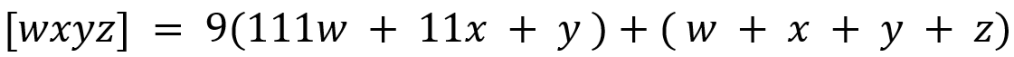

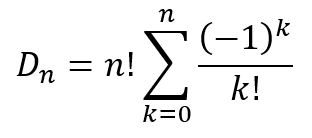

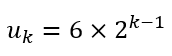

The first line is in red because of the strange case in which a person occupying an even numbered position survives. However, this is only because we are starting with 2 people. If we observe the third column, we observe once again that, apart from the anomalous ‘2’, there are only odd numbers. Further, we can see that the position resets to 1 whenever we reach 6, 12, 24, etc. This is a geometric sequence and the general term can be express as

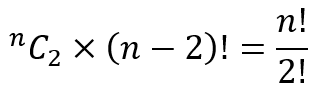

Between successive terms of this series, the third column merely goes through all the odd numbers. So we can obtain the following algorithm:

- Given, the number of people (n), determine the largest term the series uk that is less than or equal to n.

- Calculate q = n – uk + 1.

- The second last survivor will be in position t = 2q – 1.

Let’s test this algorithm. Say n = 13. Now 6×22-1 = 12 < 13 < 24 = 6×23-1. Hence, k = 2. This gives us q = 13 – 6×22-1 + 1 = 2. This gives, t = 2(2) – 1 = 3, which is the second last survivor position according to the table.

Say n = 24. Now 6×23-1 = 24. Hence, k = 3. This gives us q = 24 – 6×23-1 + 1 = 1. This gives, t = 2(1) – 1 = 1, which is the second last survivor position according to the table.

For the situation in which Josephus found himself n = 40. Now 6×23-1 = 24 < 13 < 48 = 6×24-1. Hence, k = 3. This gives us q = 40 – 6×23-1 + 1 = 17. This gives, t = 2(17) – 1 = 33. Hence, Josephus would have been the second last survivor if he had drawn the lot for the 33rd position.

Throwing Down the Gauntlet

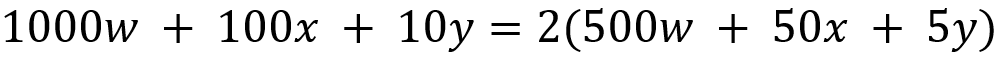

So we have now obtained positions for the last and second last survivors. However, what we have done is look at the tables and use them to obtain the ‘algorithms’ for the positions. We have not used any rigorous mathematics. What we have done is play around with the situations and keep an eye out for patterns. While there are certainly ways of deriving these ‘algorithms’, we can see that we do not need any rigorous mathematics to pull off something quite remarkable. For example, suppose we have n = 1000. Imagine, a circle of one thousand people. What would we obtain?

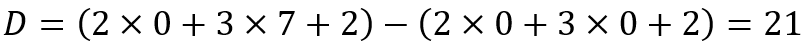

Using the first algorithm we would get: 29 = 512 < 1000 < 1024 = 210. Hence, m = 9. This gives us p = 1000 – 29 + 1 = 489. This gives, s = 2(489) – 1 = 977. Using the second algorithm we would get: 6×28-1 = 768 < 1000 < 1536 = 6×29-1. Hence, k = 8. This gives us q = 1000 – 6×28-1 + 1 = 233. This gives, t = 2(233) – 1 = 465. Hence, the last survivor is the person in position 977 and the second last survivor the one in position 465.

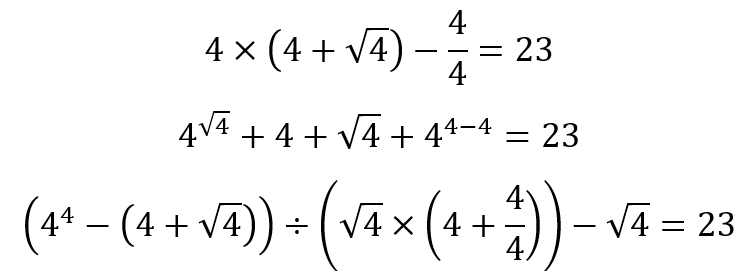

Now you know how to set up the problem and draw up the tables, can you obtain the ‘algorithms’ is we skip not one but two people each time? What kind of patterns would we see?